Things that take a lifetime to build can be destroyed in mere moments.

Case in point: March 28, 1984, when a line of tornadoes carved a path like a buzzsaw across eastern North Carolina.

Faye Watson, a resident of Red Springs – a Robeson County town in the crosshairs of one of the four F-4 tornadoes that tracked through the state that afternoon – recalled to The Robesonian just how quickly it all unfolded.

“All of a sudden we heard a whistling noise. It sounded like a train, and we realized it was a tornado,” said Watson. “We told the children to get down to the basement immediately. As we ran we grabbed some pillows, but by the time we got down there, everything was pretty much over.”

Watson’s family escaped unscathed, but many others did not during the deadliest tornado outbreak of the 20th century in our state.

On the 40-year anniversary of the Carolinas outbreak, we look back at what made March 28, 1984, such a destructive day, how the events unfolded, and its rightful place among our most impactful weather events.

A Potent Pattern

Severe weather in the springtime is hardly uncommon, but it still took a unique set of ingredients to support such strong and long-lived tornadoes on this date.

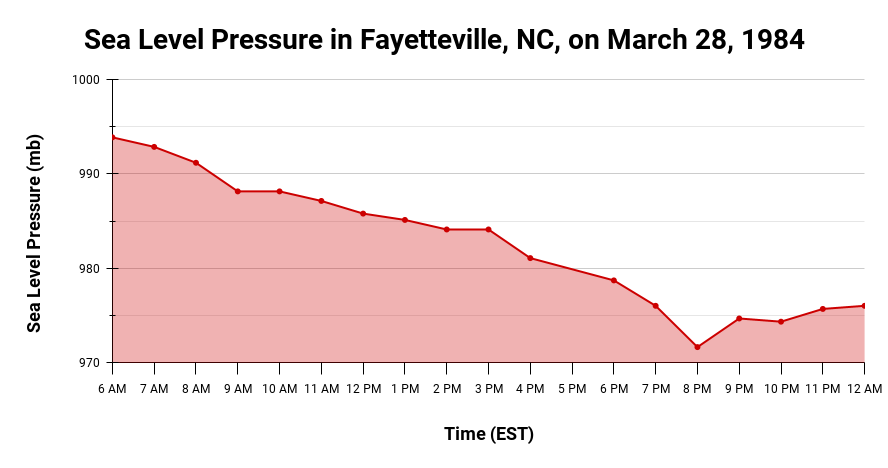

At the heart of this event was a deepening area of low pressure tracking in from the west. Just before the outbreak began, the minimum pressure near Athens, GA, dropped to 976 millibars – equivalent to a Category-2 hurricane bearing down on the Carolinas.

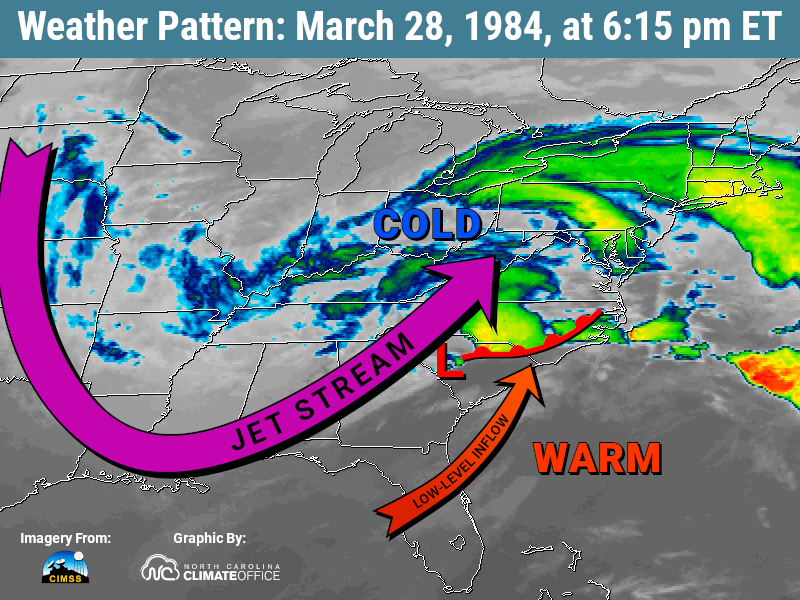

The storms set up along a warm frontal boundary that extended from the low pressure center into eastern North Carolina, and separated two vastly different air masses. To the northwest was chilly, Canadian air, where temperatures had been in the 20s and 30s on the morning of the outbreak. To the south and east was a tropical, humid air mass, which warmed well into the 70s and even the low 80s just hours before the outbreak began.

A broad trough in the jet stream stretching from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf coast was also approaching, and as that cold air moved in at the upper levels of the atmosphere, it ramped up the instability even further.

It was only a matter of time before that warm air near the ground began to rise rapidly through the cooler air above it, kicking off thunderstorm development. And those storms were set up to be sustained and severe.

One measure of atmospheric instability, called the Convective Available Potential Energy or CAPE, showed astronomical values of around 3,000 Joules per kilogram across the eastern Carolinas, representing almost unlimited fuel for storms once they formed.

Brisk southwesterly winds at low levels would keep those storms tracking along the warm front, which would provide an ongoing lifting mechanism to take advantage of that instability.

In addition, the counterclockwise circulation around the low pressure center induced a strong southerly flow into eastern North Carolina. That brought in even more warm, humid air to fuel the already unstable air mass.

And because of the high wind speeds and changing wind direction in the lowest mile of the atmosphere, intense wind shear was present, which would provide the rotation needed for tornadoes to form.

In combination, those ingredients meant the stage was set for long-lasting supercell thunderstorms fueled by strong, rotating updrafts that could support wide and intense tornadoes, the likes of which North Carolina hadn’t seen in generations.

Timeline of the Tornadoes

The 1980s was not the most advanced period for weather prediction. Computer model forecasting was still in its infancy, and until the introduction of the NEXRAD network in 1988, the National Weather Service used much older radar equipment built on World War II-era technology, which lacked the velocity data that helps track the rotation at the heart of tornadoes.

But despite being in a comparatively more primitive era, all signs pointed to the potential for an active day in the lead-up to March 28, 1984. The previous evening, despite some uncertainty about exactly where the warm front might set up, the forecast discussion from the Raleigh NWS office assessed they “expect we will have [a] busy time tomorrow and tomorrow night.”

On the morning of the event, the NWS Severe Local Storms Unit – the predecessor of the modern Storm Prediction Center – included the Carolinas in a High Risk of severe weather, its highest of five threat levels.

The first severe thunderstorms of the afternoon fired up around 2:30 pm in northern Georgia. They continued popping up in South Carolina, including the first of that day’s seven F-4 tornadoes that spawned around 5 pm just north of Columbia.

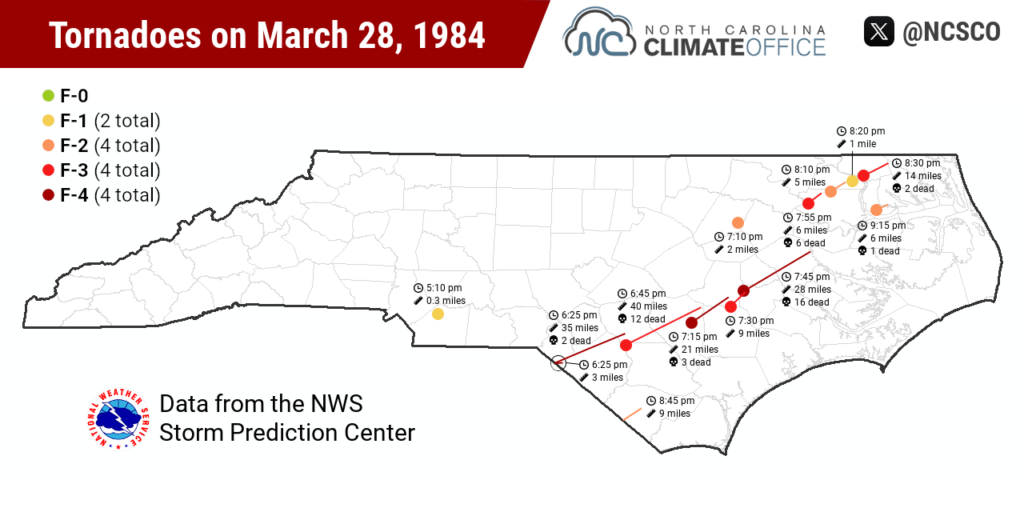

Around 6:25 pm, a pair of F-4 tornadoes crossed the state line into Scotland County. One lifted after just three miles, but the other stayed on the ground for an additional 35 miles, hitting the towns of Maxton and Red Springs.

Amid a path up to 2.5 miles wide, “every substantial building in Red Springs sustained F-1 or F-2 damage,” noted renowned tornado researcher Dr. Theodore Fujita, who visited to survey the area and investigate the family of tornadoes responsible for the outbreak.

At 6:44 pm, an F-3 tornado touched down in northern Bladen County and continued for 40 miles into Cumberland and Sampson counties, tearing through towns such as Beaver Dam and Salemburg with a dozen fatalities along the way.

In Roseboro, resident Carmen Faircloth told the Wilmington Morning Star that “it seemed like a lifetime but it was really just a minute or two” for the tornado – traveling at almost 60 miles per hour – to turn his house into rubble.

Another F-4 tornado spawned just north of Clinton by 7:15 pm, and its 21-mile track went through the towns of Faison, Calypso, and Mount Olive, where “it looked like we had been hit by a bomb,” according to Keith Evans from Carolina Power & Light.

Near sundown, when many springtime storms begin to fizzle out, the temperature difference fueling the instability was still apparent. By 7 pm, Greensboro had fallen to 45°F, while Kinston remained at 70°F, and was the next area in the path of the approaching storms.

Just after 7:30 pm, one F-3 tornado in Lenoir County ripped through La Grange, causing 81 injuries, and an F-4 touched down there and continued northeastward for 28 miles into Pitt County, killing 16 people. In Greenville, the tornado tore through houses and mobile homes until “there’s nothing left,” fire rescue chief Tony Brannon told The East Carolinian.

The rest of the evening saw a cluster of six tornadoes in northeastern North Carolina between Rocky Mount and the Great Dismal Swamp, rated between F-1 and F-3 intensity. Each could have been a headliner for almost any other severe weather event, but on this day, they were simply the dramatic and destructive aftershocks following an afternoon of nearly continuous tornado terror.

Still a Record-Holder

In total, 14 tornadoes were on the ground in the state that day, including four at F-4 strength over a frantic two hours that evening. The devastation they left behind was massive. Total property damage in the Carolinas amounted to at least $578 million, with 57 fatalities. Of those, 42 occurred in North Carolina, along with at least 800 injuries.

Governor Jim Hunt said it was “the worst natural disaster we’ve had in a hundred years in North Carolina.” While the mountain floods of July 1916 were deadlier, with an estimated 80 fatalities, and Hurricane Hazel’s winds covered a wider area, it’s also hard to argue that the governor’s words were hyperbole. Few events had flattened entire communities in an instant like the 1984 tornadoes did.

Perhaps the only prior severe weather event in the same ballpark was the so-called Enigma outbreak a century earlier on February 19, 1884. On that date, at least 9 tornadoes affected North Carolina, including an F-4 in Rockingham County that killed 23 people.

Over the past 40 years, we’ve rarely, if ever, seen the same power unleashed by Mother Nature as on March 28, 1984. The High Risk designation has only been used in eastern North Carolina four times since then.

In a bit of tragic irony, one such case was on March 27, 1994 – ten years almost to the day after the 1984 event – during the Palm Sunday outbreak that saw another round of deadly, long-lived tornadoes extending into North Carolina.

Our last High Risk event was on April 16, 2011, which featured a record-setting 30 tornadoes in a single day. But among North Carolina’s other tornado records, the March 28, 1984, outbreak dominates.

That single day featured 4 of the 12 F-4 tornadoes in North Carolina in the Storm Prediction Center’s modern records since 1950, and the most in one event. Its 42 fatalities are the most in a single day from a tornado outbreak. And with average path widths from 0.8 miles to 1.5 miles, our top four widest tornadoes on record happened in this event.

That’s a further testament to the incredible combination of ingredients that came together over North Carolina to support the sort of wide, violent tornadoes more typical of the Plains and the Deep South.

While it may lack the name recognition of a hurricane or the detailed data and social media accounting of more modern events, the Carolinas tornado outbreak on March 28, 1984, is in a league of its own among our severe weather events, and among the most destructive weather days in our state’s history.

On the cusp of a new severe weather season in 2024, lessons from 1984 still apply: namely, that waiting until a tornado warning is issued is too late to start preparations. Guidelines from the National Weather Service can help you and your family be ready to act if and when storms threaten.

Severe storms can and do happen every year in North Carolina, and as the March 1984 outbreak showed vividly and tragically, they may only take an instant to leave scars — on towns, homes, and families — that last a lifetime.

For more on this event, view the recaps from NWS Wilmington, NWS Morehead City, and NWS Raleigh.