Less than a month removed from Florence, North Carolina has now weathered another hit from a hurricane. This time, though, it was the Piedmont — not the coast — that bore the brunt of the damage in our state.

In Florence’s case, we noted that it had few equals in our hurricane history because of its slow-moving track that produced record-setting rain and flooding. It’s also tough to find a close match for Michael, but for a slightly different reason.

Climatologically speaking, tropical storms that make landfall along the Gulf coast are much more likely to move over the North Carolina Mountains — such as Frances and Ivan in 2004 — than the Piedmont.

The last hurricane to make landfall along the Gulf coast and still be at tropical storm-strength when its center reached the North Carolina Piedmont was the 1935 Labor Day hurricane. Prior to that, the next such storm was the 1896 Cedar Keys hurricane, which had mostly limited impacts across the then-rural Piedmont, but knocked out trees and power in Raleigh and Durham, causing at least one death.

Michael thankfully spared the already hard-hit Carolina coast from another blow, but in parts of the Piedmont, the impacts from this storm — particularly from high winds — were worse than those in Florence.

Wind Damage

Even though Michael made landfall more than 400 miles from our state, it had less than 24 hours to scrub off its Category-4 intensity, which kept it plenty potent by the time it arrived here.

While Michael’s surface winds were dampened by friction as it moved over land, wind speeds of more than 50 knots (57 mph) remained less than a mile above the ground, and downward-rushing air accompanied by heavy rain within the storm helped bring some of these strong winds to the surface.

Although we often describe the right front quadrant of a hurricane as the most damaging since its forward speed adds to the wind speeds, in Michael’s case, a cold front just to the west of the storm meant a stronger pressure gradient — and therefore stronger winds — on its left or western side.

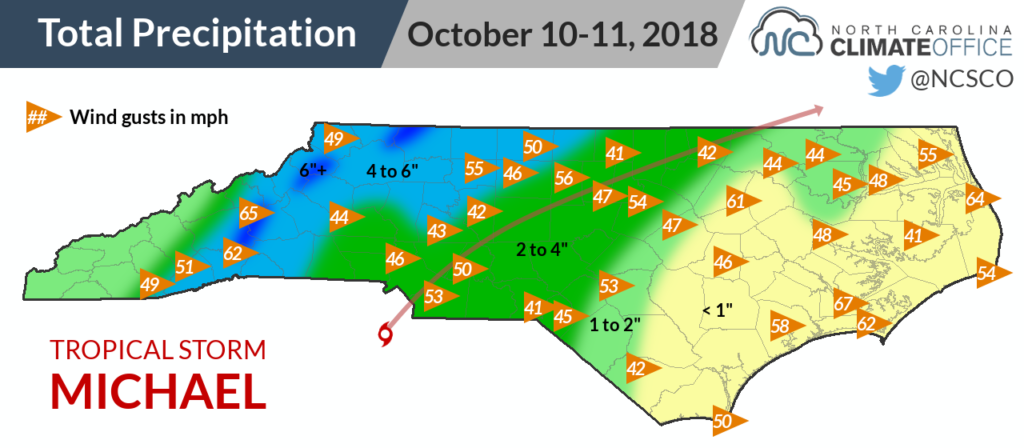

While the peak gusts were felt on either side of the state — 67 mph at the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station in Craven County and 65 mph atop Mount Mitchell — the northern Piedmont also experienced some strong gusts, including 55 mph in Winston-Salem, 56 mph in Burlington, and 54 mph at the Raleigh-Durham Airport.

Those high winds resulted in widespread downed trees that fell across roads, structures, and power lines. NC Emergency Management reported nearly 500,000 customers without power across the state.

For much of the western Piedmont, the winds and resulting damage were the worst from a tropical system in more than 29 years. In September 1989, Hurricane Hugo also made landfall as a Category 4 and retained its strength hundreds of miles inland, toppling trees and knocking out power to 690,000 Carolina Power & Light customers.

Rainfall

With very strong winds on the back side of the storm, the rain that fell ahead of it saturated the ground and made trees even more likely to fall when a strong gust blew through.

Rainfall totals generally ranged from less than an inch in the eastern part of the state to around 5 inches in the Triad — which resulted in the need for water rescues in some areas — and more than six inches at some high-elevation sites in the Mountains. As it often does when clouds form while rising up its slopes, Mount Mitchell reported the maximum two-day precipitation total of 8.58 inches during this event.

That rainfall has already sent the Haw and Yadkin rivers into minor flood stage, and the Dan River near Danville, VA, crested at a record-setting level in its major flood stage. As that water heads downstream, it could result in minor flooding particularly along the Pee Dee and Cape Fear rivers closer to the coast in the same areas that were inundated by Florence.

With its unique path to our state and the impacts it brought along, Michael is sure to be a memorable storm for many, likely standing next to — instead of as a footnote beneath — Florence in the history books. For those who suffered damage from it, to quote a jingle from the 1990s, they won’t want any future storms to be like Mike.