It is National Hurricane Preparedness Week, so we begin our 2014 summer outlook series with a primer on seasonal hurricane outlooks.

As the beginning of hurricane season approaches each June, research teams around the world release their predictions for the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic over the coming summer and fall. Making predictions so far in advance about such fleeting phenomena may seem like nothing but guesswork, but there is science behind their forecasts, as explained in these frequently asked questions about the pre-season outlooks.

Who makes these forecasts?

Ten years ago, only a handful of researchers were issuing pre-season hurricane outlooks. Today, at least a dozen organizations on both sides of the Atlantic are producing their own forecasts. This includes university-based research groups such as the Tropical Meteorology Project at Colorado State University, which is led by Drs. Philip Klotzbach and William Gray. NC State University also has a group of hurricane researchers led by Dr. Lian Xie in the Coastal Fluid Dynamics Lab. National forecast offices such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the U.S. and the U.K. Met Office also produce pre-season forecasts, as do several private forecasting companies.

If computer models can’t predict the weather more than a week ahead of time, how can seasonal hurricane models predict conditions several months away?

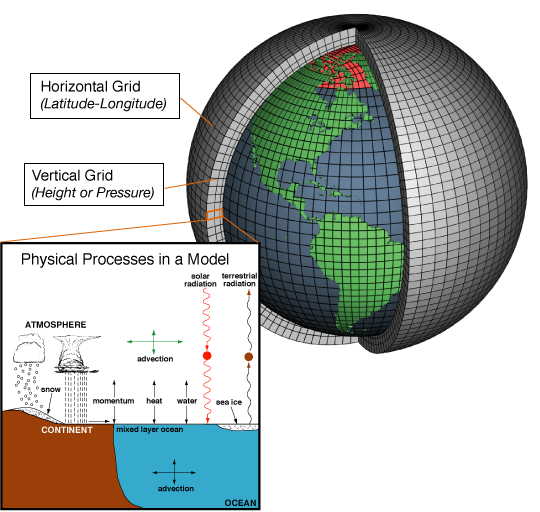

While both models attempt to predict some aspect of the weather, they do it in very different ways. The short-term computer models that run several times each day are dynamical models. They start with the latest observations, then step slowly through time and use equations of atmospheric and oceanic dynamics, or physical processes, to predict how conditions will change at many different points spaced several miles apart. These models can be run across the globe, but are often run over North America or even smaller regions like North Carolina.

Models tend to be unreliable beyond five to seven days because our knowledge of the atmosphere isn’t perfect, because we can’t predict conditions at every point on earth so that model runs are completed within a few hours, and because of the inherent chaos in nature.

For the most part*, seasonal hurricane models are statistical — not dynamical — which means their forecasts are not explicitly based on physical processes. Instead, these models use statistical relationships based on environmental conditions known to impact the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic. Essentially, by knowing what the tropical activity was like with various oceanic and atmospheric conditions in previous years, these models can attempt to predict what conditions might be like in the current year, given those statistical relationships and the current conditions.

* Research teams at Florida State University and the UK Met Office have recently been using dynamical seasonal hurricane forecast models. Like short term models, they include equations for oceanic and atmospheric processes, but they run at a much coarser resolution. Instead of actual hurricanes showing up the models, features like low pressure and high vorticity, or spin, are used to identify storms. An ensemble, or large set of models with slightly different initial conditions, is run to show the uncertainty in the possible outcomes, which helps them make their seasonal predictions.

What conditions do seasonal hurricane models use as predictors?

Each model uses slightly different predictors based on the research and inputs from the developers, but for the most part, they all look at a few main environmental factors that are known to affect tropical activity.

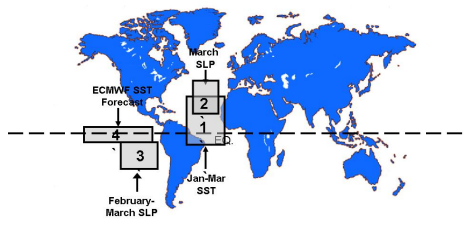

One of the more helpful predictors is often the phase of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is based on the sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures — El Niño conditions — are often associated with a strengthening of the trade winds across the Atlantic basin, which causes more vertical wind shear and makes it tougher for tropical storms to form. Similarly, some models look at sea level pressure over the equatorial Pacific since it can be linked with the development of El Niño or La Niña conditions.

Pre-season conditions in or over the Atlantic Ocean are also important. When sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic are lower than normal, it can be more difficult for storms to develop since they extract heat energy from the ocean surface through condensation. Cooler-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic are also associated with a strengthening of the Bermuda high pressure system, which can cause stronger trade winds and increased wind shear, both of which directly affect tropical storm development.

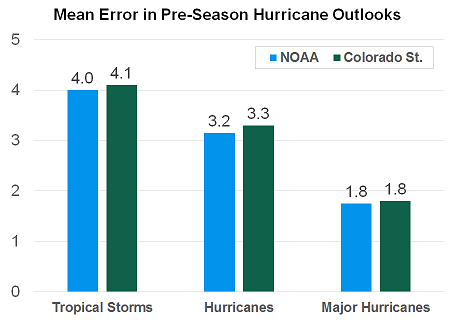

How accurate are seasonal hurricane outlooks?

Between 2004 and 2013, the pre-season forecasts from two of the longest-tenured research teams at NOAA and Colorado State University have been off by about 4 for tropical storm counts, about 3 for hurricane counts, and almost 2 for major hurricane (category 3 and above) counts. Some groups such as the team at Colorado State release multiple outlooks in the months preceding the start of hurricane season. As you might expect, models run closer to the start of the season tend to perform better because they include the most up-to-date information about the state of the environment.

Almost all seasonal hurricane models struggled to predict the relatively inactive 2013 season, which had 13 tropical storms, two hurricanes, and no major hurricanes. Most forecasts predicted 15 or more tropical storms and at least five hurricanes, a few of which would be major storms. So why did almost every forecast miss so badly that year?

There are several possible reasons. Research at Colorado State identified a late-spring weakening of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, which is a cyclical warming and cooling of the ocean surface. Another potential culprit is wind-blown dust from the Saharan Air Layer, which inhibits storm development by increasing vertical wind shear, increasing downdrafts within the environment, and blocking solar radiation from reaching and warming the sea surface. The neutral ENSO phase during the summer of 2013 also gave few climatological clues about whether the number of storms would be above or below normal.

Can seasonal hurricane models predict landfalling storms?

Although there may be some statistical relationships between pre-season environmental conditions and the number and locations of landfalling storms, most groups have moved away from including such predictions with their outlooks for two main reasons. First, as NOAA states, “[h]urricane landfalls are largely determined by the weather patterns in place as the hurricane approaches, which are only predictable when the storm is within several days of making landfall.”

Also, suggesting that landfalls are unlikely in a particular location may discourage preparedness by residents, and, again quoting NOAA, “[i]t only takes one storm hitting an area to cause a disaster, regardless of the overall activity predicted in the seasonal outlook.”