It was an environmental domino effect that was hard to fathom considering huge swaths of western North Carolina had been under water just two months earlier following Hurricane Helene.

On December 6 of last year, a wind gust toppled power lines in rural McDowell County. A spark of electricity then carried from the lines onto the landscape – the hills just east of state Highway 80 near Lake Tahoma.

This region is crisscrossed by streams such as Buck Creek, which overflowed as a wave of mud and water into the nearby community during Helene in late September. Now the same area was on fire, illuminating another of the storm’s impacts that has become increasingly apparent since the floods receded.

The main driver of that impact was not water, but wind. Just 12 hours after its landfall at Category-4 intensity, Helene’s remnant eyewall crossed western North Carolina. With observed wind gusts of up to 106 miles per hour on Mount Mitchell, the storm snapped and tossed trees like toothpicks, leaving them littered across the land.

A bullseye of severe tree damage occurred in western McDowell County, including where December’s 520-acre Buck Creek fire – along with the 644-acre North Fork fire and the 220-acre Crooked Creek fire in January, and April’s 2,085-acre Bee Rock Creek fire – ignited in recent months.

In storm-damaged areas, these fires are only the beginning of Helene’s long-term impacts. Following the hard hit last fall, the fire regime will continue to evolve, so sound management as well as established partnerships and monitoring efforts will help our state weather this storm’s fiery aftereffects for years to come.

Assessing the Impact

While Helene’s record rainfall totals and river crests captured plenty of headlines in the days following the storm, photos from the hillsides across western North Carolina soon revealed a devastating blow – literally – from the winds that lashed the region.

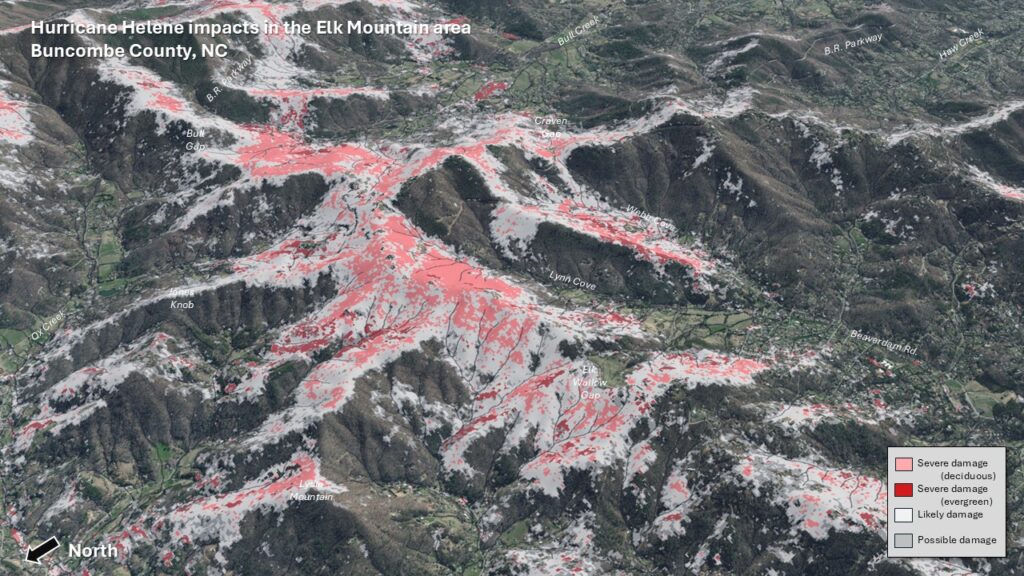

Aerial imagery captured entire mountainsides where the once-lush green vegetation had been stripped of its leaves and violently felled by the storm. A damage appraisal by NC Forest Service estimated that 822,000 acres of timberlands in the state were damaged, including more than 130,000 acres in McDowell County alone, with a total economic loss of almost $214 million.

While impacted areas were initially difficult to reach over the ground, remote sensing technology such as high-resolution satellite imagery has offered a clear view of Helene’s tree damage and its significant variations across the region.

Dr. Steve Norman, a research ecologist at the US Forest Service’s Southern Research Station in Asheville, has been at the forefront of this data, and his HiForm team’s outputs include local views of the damage quantified by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, or NDVI.

Comparing the infrared light reflected by vegetation between the fall of 2023 and 2024, these products highlight areas of heavy damage just around the corner from almost untouched trees – a very different result than what we might see when a hurricane moves over the flatter eastern part of our state.

“The most important insight we’ve gained from mapping Helene’s wind impacts across western North Carolina’s rugged terrain is how erratic and patchy blowdown was compared to the typical impacts we see on the Coastal Plain,” said Norman. “In the Mountains, blowdown was not simply related to wind exposure.”

Instead, he noted a number of factors that seemed to affect the degree of damage. Among them were that trees above 4,800 feet had already started their seasonal color change, so their leaves were blown off more easily. Meanwhile, lower-elevation trees, especially oaks, were weighed down by their leaves and more easily uprooted.

“In other words, had Helene happened a few weeks later, we might not have seen so much tree damage,” he said. “When a hurricane comes, resistant leaves are a liability.”

Heavy rainfall from the pre-storm frontal event also contributed to the damage, weakening the soil around tree roots before the gusty winds moved in.

“Predecessor rain in the two days prior to Helene’s arrival was usually more than what fell during the day of the storm, and this excess rain made trees with shallow roots particularly unstable,” said Norman.

South-facing slopes perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction saw greater damage, along with areas in the path of the storm’s locally intense downbursts.

“It was a tropical storm, with hurricane-force gusts, with terrain enhancement. These trees with a summer or early fall canopy simply couldn’t handle this with the wind and the rain,” said Trisha Palmer, the Warning Coordination Meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Greenville-Spartanburg, SC.

Her office produced a wind gust analysis in the wake of the storm showing a corridor of the highest winds northeast of Asheville. Some likened the treefall in these areas to tornado damage, but on a much larger scale.

“This is like nothing any living person has ever seen in this part of the country,” added Palmer.

Fire Danger, Now and Later

Immediately after Helene and our storm-soaked September, the state entered a drier weather pattern, beginning with our 3rd-driest October on record. As drought developed, including in the Mountains by December, it didn’t take long for the impacts of that storm damage to come to light.

This winter and spring, it wasn’t the huge fallen trees catching and carrying fire; “it’s still too early for that,” noted Norman. Instead, smaller debris such as leaves, pine needles, and fallen branches fueled many of the wildfires across the region. And just as you might notice when adding this kind of kindling to a backyard burn, that made these fires burn much hotter.

“In many cases, the intensity coming off the flames, even backing fire, was two to three times more intense heat than you would normally expect,” noted NC Forest Service’s regional foresters in comments shared with the State Climate Office.

Once these fires had ignited from sources ranging from downed power lines to unextinguished cigarettes to lightning strikes, that dead fuel burned easily due to the ongoing drought, and the fires were difficult to access and contain amid the rugged terrain strewn with larger debris.

“Crews often needed two sawyers in front of a dozer just to clear trees and debris so the dozer could push a fire line in areas where storm damage was significant,” reported the NC Forest Service staff.

It’s natural to wonder what the future of our fire seasons will look like in these damaged areas, and we already have a good idea of how that danger will evolve – and increase – in years to come.

Part of that is how the fuel loading will be enhanced once those larger downed trees dry out and decompose.

“In the future, as the large wood starts to decay and the bark is lost, it will become a major smoldering and smoke problem for the greater region that will persist for decades,” said Norman.

In addition, new trees and brush growing back as part of the next generation of forest succession will enhance the fire danger, particularly before a new canopy has developed that can shade that new growth from sunlight and shield it from the wind.

Managing the Risk

Fighting these fires of the future will require learning lessons from the past and implementing the best practices of the present.

Among those practices is prescribed burning: using smaller and lower intensity burns at regular intervals to help manage fuel loads and reduce the risk of wildfires that are much larger and more difficult to control.

We’ve seen the impact that regular prescribed burns — or the lack thereof — can have in our own backyard. When Hurricane Hugo ripped through the Carolinas in 1989, it destroyed four years’ worth of harvestable timber in a day. One study of plots in coastal South Carolina found that even 24 years later, fuel loads remained higher than pre-storm levels in damaged stands that weren’t treated with prescribed burning.

Across Louisiana and southern Mississippi, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 destroyed 320 million trees, resulting in 20 to 30 times the normal fuel loading from tree debris. In the aftermath, Mississippi’s National Forest staff created fire breaks to limit the spread of developing fires, and those had immediate benefits. In 2006, the Burnt Dog fire was contained after burning just 35 acres, and the fire breaks were credited with protecting multiple homes.

That’s especially relevant in North Carolina, which has more acres in the Wildland-Urban Interface than any other state. To that end, NC Forest Service staff said they’re bolstering public outreach efforts, including encouraging firewise landscaping to protect homes, in response to hazards they’ve already seen this spring.

“Debris piled around houses has caused significant issues with structure protection, especially if this debris had been cut and stacked near a home or a structure. These cut piles dried more readily and were available to burn and contribute to fire intensity,” they noted.

Of course, folks in western North Carolina are no strangers to wildfires. The fall of 2016 was a notable fire season across the southern Appalachians, including the Chimney Tops 2 fire that reached Gatlinburg, TN, and the Party Rock fire that prompted evacuations in Chimney Rock.

Since 2016, one of the biggest changes at NC Forest Service has been the ongoing departure of many staff who worked those events, and they still have a number of vacancies statewide that can stretch their resources thin during active fire seasons like this year’s.

“Staffing levels and the experience of staff were huge, challenging factors for us statewide this spring. For example, 50% of employees in NCFS Region 2, which is comprised of counties in the Piedmont and Sandhills, have less than five years of experience,” they noted.

That staffing includes both new employees and more experienced staff who can train and mentor them for jobs such as forest fire equipment operators and fire line supervisors. It’s a reminder that management starts with man (and woman) power to tackle these sorts of events.

A Coordinated Response

No agency is alone in confronting the forestry and fire impacts from Helene. For NC Forest Service, partnerships with other state, regional, and federal agencies are critical, both for handling fires as they arise and for preparing on a daily, monthly, and seasonal basis.

North Carolina’s Fire Environment Committee – composed of NC Forest Service regional staff and partner agencies and organizations, including the State Climate Office – meets twice per year to discuss management and monitoring challenges and needs.

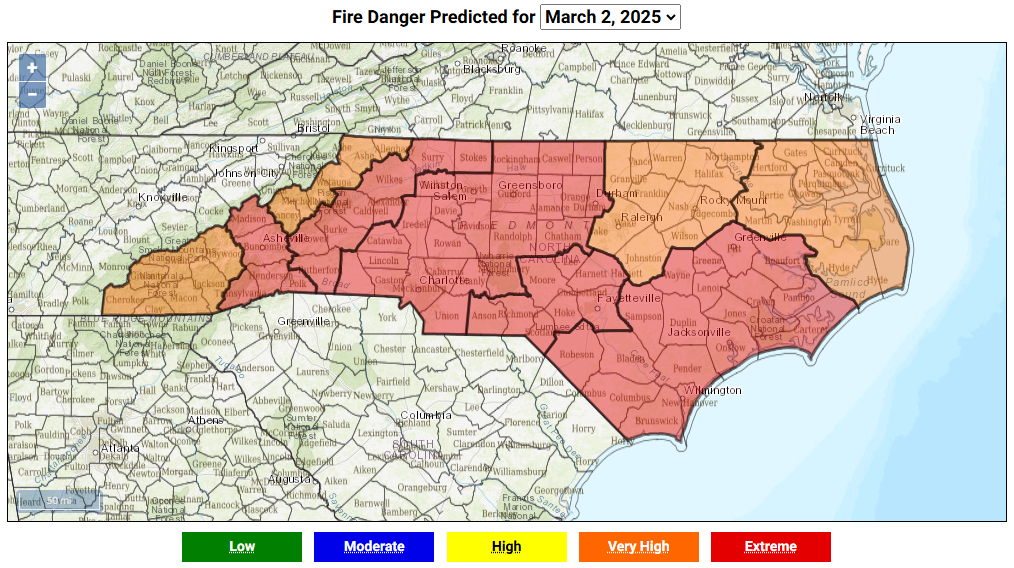

This committee has opened the door to new collaborations, such as holding joint training sessions for new staff among those agencies and conducting prescribed burns with groups such as NC State Parks, along with advancing how we communicate fire danger, which led to resources such as our public-facing state fire danger forecast map.

“This year-round coordination, preparation, and relationship-building for fire environment-related topics is crucial to help better sustain operations when emergencies occur,” noted the NCFS staff.

One key resource for fire weather monitoring over the past 12 years has been the Fire Weather Intelligence Portal, which combines weather observations and fire danger estimates and forecasts in an interface that land and fire managers can easily use, even on their phones at a burn site. That’s especially helpful for new staff as they get up to speed.

“It takes minimal effort to learn the functionality of the Portal,” said Jamie Dunbar, the Fire Environment Staff Forester at NC Forest Service. “It is organized in an easy-to-navigate way related to past, current and forecast conditions, and we can extract tables and graphics very easily to use for informing others.”

The Portal has been developed and maintained by the State Climate Office with funding from NC Forest Service, and it’s available region-wide thanks to support from the USDA Southeast Regional Climate Hub, which works with natural resource managers on risk assessment such as with wildfire danger.

Other partners also help with fire planning and preparedness. Among them, the National Interagency Coordination Center provides weekly and seasonal fire danger outlooks, and regional guidance via eleven geographic coordinating groups, including the Southern Area Coordination Center serving North Carolina.

In addition, the National Weather Service and its local offices produce seven-day fire danger forecasts for monitoring stations including our ECONet and on-demand spot forecasts for prescribed burn and wildfire events. This information helps fire managers make decisions about when and where to burn, or how to mobilize resources in anticipation of potential wildfire outbreaks, as we had on several days this March.

An old adage says that it takes a village to raise a child. In a similar vein, handling the hazards ahead related to Helene’s lasting damage, along with our day-to-day fire episodes, will take multiple organizations and the collective expertise of their staff. That includes researchers such as Dr. Steve Norman at US Forest Service, meteorologists like Trisha Palmer at the National Weather Service, and the foresters including Jamie Dunbar at NC Forest Service.

“When faced with the current challenges we have before us in North Carolina – including the heavy fuel loading and access limitations post-Helene, our vacancy rate and staffing levels, an imbalance of experienced to inexperienced personnel, and future extreme weather events and natural disasters – a unified approach across multiple agencies, jurisdictions, and levels becomes much more important and valuable,” concluded the NC Forest Service staff.

“It’s essential to providing the needed response to protect the lives, property and natural resources at risk.”