Hurricane Matthew won’t go down in the record books as a landfalling storm in North Carolina. At Category-1 strength as it grazed the coastline, it also won’t rank highly among the strongest storms to affect our state. However, its widespread impacts packed a punch that few other storms in our state’s history can match.

North Carolina was the final leg of Matthew’s journey that began two full weeks earlier, when the National Hurricane Center first identified an area of interest off the African coast. Matthew was first classified as a tropical storm on September 28, and just two days later, it underwent rapid intensification from a Category 1 to a Category 5 hurricane.

With maximum sustained winds of 161 mph at its peak intensity on October 1, Matthew became the strongest Atlantic hurricane since Felix in 2007. Warm water in the Caribbean Sea helped Matthew rapidly gain steam, but it also intensified in spite of moderate vertical wind shear, which typically hinders storm development.

Unlike Felix and many other storms that have taken a southerly track across the Caribbean, Matthew made a turn to the north under the steering influence of ridge near Bermuda. That put it on a similar track as Hazel — North Carolina’s only landfalling Category-4 hurricane on record — with plenty more warm water awaiting over the Gulf Stream that could help Matthew re-intensify after a trip across Jamaica and Cuba.

Matthew’s slow movement and its impending interaction with a stationary front off the east coast made forecasting its track particularly difficult. Initially, it appeared on a direct collision course with the southern coast, à la Bertha in 1996. Later, forecasts showed Matthew curving away from the coast in a loop with an impending second encounter with the Bahamas.

Ultimately, the front retreated inland, which allowed Matthew to track farther north and closer to the North Carolina coast. The storm’s only US landfall came on Saturday morning just north of Charleston, and afterwards, it hugged the coastline as a Category-1 storm. However, that diminished strength didn’t lessen the storm’s impacts.

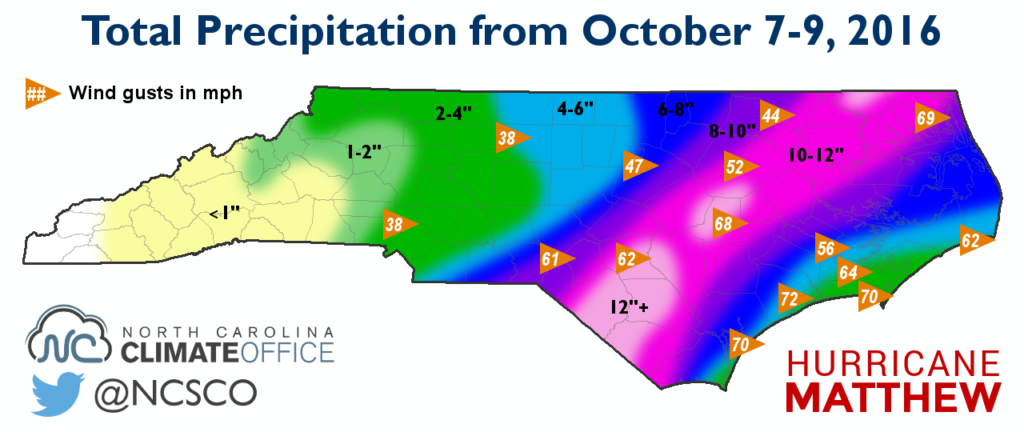

Rain from Matthew moved over North Carolina beginning early on Saturday, and for the next 24 hours, there were few breaks in the rain across the eastern half of the state. Totals amounted to 2 to 4 inches in the Triad and Charlotte, 6 to 8 inches in the Triangle, and more than 10 inches across much of the interior Coastal Plain.

The highest totals came in Wayne County, including 15.24 inches at the Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, and Cumberland County, with CoCoRaHS reports of 14.32 inches near Godwin and 14.71 inches near Hope Mills.

Tropical storm-force wind gusts were reported across the Coastal Plain and eastern Piedmont. Along the immediate coastline, gusts as high as 70 mph in Wilmington and Beaufort and 72 mph in Jacksonville were observed.

As we have seen in Hurricane Fran and other storms, that combination of ground-soaking rains and high winds is always a dangerous one. Matthew brought a bit more rain and slightly weaker winds than Fran, but the outcome was similar: widespread downed trees and more than 814,000 power outages — about half as many as at the peak during Fran — at one point on Sunday morning.

As the damage assessment started and electricity began to be restored, the storm’s greatest threat emerged. The heavy rain falling on already saturated ground meant water spilling onto roads, out of rivers and tributaries, and breaching dams, especially near Fayetteville, which received up to 10 inches of rain just one week before Matthew.

Similar back-to-back heavy rain events resulted in catastrophic flooding during Hurricane Floyd in 1999, and several gauges along the Neuse, Cape Fear, and Lumber rivers have already exceeded their record levels from Floyd — high-water marks that at times seemed unbreakable.

That water is working its way down the river basins to the coast, which means that despite the clear, fall-like weather this week, the flooding threat isn’t over yet. Because of that, we also don’t yet have a full picture of Matthew’s damage across the state, particularly to flooded homes, business, and farm fields.

At the time of publication, 10 deaths in North Carolina have been attributed to the storm, mostly due to flooding. That already puts this storm just outside the top 10 of North Carolina’s deadliest hurricanes, and the eventual cost is likely to place Matthew well within our top 10 costliest storms as well.