This time of year, our thoughts often turn to the ocean. It’s a great place for a vacation, and often a welcome relief from stress and heat. As climatologists, we also think about the oceans — Atlantic and Pacific — because they can give us some clues about how our summer weather and hurricane season might play out.

El Niño Update

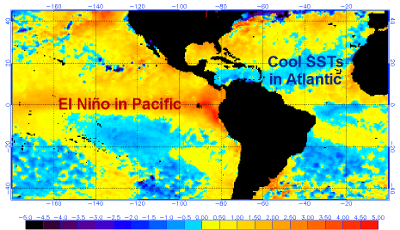

During the spring, warming at the ocean surface in the equatorial Pacific meant the emerging El Niño became even stronger. Since our last update in late March, the El Niño pattern has also taken on a more typical look, with above-normal sea surface temperatures building farther east, including a warm wedge just off the South American coast.

For the summer months, 93% of the ENSO forecast models predict a continuing El Niño event, although at varying levels of intensity. About 79% of the models also show El Niño conditions sticking around through next winter, but some suggest it may be weakening by then.

That could be an interesting consequence of this year’s El Niño developing during the late winter rather than the spring. As NOAA noted in its latest ENSO Blog post, only once in the past 60 years — in 1986-87 — has an El Niño event emerged in the winter and stuck around until the following winter. If this year’s pattern persists through the summer, that may be a telling sign as to whether it’ll also be there next winter.

North Carolina’s Summer Outlook

As we often mention, El Niño’s impacts to North Carolina’s weather are generally strongest in the winter and weakest in summer. That’s because the summertime jet stream is weaker and most of our rainfall comes from localized thunderstorm activity, rather than the large-scale lows or frontal passages that can be affected by the El Niño pattern.

Instead, we often look at climate model forecasts such as the CFSv2 (Coupled Forecast System version 2). However, the latest CFS forecast shows little strong guidance for summertime temperature or precipitation anomalies across North Carolina. It’s worth noting that this model ensemble, like most, is sensitive to the initial conditions. So given the recent rains across the Midwest, it’s no surprise that the model forecast shows cool, wet conditions for that region over the summer.

Our recent weather, which has been warm and dry in May, also provides few clues about what summer may hold. Past research at our office shows essentially no correlation between springtime and summertime temperatures in North Carolina.

With the challenge of summarizing this guidance — or lack thereof — in its three-month outlooks, the Climate Prediction Center predicts a slight likelihood of above-normal temperatures for eastern North Carolina this summer with an equal chance of above-, below-, or near-normal precipitation.

Hurricane Season Outlook

The Atlantic hurricane season officially begins next Monday, June 1, but the season got off to an early start when Tropical Storm Ana formed earlier this month and moved ashore along the Carolina coast. Is this tropical activity in May a sign of things to come for the rest of the summer?

Probably not, at least according to the pre-season forecasts, which account for a variety of environmental predictors of tropical activity. This year’s forecasts are being driven primarily by the El Niño event in the Pacific. It’s expected to strengthen trade winds and increase wind shear across the Atlantic, which can make it tough for storms to develop.

Slightly below-normal sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic, from the coast of Africa through the Caribbean, may also inhibit storm formation across that main development region.

If these factors sound familiar, it’s because similar conditions were in place last year, which had below-average tropical activity. This year’s forecasts generally predict similar or slightly less activity than we saw in 2014:

| Source | # of named storms (not including Ana) | # of hurricanes | # of major hurricanes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term avg. (1950-2013) | 10.8 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| 2014 season | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Colorado State (issued Apr. 9th) | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| TropicalStormRisk.com (issued Apr. 9th) | 11 | 5 | 2 |

| NC State (issued Apr. 16th) | 4 to 6 | 1 to 3 | 1 |

| UK Met Office (issued May 21st) | 8 | 5 | (no prediction) |

| NOAA (issued May 27th) | 6 to 11 | 3 to 6 | 0 to 2 |

As always, it’s worth noting that even inactive seasons can still have strong, damaging storms, as we saw last year when Hurricane Arthur made landfall in North Carolina. This is Hurricane Preparedness Week, so it’s a good time to review NOAA’s preparedness guide to make sure you’re ready in the event of tropical storm.