This post is part of a series highlighting the summer projects from our office’s student research assistants. The author, Aurelia Baca, is completing her Master’s degree in Climate Change and Society at NC State University.

Forests are a valuable part of the biosphere, providing clean water, recreation areas, wildlife habitat, and carbon storage, along with uses for timber and paper production. Particularly, the Loblolly Pine trees are native to the Southeastern US, and they grow relatively quickly and have no major long-term health issues. With the many uses of this tree, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) funded the five-year PINEMAP project to investigate Loblolly Pine production in the past, present, and future.

Like every other living organism, the Loblolly Pine faces some environmental hazards. The most destructive pest is the southern pine beetle (SPB), estimated to have caused over one billion dollars in damage between 1992 and 2002. Also, below-freezing temperatures often damage Loblolly seedlings causing fewer trees to grow and mature. So, for my project, I compared the historical annual number of below-freezing days with SPB outbreaks to examine the relationship between these risks, and I looked at future projections of below-freezing days to determine how the risk factor may change in the future.

For this study, the SPB outbreak data was obtained from the USDA, with county-based data available from 1960 to 2004. The annual number of days below-freezing were computred from the Multivariate Adaptive Constructed Analogs (MACA) data, which contains downscaled output from 20 global climate models. Each model includes a simulation of the historical period from 1950 to 2005. By comparing the MACA data with observed gridded observations from the historical Idaho dataset, I was able to determine the bias in the models across the Southeastern US. Also, to study possible future changes in below-freezing days, I used MACA projections from 2020 to 2099, including two different future pathways (moderate and intense warming).

A correlation test between SPB outbreaks and annual number of freezing days yielded surprising results which essentially indicated no relationship between the two. The weak relationship could be due to one of the variables used. The mean number of days below freezing does not indicate specifically how cold the temperatures were (instead, only that they were below 32°F), and extreme cold values much lower than 32°F are known to affect SPB populations.

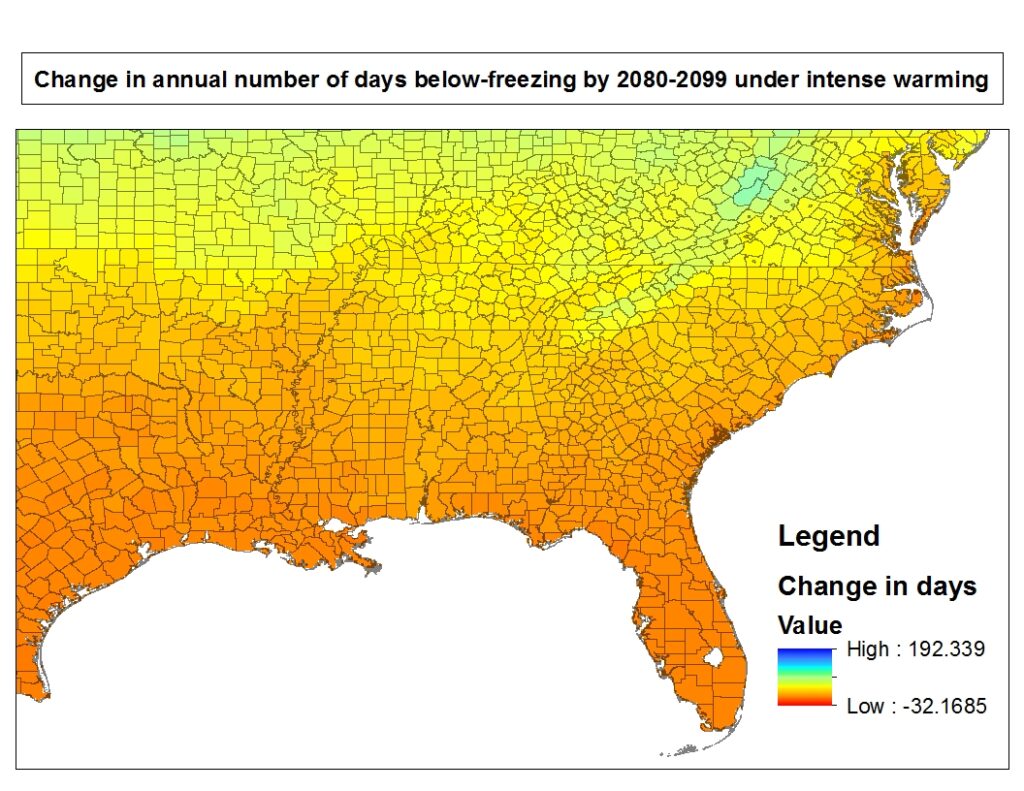

Both future pathways indicate a decrease in the annual number of freezing days by 2099, as shown by an example on the left. For instance, the mean historical annual amount of freezing days in Eastern North Carolina is 65 days. The moderate warming pathway projected the freezing days to decrease 25 days by 2099. Meanwhile, the intense warming pathway projected a decrease of 40 days by 2099. This projected decrease could lead to reduced risk of Loblolly Pine tree mortality and thus more growth of these trees and carbon sequestration.

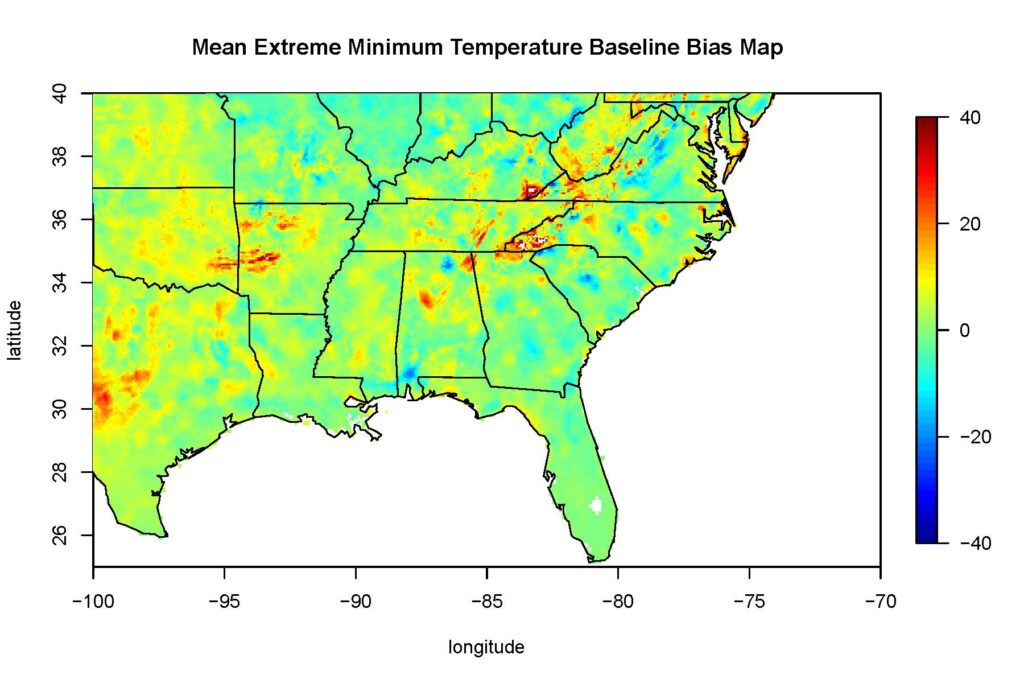

A statistical bias is present in the modeled average annual number of days below-freezing, as shown below. In fact, all 20 climate models slightly differed from the observed historical dataset, but some of the largest differences occurred in the Appalachian Mountains. The models generally over-predicted the amount of freezing days over the Appalachian Mountains. Therefore, there is less confidence in the two future pathways over the mountain range. However, the natural extent of the Loblolly Pine does not inhabit this region.

As mentioned above, the correlation test revealed no relationship between SPB outbreaks and freezing days. So, for future work, it would be interesting to study the relationship between minimum winter temperatures and SPB outbreaks as well as other climate variables (i.e. precipitation).

Overall, in terms on the bias analysis, most of the models predicted the annual number of days below freezing with reasonable accuracy over the Southeast. The results from these analyses could provide useful information for the Forest Service and local forest managers as they seek to grow more Loblolly Pine and help us all reap their benefits, whether it’s cleaner air and water or a nice place to go exploring.