With year-long temperature and precipitation records on the line, we narrowly missed both following warm and wet (but not warm and wet enough) weather in December. The initial stats still show it was an extreme year. You’re invited to learn more in an upcoming webinar!

Cooler Spells Temper our Temperatures

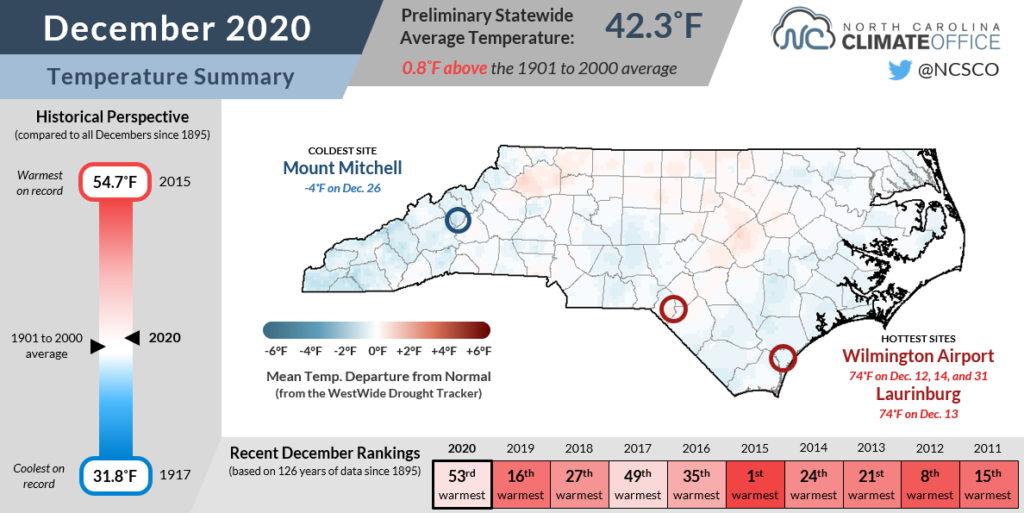

While a moderately warm month could have set a new annual temperature record for the state, December instead stumbled across the finish line with average temperatures less than a degree above the long-term average.

The National Centers for Environmental Information reports a preliminary statewide average temperature of 42.3°F, which was our 53rd-warmest December out of the past 126 years. It did continue a string of ten consecutive Decembers with above-normal average temperatures in North Carolina.

Our average high and low temperatures for the month were generally within a degree or two of normal. Along the Outer Banks, Ocracoke was a few degrees above normal. In the Mountains, some sites were slightly below normal, including Hot Springs, which had its 10th-coolest December since 1986 and its coolest since 2005.

The month featured a mix of warm and cool periods, but we began on the cool side following a cold frontal passage on December 1 that dropped our highs into the 40s.

Temperatures steadily climbed through the middle of the month as high pressure built in off the coast and ushered in warmer air from the south and highs in the 60s.

Another high pressure system to our north wedged cooler air against the Appalachians and began a string of foggy nights and chilly days from December 16 to 20.

The month ended in a final fling with warm weather as high temperatures reached the 70s along the coast on New Year’s Eve.

Overall, we had more warm than cool days last month, but it was a far cry from the persistent warmth in December 2019 that helped us wrap up that record-setting year — and we needed a similarly warm December in 2020 to take the annual temperature title.

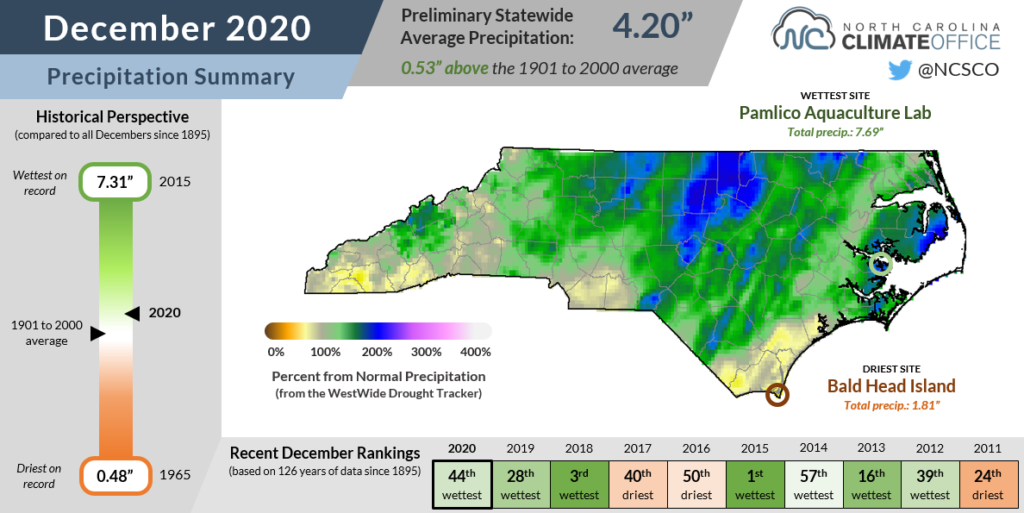

Cold Fronts Bring Rain and Some Christmas Snow

The statewide annual precipitation record was also in reach entering December, but it would have taken one of our wettest Decembers ever to get there. In the end, it was a wet December, but not to that record effect. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 4.20 inches, or our 44th-wettest December since 1895.

The regular cold frontal passages that kept our temperatures in check also brought rain across the state. The heaviest precipitation fell across the northeastern Piedmont and the central Coastal Plain.

Louisburg had 6.43 inches for its 5th-wettest December out of 118 years with observations. In Elizabeth City, it was the 4th-wettest December since 1934 with 6.25 inches total. And our Aurora ECONet station at the Pamlico Aquaculture Field Lab recorded its wettest December out of the past 21 years, with a 7.69-inch sum topping the December 2018 total of 7.16 inches.

Up to 2 inches of rain fell on Christmas Eve, and while it was just a wet Christmas in most areas, some lingering moisture behind a cold front fell in the form of snow, giving a rare white Christmas in western North Carolina.

Six inches fell at Beech Mountain, Marshall, and Oconaluftee, while Boone picked up 2.5 inches of snow and the Asheville area had 1 to 2 inches. A few flakes fell across parts of the Piedmont on Christmas Day for the first time since 2010.

Some areas across the southern Coastal Plain and southern Mountains didn’t receive as much rain — or snow — during December, and they finished the month slightly drier than normal. With 2.66 inches, Wilmington was an inch below normal for December, but it was still the 3rd-wettest calendar year on record there.

In the far western corner of the state, Murphy was 1.3 inches below normal for December, but more than a foot of precipitation above normal in 2020 with 70.0 inches total. That ranked as its 6th-wettest year since 1968.

An Extreme Year, Statewide and Locally

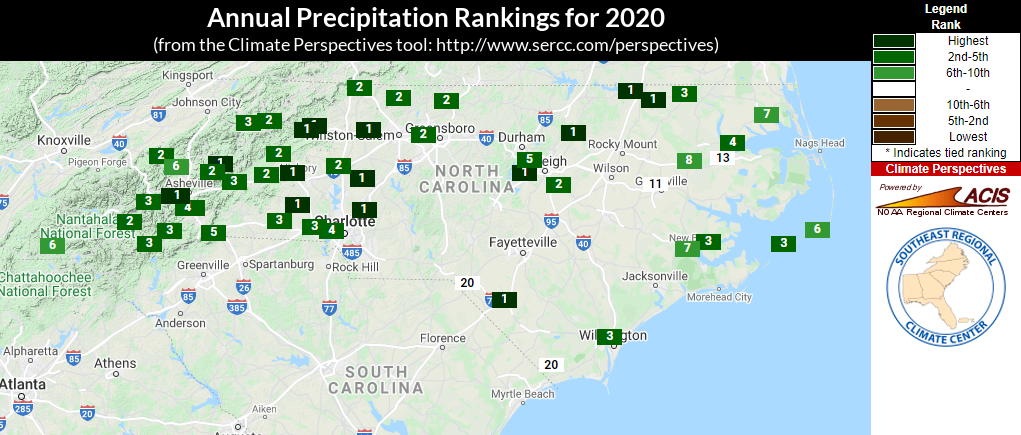

While 2020 wasn’t a record-setting year for temperatures or precipitation on a state level, it was still exceptionally warm and wet overall. The preliminary statistics from NCEI show 2020 ranked as our 4th-warmest and 2nd-wettest year out of the 126 years with observations available.

The statewide average temperature of 60.95°F was 0.38 inches behind the record from 2019, and the average precipitation of 66.00 inches was 2.35 inches short of the tally from 2018. (Note that these numbers and rankings could change slightly — but not enough to secure either record — once the final December data is processed by NCEI later this week.)

Being so close to both records is still an impressive feat, and by that measure, 2020 could be considered one of our most extreme years weather-wise. Dating back to 1895, 2020 is the only year with both the annual temperature and precipitation rankings among the top five highest or lowest in North Carolina.

Only four years, including 2020, have had both the annual average temperatures and precipitation ranked in the top ten; the others were 2015 (9th-warmest and 10th-wettest), 2007 (10th-warmest and 1st-driest), and 1901 (7th-coolest and 4th-wettest).

Locally, some individual weather stations did set new annual records in 2020. Hatteras had its warmest year on record, with the average temperature of 66.8°F exceeding the mark of 66.3°F set in both 2017 and 2019. Greenville tied 2019 for its warmest year on record with an average temperature of 64.0°F.

A number of sites especially in western North Carolina had their wettest year on record, including Concord, North Wilkesboro, and Yadkinville. In Hickory, the race for the record wasn’t even close; the 80.64 inches measured at the airport in 2020 easily bested the previous record of 66.87 inches, set in 2012.

If you’d like more information about the past year in North Carolina’s weather, we invite you to join us for our Year in Review Webinar next Monday, January 11 at 11 am. In this hour-long virtual presentation, we’ll discuss the hazards and weather events we endured, statistics from across the state, and where this year fits with long-term trends in our climate.

You can register for the webinar at this link. Registration is free but required in advance, and the webinar is open to everyone.

If you can’t attend, we’ll record the webinar and post it afterwards, and we will also summarize the key points in a year-in-review blog post next week. Until then, we’ll keep crunching the numbers about the extreme year of 2020 in North Carolina.