Summer finally set in last month with the arrival of above-normal temperatures. Much of the state was on the dry side, but thunderstorms brought locally heavy rain and even severe weather.

Summer Heat Takes Hold

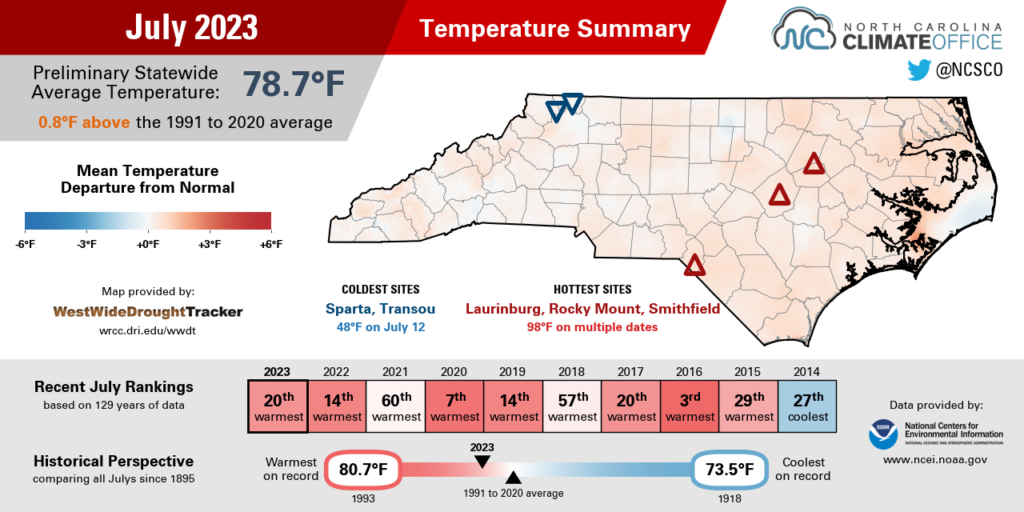

Our climatological hottest month of the year lived up to that billing, with a preliminary statewide average temperature of 78.7°F and the 20th-warmest July in North Carolina since 1895, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

The turning of the calendar to July meant an abrupt turnaround in our weather, switching from the cooler conditions of May and June to hotter and more summer-like temperatures.

Locally, Raleigh tied for its 5th-warmest July on record, Lumberton had its 6th-warmest July, and it was tied for the 9th-warmest in New Bern and Wilmington.

The Triad had yet to reach the 90-degree mark through the end of June, but Greensboro made it there five of the first seven days of July, and 14 times overall, as part of its 18th-warmest July on record. Elsewhere, it reached the 90s in Charlotte on 22 days, in Raleigh on 26 days, and in Lumberton on 28 days – tied for the third-most in any July there in its 106 years of observations.

The hottest weather hit in the final week of the month as the Bermuda high pressure system crept close to our coastline and put us under a dome of heat and humidity. For much of the state, it was the warmest weather in more than a year.

In the Mountains, Asheville climbed to 92°F on July 27, while Cullowhee had three consecutive days at 92°F from July 28 to 30. The last time they were that warm for that many days in a row was in July 2012.

Across the Piedmont, Greensboro topped out at 95°F on July 28 – its warmest day since June 22, 2022. Charlotte also reached 95°F on four different days last month, and Raleigh had back-to-back-to-back 97°F days from July 26 to 28.

The hottest spots in the east included Laurinburg, Rocky Mount, and Smithfield, which each climbed as high as 98°F, while our ECONet station at Jockeys Ridge State Park hit 97.5°F on July 28 and tied the warmest temperature recorded there since it was installed last spring.

Factoring in the humidity, heat index values rose as high as 115°F along the Albemarle Sound in Edenton on Friday, July 28. And the wet bulb globe temperature – a measure of heat stress experienced in direct sunlight – hit extreme levels across the Triangle on July 27.

We weren’t the only ones dealing with heat and its impacts last month. Globally, July was set to finish as the hottest month on record since 1940, with record-breaking heat waves in China, Europe, and the southwestern United States.

This isn’t a fleeting phenomenon, either. The North Carolina Climate Science Report notes that our heat index values are very likely to continue increasing due to both warming temperatures and higher absolute humidity levels caused by climate change.

Dry Areas Emerge Amid Storm-Soaked Spots

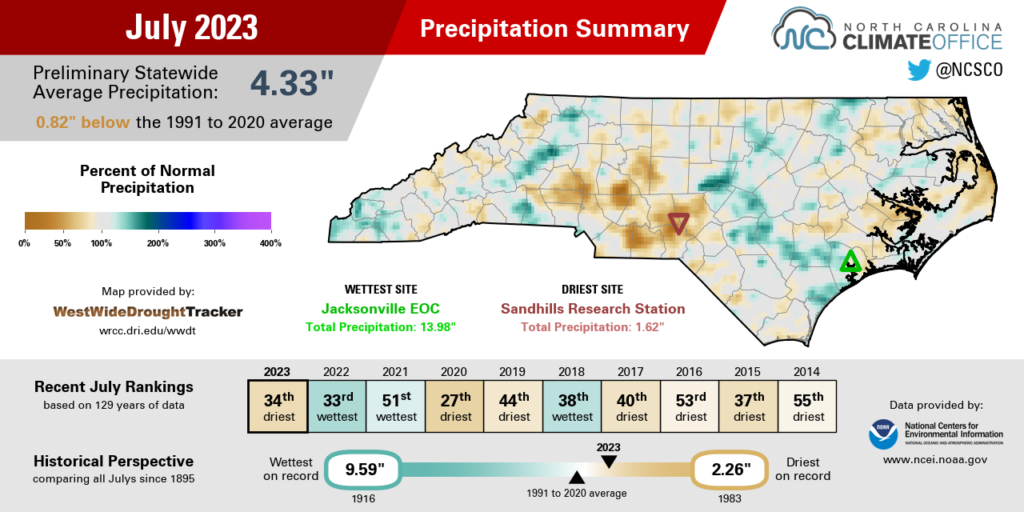

While some places were drenched by slow-moving summer storms, that heavy rain wasn’t widespread, making it a drier month across much of the state. Per NCEI, the preliminary statewide average precipitation was 4.33 inches, which ranks as the 34th-driest July in the past 129 years.

One round of soaking showers affected northern Wake County on July 13-14. More than five inches of rain caused flooding on greenways and at the Holding Park Aquatic Center in Wake Forest.

The following weekend, a cold front pushing through on July 15-16 dropped 4 to 5 inches of rain over Caldwell County. In nearby Alexander County, flash flooding carried away two people, drowning one while the other was rescued.

And on July 19-20, locally heavy showers totaling more than 5 inches at the southern coast caused roadway flooding in Pender County.

In between those wet spots, though, it was generally dry, especially for much of the Piedmont. Greensboro was more than an inch below normal in its 33rd-driest July since 1903, and our ECONet station in Jackson Springs reported just 1.62 inches of rain all month, which was 3.47 inches below average and its 2nd-driest July in the past 21 years, behind only 2006.

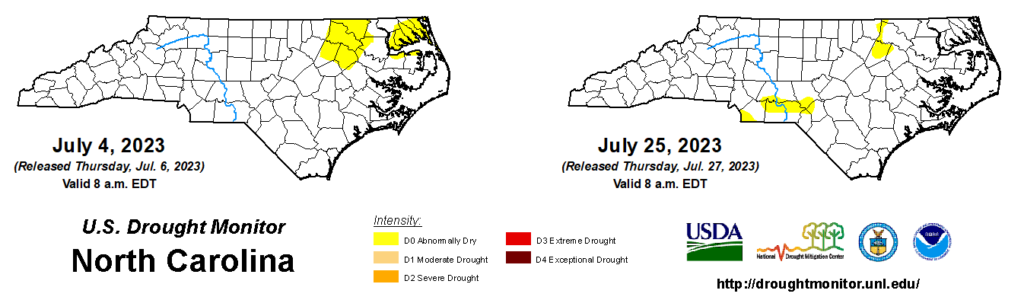

That lack of rainfall, combined with the warmer temperatures and accelerated evaporation rates, led to the expansion of Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions across parts of the southern Piedmont by the end of the month. Streamflows in the Sandhills have fallen below the historical 10th percentile for this time of year, including flows in the 2nd percentile on Drowning Creek and the lowest levels there since July 2018.

Thanks to the heavy rain in late June, reservoirs generally remain near their seasonal target levels, so there are no imminent concerns about water supplies. For now, the main impacts you’re likely to notice are yellowing lawns, trees dropping leaves to conserve moisture, and the ground becoming hard and cracked as soil moisture evaporates.

That’s typical of summertime dryness, but if these hot and dry days stack up in August, then we could see the return of drought in parts of North Carolina for the first time since late April.

Severe Weather Includes a July EF3

Despite the warmer temperatures last month, one aspect of our weather remained decidedly spring-like: intense thunderstorms, capped off by a first for July in North Carolina.

The month started with action in the northeast, including an EF0 tornado in Bertie County on July 3. Per the National Weather Service’s storm survey, the tornado destroyed one building and tore the roof off another during its half-mile track that afternoon.

The following day, fireworks weren’t the only light show in the sky on July 4. Afternoon thunderstorms produced lightning strikes that caused house fires in Camden and Pasquotank counties.

On July 7, storms dropped half dollar-sized hail and blew down trees in Wake and Wayne counties. Two days later, there were even more widespread gusty winds, downed trees, and power outages on July 9.

The strongest storms of the month moved through on July 19. Warm, humid air was in place across eastern North Carolina that day, offering plenty of instability to initiate and strengthen developing thunderstorms. One measure of that instability is the Convective Available Potential Energy, which was greater than 3,000 Joules per kilogram over the Coastal Plain, representing support for potent updrafts.

The other key ingredient was a mesoscale convective vortex, or a remnant mid-level low pressure system, tracking into North Carolina from the west, where it had a history of producing strong winds and even a tornado in northern Alabama.

That system brought along increased helicity levels, and when combined with those updrafts to tilt the spiraling air vertically, the resulting conditions supported tornado formation for a brief window in the afternoon.

Around 12:25 pm, a tornado touched down near Interstate 95 in Dortches, then reached EF3 strength – with peak winds estimated at 140 to 150 mph – as it crossed into Edgecombe County.

During its 16.5-mile track, it damaged or destroyed an estimated 89 structures in Nash County, and others including a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant in Edgecombe County.

In the Storm Prediction Center’s tornado records dating back to 1950, this is the first tornado classified at the F3/EF3 level or stronger to occur in North Carolina in the month of July. (Their archives do show an F3 tornado on July 4, 1967, that touched down along the North Carolina/Virginia border. However, the official records list it as a Virginia-only event.)

It’s also only the third tornado of that strength to occur during our climatological summer, from June through August. On August 29, 1964, an F3 tornado tracked from east to west across Scotland and Richmond counties, and on August 3, 2020, an EF3 spawned by Hurricane Isaias caused two deaths in Bertie County.

While that sort of severe weather is unexpected this time of year, as last month showed, it is possible under the right conditions, no matter what the calendar says or how warm or cool a season has started.