This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

One of North Carolina’s most widespread — and most recent — severe weather outbreaks came on April 16, 2011, when a line of storms encountered ideal environmental conditions to strengthen and spawn a record number of tornadoes across the state.

A Severe Weather Setup

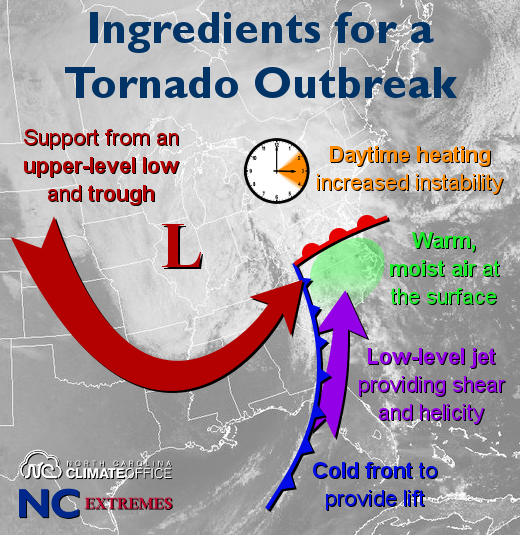

Like many of our extreme weather events, this record-setting tornado outbreak resulted from a combination of favorable ingredients:

- Leading up to the event, a warm front moved north across the state, bringing in a feed of warm, particularly moist air from the Gulf of Mexico. Dew points climbed into the 60s, providing fuel for strong thunderstorms.

- A surface cold front moved across the Appalachians on the morning of Saturday the 16th. The rising air along the frontal boundary, along with upper-level support from a trough in the jet stream, provided the lift needed to initiate thunderstorm development.

- The front crossed central North Carolina in the mid to late afternoon hours during the hottest part of the day as temperatures climbed into the mid 70s. Combined with the moisture present near the surface, that extra warmth meant maximum instability. One measure of that instability, called Convective Available Potential Energy or CAPE, was highest across the eastern Piedmont, which gave support for strong updrafts and severe thunderstorm growth across that region.

- A low-level jet coming from the south meant strong winds just a few thousand feet off the ground. That resulted in wind shear of more than 50 mph across the state and high storm-relative helicity: a potent cocktail that meant spiralling air near the ground could be tilted vertically by thunderstorm updrafts, becoming the foundation for tornadoes. Helicity values across central North Carolina exceeded 600 meters² per second², which the National Weather Service classifies as “Extreme” levels.

With these ingredients set to converge over North Carolina and this system having a history of producing dangerous, long-lived tornadoes, the Storm Prediction Center’s Friday afternoon outlook included the eastern half of the state in a Moderate Risk of severe weather. On Saturday, that was upgraded to a High Risk with a 30% probability of a tornado within 25 miles of a given point across that region.

Around noon on Saturday, the SPC issued a tornado watch for much of the state, noting it as a “particularly dangerous situation” — wording used most commonly across the midwest, and for only the most violent tornado outbreaks.

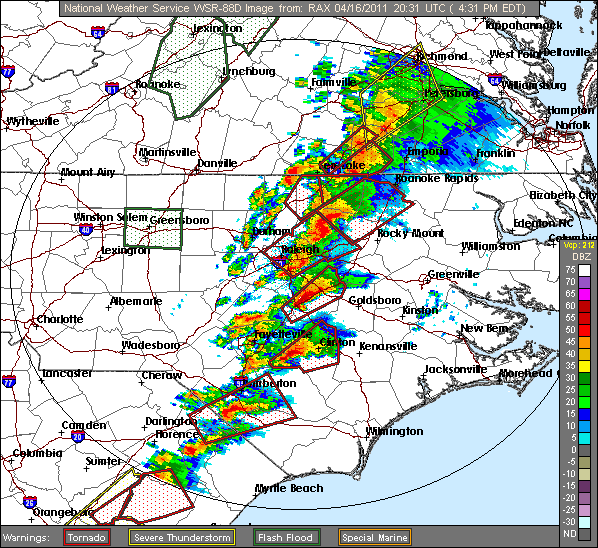

Storms Cross the State

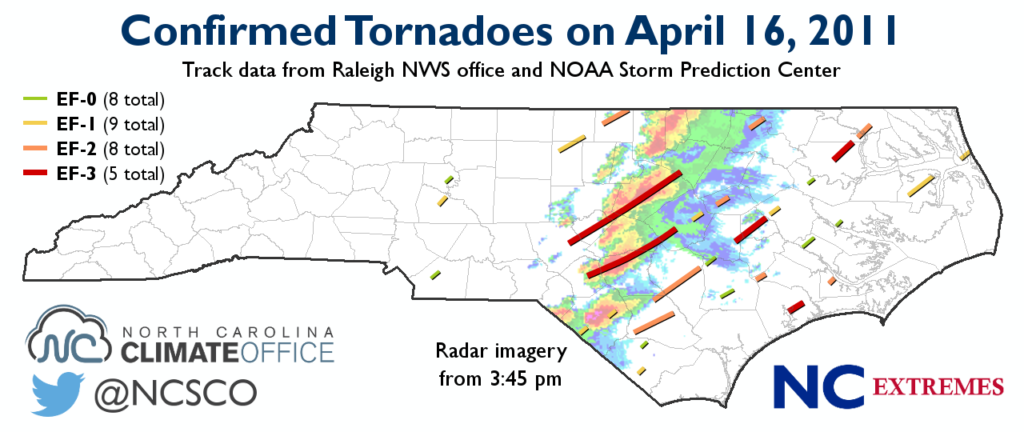

A continuous line of showers and storms along the cold front moved across western North Carolina on the morning of Saturday, April 16. The first tornado warning was issued at 12:40 pm for a storm that spawned an EF-1 tornado just north of Salisbury. As the line continued moving east, it also produced EF-0 tornadoes in Davie and Union Counties.

Over the next few hours, something unusual happened. As the Raleigh National Weather Service office notes in their thorough case study of this event, supercells often form ahead of a squall line. But in this case, the high-shear environment prevented supercells forming ahead of the line, so the squall line itself — supported by the strong lift along the frontal boundary that could overcome the shear — evolved into a series of strong supercell thunderstorms, with small gaps between them.

The northernmost tornadic supercell developed around 2 pm over Alamance County as an EF-1 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, eventually crossing the Virginia border north of Roxboro as an EF-2. These two tornadoes destroyed several homes, tore roofs off of others, and ripped trees out of the ground.

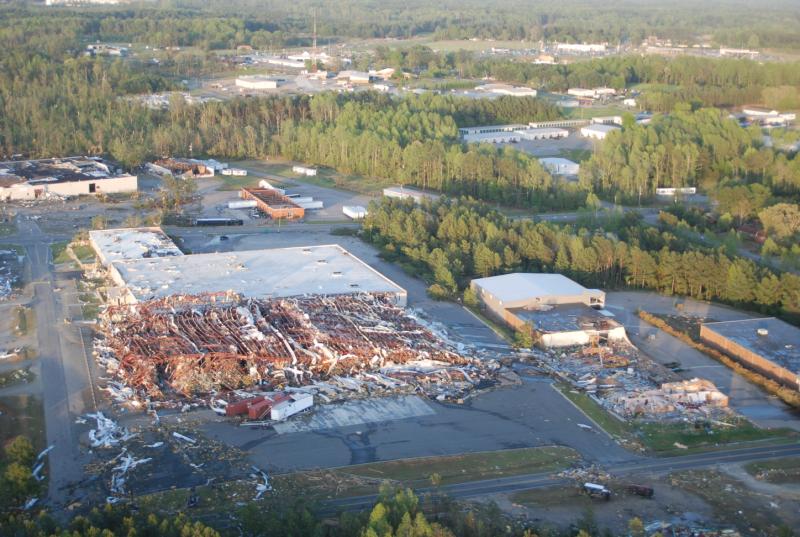

Around 2:45 pm, a supercell developed over Moore County, spawning a tornado that reached EF-3 strength — the first of five that day across the state — with wind speeds estimated at 160 mph as it moved through Sanford, destroying several businesses. That supercell continued moving northeast into Wake County at EF-1 strength, crossing downtown Raleigh and causing widespread tree and building damage. It finally weakened over southern Franklin County, but that supercell produced another short-lived EF-2 tornado near Roanoke Rapids.

Just to the south of that cell, another tornadic supercell emerged over Hoke County. It tracked across Fayetteville at a maximum EF-3 strength and caused more than $5 million in damage to Ben J. Martin Elementary School. That tornado weakened slightly as it moved into Johnston County, but it remained a destructive tornado as it passed through Dunn and Smithfield. That supercell produced two other brief tornadoes: an EF-1 near Micro in Johnston County, and an EF-2 near Wilson.

The next most southerly supercell had been tornado warned over South Carolina, and it spawned two brief EF-1 tornadoes over Robeson County. It then produced an EF-2 tornado that crossed Sampson County, an EF-3 just west of Goldsboro over Greene County, and another EF-3 over Bertie County.

By Saturday evening, the Piedmont was in the clear behind the front, but parts of the coast remained in their path. One supercell spawned tornadoes on and off between Bladen County and Kitty Hawk, and another produced an EF-3 tornado that touched down near Jacksonville, with that cell also briefly spawning an EF-2 south of New Bern.

The Damage Done

All told, 32 tornadoes were confirmed across the state that day, breaking the old record of 20 tornadoes from May 7, 1998. These tornadoes weren’t the strongest on record — there were four F-4 tornadoes across the coast on March 28, 1984, when 14 tornadoes responsible for 41 fatalities occurred — but the April 16, 2011, event was the most numerous and possibly most widespread tornado outbreak for the state.

Note: The original version of this post cited the tornado count on this date as 30 based on the data available at the time. The updated analysis from the Storm Prediction Center increased that count to 32 tornadoes, adding two more along the coastline in Pamlico and Dare counties, seemingly where tornadoes lifted over water and touched down again on the other side.

The total property damage was estimated at just over $328 million, about 88% of that coming from the the Sanford-Raleigh and Fayetteville-Smithfield tornadoes. In total, 304 injuries and 24 deaths were reported.

Although damage from these strong tornadoes was inescapable, it was clear in the days and hours before the event that there was a strong potential for this sort of severe weather — a testament to the improvements in our forecasting and monitoring abilities.

The Raleigh National Weather Service office reports that the average lead time for tornado warnings in their forecast area was 26 minutes, and the average lead time for warnings where fatalities occurred was 28 minutes. Both are above the national average lead time of about 13 minutes, and that’s still an improvement since the 1980s, when lead times for tornadoes were generally five minutes or less.

While the April 16, 2011, tornado outbreak was the most numerous for North Carolina, those advancements certainly prevented it from collecting any records for more grim statistics.