The oceans, they are a changin’. The El Niño conditions that were so prominent in the Pacific Ocean just five months ago have now nearly vanished, and the current neutral ENSO conditions and expected La Niña event largely shape this year’s summer and tropical outlook.

ENSO Update

Sea surface temperature anomalies in the central equatorial Pacific were more than 2°C above normal through most of last winter as part of one of the strongest — and by some indicators, the strongest — El Niño event on record.

By late February, cooler water moving from west to east beneath the Pacific Ocean’s surface caused that warm pool to begin fading in intensity. Over the past month, below-normal temperature anomalies emerged at the sea surface, effectively ending the year-long El Niño event.

Current sea surface temperature anomalies in the central Pacific are near zero, meaning that we’re in neutral ENSO conditions. That might not last for long, though, as cooler water should continue building in the Pacific this summer.

Longer-term ENSO forecasts are often shrouded in uncertainty this time of year since conditions tend to evolve quite a bit during the summer. However, forecasters are feeling fairly confident that we’re on our way to a La Niña pattern.

The majority of climate model forecasts show La Niña conditions — temperature anomalies of 0.5°C or cooler — emerging by the late fall. Forecasters at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute at Columbia University have even more confidence, giving about a 75% chance of a La Niña event this fall and next winter.

Hurricane Season Outlook

An emerging La Niña is one factor that could make this year’s Atlantic hurricane season an active one. In fact, the season is already off to a quick start. While the three named storms — January’s Alex, May’s Bonnie, and this month’s Colin — are not La Niña-related, this is the earliest formation on record of the season’s third tropical storm.

As the summer continues, conditions in the tropical Atlantic should be favorable for additional storm development. While El Niño caused higher wind shear across the Atlantic basin that tore apart developing storms last year, shear should be lighter as El Niño’s atmospheric impacts fade away this summer. In addition, sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic are warmer than normal at the moment — a sharp contrast to last year’s cooler waters that helped inhibit storm formation.

With these factors in mind, forecast teams on both sides of the Atlantic have run their model simulations and generated predictions for the 2016 tropical season:

| # of named storms (including Alex & Bonnie) | # of hurricanes | # of major hurricanes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term avg. (1950-2013) | 10.8 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| NC State (issued Apr. 15th) | 15 to 18 | 8 to 11 | 3 to 5 |

| UK Met Office (issued May 12th) | 15 | 9 | (no prediction) |

| TropicalStormRisk.com (issued May 27th) | 17 | 9 | 4 |

| NOAA (issued May 27th) | 10 to 16 | 4 to 8 | 1 to 4 |

| Colorado State (issued June 1st) | 14 | 6 | 2 |

These forecasts generally show near- to above-normal activity. The prediction from NC State University researchers calls for up to 18 named storms, which would rival the total from the active 2011 season that was also fueled partially by an emerging La Niña.

As with any hurricane season, it’s worth remembering that regardless of how many or how few storms occur, any storm can have major local impacts. In fact, the Outer Banks of North Carolina has already seen an impact from one of this season’s early blooming storms. Tropical Storm Bonnie and its remnants brought 14.35 inches of rain to Hatteras in a one-week period. That ranks as the second-wettest unique 7-day period on record at that site, edged out by a wet week in November 1985 when 15.86 inches fell.

North Carolina’s Summer Outlook

Long-range summer forecasts are notoriously challenging for several reasons. In the winter, most of our predictions are based on the jet stream’s likely strength and position. However, the northerly jet stream is weaker in the summer, so it doesn’t have as much of an effect on our weather. Also, most of our summertime precipitation comes from localized thunderstorms for which there is little advanced predictability, instead of from large-scale cold fronts and low pressure systems.

ENSO also has limited effects on us this time of the year, so in essence, the current neutral conditions open the door to a range of possible summertime weather in North Carolina. Two recent ENSO-neutral summers, for example, saw vastly different conditions: we were warm and dry in 2007, but cool and wet in 2013.

The Climate Prediction Center’s seasonal forecasts reflect this lack of predictability, particularly in its precipitation forecast, which shows equal chances of above-normal or below-normal precipitation for the southeast US. The CPC does predict above-normal temperatures for much of the US, aside from parts of the central Plains where the trend of recent rains is expected to continue.

That forecast of possible warmer-than-normal summer weather can rightfully invite concerns about drought. One of our worst droughts on record began in the summer of 2007, which was sandwiched between an El Niño winter and a La Niña winter.

However, that’s certainly no guarantee that we’ll see the same thing this summer.

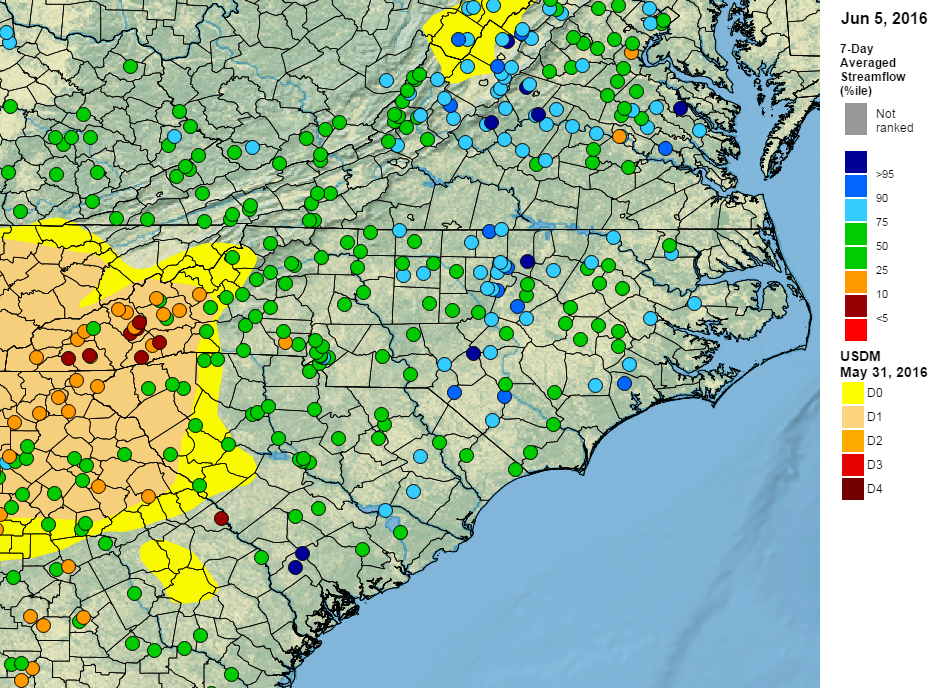

Although the western half of the mountains remains in Moderate Drought conditions, the rest of the state has been relatively wet over the past month, so streamflow (left) and reservoir levels are near normal entering the summer.

Even in drought-affected parts of the mountains, where year-to-date precipitation deficits exceed 7 inches in some spots, actual drought impacts to agriculture have been limited this spring.

A month or two of hot, dry weather could still cause drought to arise in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of North Carolina as we saw last June. But as the summer begins, a widespread drought in North Carolina is not an imminent threat.