Ascending temperatures arrived in April, while the rain that moistened our March was mostly absent. However, our few thunderstorms did bring an icy, potentially record-matching surprise.

Heating Up in April

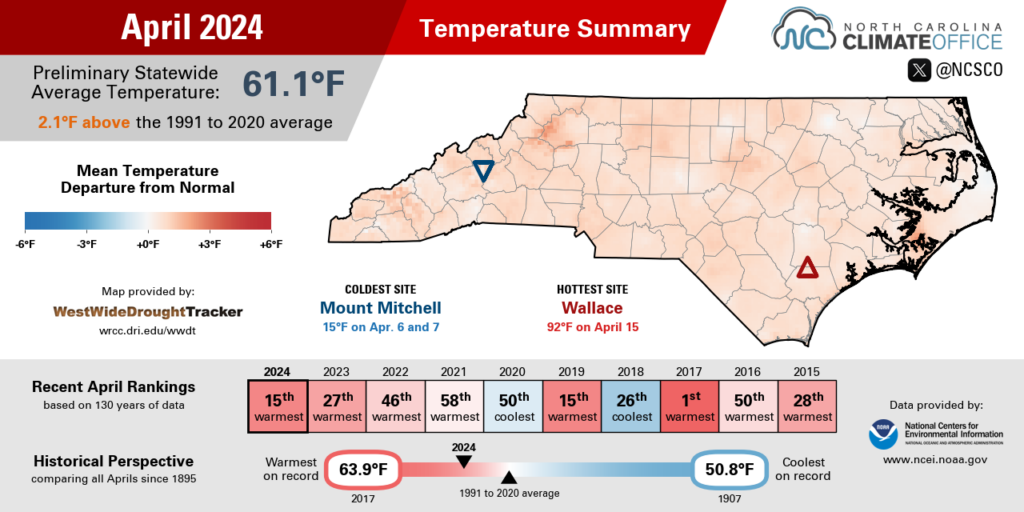

Springlike warmth, and at times even summerlike heat, emerged in April, lifting our overall temperatures above normal for the month. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a statewide average temperature of 61.1°F and our 15th-warmest April since 1895.

Locally, it was the 2nd-warmest April on record in Raleigh, the 5th-warmest in Charlotte, and the 8th-warmest in Hickory. At all three sites, it was the warmest April since 2017.

The heat hit early last month, with temperatures on April 2 climbing into the 80s from the mountains to the coast. The mercury climbed as high as 88°F in Goldsboro, which set a new daily record high dating back to 2000. Also on that afternoon, New Bern and Raleigh reached 86°F while Asheville topped out at 84°F in its first 80-degree day of the year so far.

Perhaps even more impressive were the morning temperatures that day. Fayetteville and Raleigh dropped to just 66°F – more than 20 degrees warmer than normal – which was a daily record warm low temperature at both sites.

The hottest weather arrived by mid-month as high pressure set up to our south. On April 15, temperatures hit the 90-degree mark for the first time this year in North Carolina, including highs of 91°F in Smithfield and Clayton in Johnston County. For our ECONet station at the DAQ Air Profiler, that was its earliest 90-degree day since hitting that mark on March 28 in 2020.

Any wintry chill was largely confined to just one weekend last month. Morning low temperatures on April 7 dropped below freezing in parts of the Mountains and northwestern Piedmont, including chilly 29°F readings in Mocksville and Yadkinville. In those areas, that cooler weather occurred near or a bit before the average last spring freeze dates, so while it wasn’t untimely, it may have felt out of place given the warm spring until then.

The next day brought another cooldown, but for an out-of-this-world reason. A partial solar eclipse was visible across North Carolina on the afternoon of Monday, April 8, and we measured its impact down to the minute with our ECONet.

All of our stations saw at least a 75% decrease in solar radiation values, but the greatest change occurred farther west. On Mount Jefferson, where 88% of the sun was blocked by the moon and scattered clouds were moving over, we recorded an impressive 98% decrease in solar radiation.

As the incoming sunlight decreased during the eclipse, so did our air temperatures. On average across the network, we saw a 4.4°F drop, with the biggest changes coming at two of our high-elevation sites in the southern Mountains. Wayah Bald Mountain recorded a 10.3°F decrease, and Frying Pan Mountain dropped by 11.7°F, from 64.4°F to 52.7°F, that afternoon.

April Showers Come Up Short

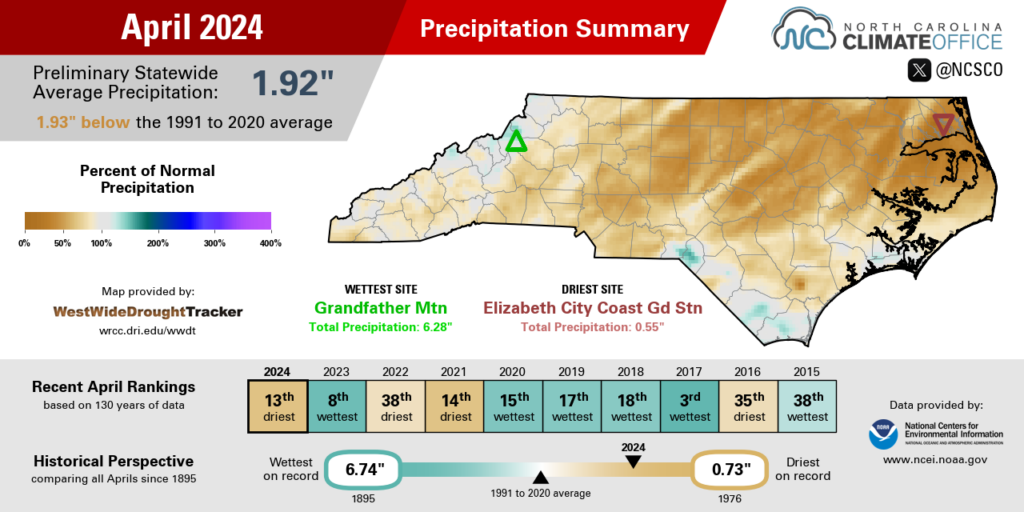

After a muddy March, April brought more sun than rain, which left us drier than normal across the state. NCEI notes a statewide average precipitation of 1.92 inches, which ranks as our 13th-driest April out of the past 130 years.

With only 0.55 inches of rain all month in Elizabeth City, it was the 3rd-driest April on record there, and the driest since 1967. Plymouth had just 0.84 inches, which also made for the 3rd-driest April in the past 76 years.

Greensboro’s 1.23 inches of rain made for its 10th-driest April, while the 1.16 inches in Greenville and 1.02 inches in Raleigh ranked as the 8th-driest April for both sites.

Parts of far western North Carolina fared a bit better thanks to heavier rain during a frontal passage on April 12. Lake Toxaway had up to 2.50 inches that day, with 2.35 inches on Mount Mitchell and 1.98 inches in Boone.

That boosted their monthly totals a bit closer to normal, although most western locales were still a bit on the dry side for April. Boone was 0.76 inches below average for the month, Morganton was 1.02 inches below average, and Hendersonville was 2.01 inches below average in its 21st-driest April since 1899.

Despite the dry April, most of the state is still holding near its normal precipitation so far this spring. Asheville is slightly above its seasonal average with 8.78 inches up to this point, and deficits in the western Piedmont are around an inch, with Charlotte 1.02 inches below normal and Hickory 0.99 inches below normal for the season to date.

Areas along the coastline continue to carry a surplus through the spring thanks to their wet March. Elizabeth City, for instance, remains more than 3 inches above normal for March and April, and is on pace for its 11th-wettest spring on record.

The driest areas at this point in the season are in the eastern Piedmont and western Coastal Plain. Greenville and Raleigh are 2.25 and 2.26 inches below normal, respectively, through March and April, while Smithfield is 2.51 inches below average.

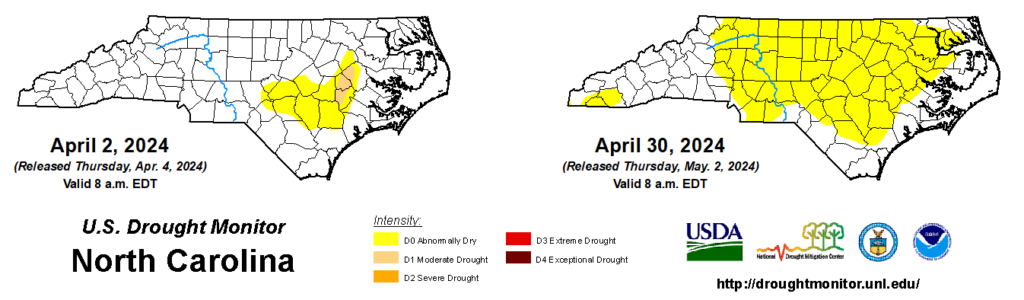

That seasonal-scale dryness is evident with Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions now covering more than half of the state on the latest US Drought Monitor map. While deeper soil moisture remains near normal for most areas thanks to our wet March, the upper layers of soil have been drying out, aided by the warmer weather and several windy days last month.

While dry days were initially helpful for farmers to get into the fields and begin their springtime planting, the continuing dryness has slowed that progress in some areas. Streamflow levels have also been steadily declining, and as we enter May, it’s safe to say that a bit of rain would be a welcome sight for crops and creeks alike.

Hefty Hail from Severe Storms

Much of eastern North Carolina may have missed out on the heaviest rainfall last month, but they had a heaping helping of hailstones on Saturday, April 20, some of which may have rivaled the largest we’ve ever seen in the state.

Thunderstorms that afternoon along the South Carolina border yielded dozens of large hail reports, including golfball-sized hail in Pembroke and softball-sized hail in downtown Lumberton, as reported to the National Weather Service office in Wilmington.

If verified, those largest hailstones estimated at 4.5 inches in diameter would tie the state record, based on data from the Storm Prediction Center. Since 1955, there have been seven other reports of 4.5-inch hail in North Carolina, with the most recent occurring on May 24, 2000, in Burke County.

While it’s not too surprising to see hail at this time of year – climatologically, April through June are our most common months for hail – it takes some special atmospheric ingredients to produce hail as large as we saw last month.

On the Climate Blog, we have previously covered ingredients for hail formation, including a low freezing level to give more vertical space for ice accrual, strong updrafts to keep growing hailstones suspended in clouds, and upper-level wind shear so that updrafts are offset from the downdrafts that would otherwise push hailstones back toward the ground.

The environment on April 20 featured each of those ingredients, including steep low-level lapse rates that indicated rapid cooling above the ground, and 40 to 50 knots of wind shear over the lowest 6 kilometers, or 3.7 miles, of the atmosphere.

But other factors were at play on that day as well, each of which helped the hail grow even larger. For one, the overall instability in the atmosphere was high that day. The Convective Available Potential Energy, or CAPE, was more than 2,000 Joules per kilogram, not too far from the extreme levels seen in major tornado outbreaks such as the one on March 28, 1984.

And precipitable water – a measure of the depth of liquid if all of the water vapor in the atmosphere above a point were to fall as precipitation – sharply declined to the west of the peak values right along the coastline, giving a drier mid-level environment in which the thunderstorms developed.

While it may seem counterintuitive since hail is a form of precipitation, excess moisture in the clouds can easily weigh down hailstones and cause them to fall early as gravity pulls them downward.

With those factors lined up over southeastern North Carolina, the end result was a different sort of ice storm than we’re used to seeing around these parts, but a springtime variety that may have been just as hazardous – and certainly as memorable – as any during our winter months.