Thirty years ago, Hurricane Hugo tested nearly every aspect of our infrastructure in the Carolinas.

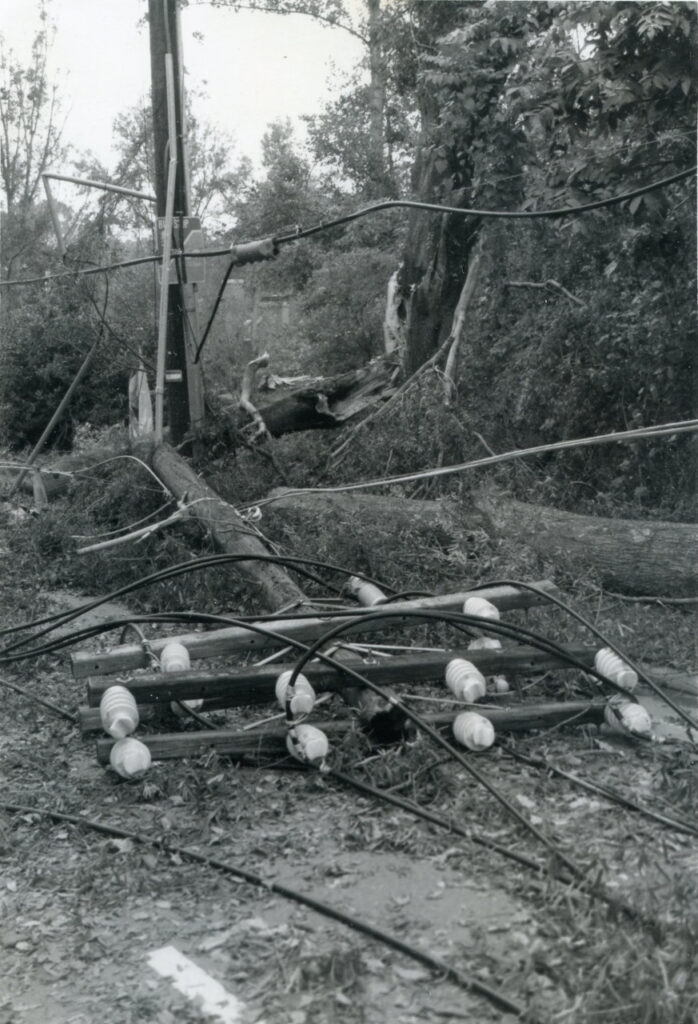

Trees and power lines snapped in the storm’s winds, cutting off the electricity that powered everything from water pumps to gas pumps. At the coast, roads and boardwalks were scoured away by the storm surge. Flash flooding in the Mountains inundated roads, nursing homes, and even a prison.

Although they’re not exactly wardens, Duke Energy’s employees in North and South Carolina are effectively the caretakers for much of the region’s population-sustaining resources, from the electrical grid to the water supply stored in large reservoirs.

And despite the storm’s fierce conditions, Duke’s key staff still had to work during Hugo, no matter the rain nor wind nor dark of night.

“The Longest Mile and a Half of My Life”

One such dutiful worker was Don Ligon. Now a manager of Duke’s Regulated Renewables Operations Center, he has been with the company for the past 43 years. During Hugo, he was an operator at the Lake Wylie Hydro Station southwest of Charlotte.

As Ligon finished his eight-hour shift ending at midnight — the same time as Hugo was making landfall near Charleston almost 200 miles away — the weather outside was fairly calm so he headed home.

Two hours later, he got a call from the operator who had taken over for him. The rain and wind had picked up, and the generators at the dam were surging.

Ligon went back to provide relief, but the 10-mile trip was far from easy. While southern Mecklenburg County is fairly developed now, in 1989, his commute was mostly back roads through wooded areas.

“When you get off these river roads going to the dam, they’re very isolated,” said Ligon.

A mile and a half from the dam, the road was blocked by a fallen tree. Ligon parked and started hiking the rest of the way — a trip that took three hours as the winds picked up even more.

“The longest mile and a half of my life,” he said. “You couldn’t see because the rain was blowing in your face. I’d have to stop at times to find shelter in the underpinnings of trailers, then climb over trees, under trees, watch out for downed trees.

“Is a tree going to fall on you? Are you going to step on a power line?”

At times, his trip was illuminated only by flashes in the distance, possibly from arcing transformers. There was an “eerie sound,” said Ligon, “and the sky turned almost green-looking”.

He finally made it to the dam, and as the sun came up, the damage toll was becoming apparent. The strong winds had wrenched off the tops of trees like a corkscrew, and many trees were fallen altogether.

“Just devastation,” recalled Ligon. “Mobile homes were crushed, trees and power lines were down.”

The hydro station continued generating power during the storm, but there wasn’t much demand because of the widespread outages. More than 90% of customers in Mecklenburg County lost power during Hugo, some for up to three weeks because of downed trees, impassable roads, and damage to the transmission system.

“Bang, Bang, Bang”

Nick Keener has been Duke’s director of meteorology since 1981, and during Hugo, he was working at the McGuire Nuclear Station at Lake Norman. As part of his duties with forecasting electrical distribution and crew scheduling, Keener was in communications with emergency planning staff in downtown Charlotte throughout the event.

Leading up to the storm, Keener said it was clear that Hugo could be significant for the Charlotte area.

“We hadn’t seen a storm like that before,” said Keener. “We actually were thinking it could be very bad for Charlotte because of the track and the speed, so we were planning for a lot of power outages.”

The McGuire facility was equipped with one instrument that he hoped might help track Hugo’s impact. Duke had been working with SUNY Albany on the early development of the National Lightning Detection Network, and the station had a lightning detection sensor — a three-foot mesh dish mounted on cement blocks on the roof.

But even that high-tech tool was no match for Hugo. At the height of the storm, the metal dish just became another thing going bump in the night.

“At 4 or 5 am, we started hearing a ‘bang, bang, bang’,” said Keener. “The wind was rolling it around like a boulder.”

That wasn’t the only unusual impact from Hugo that stands out in Keener’s mind.

“I also remember stepping outside and feeling the rain as it pelted you. It was almost like needles hitting and raining horizontally.”

Hugo’s strong wind gusts, measured at 93 mph by an unofficial sensor near Lake Norman, made it look more like the open ocean.

“With what little light there was, you could see the waves wicking up,” said Keener.

The scenes — and smells — from after the storm stand out as well.

“Oak trees completely uprooted, snapped at mid-level, leaves completely removed from their trees and covering the ground,” he said. “Smoke from people charcoaling and grilling outside.”

It was a striking first-hand experience for a meteorologist amid the hurricane.

“Everything Was Just Like Matchsticks”

Hugo effectively put life on hold for Charlotte residents, littering their best-laid plans with some added inconvenience. Among them was Ed Bruce, the lead engineer for Duke Energy’s Water Strategy and Hydro Licensing Group for the past 39 years.

Bruce and his wife lived in Charlotte and were preparing to move across town, with a scheduled closing date on their new home just two days after Hugo hit.

Before that, Bruce wondered if he’d even have a house left to sell as the storm came through.

“It basically sounded like a train on a track for about four straight hours of just non-stop roaring,” he said. “You couldn’t sleep or anything. You were just sitting there going, ‘is this house going to get blown over?'”

Both homes fortunately avoided major damage, but much of the Charlotte area wasn’t as lucky.

“No matter where you drove, everything was just like matchsticks,” said Bruce. “It was like a tornado hit, except it was everywhere. Roads blocked, big trees down.”

Even basic tasks like making phone calls were complicated by the storm.

“I recall having to go to the mall to use a payphone to call the realtor and closing attorney to find out when we would close, and how to handle storm damage to each house,” said Bruce. “A real mess for me.”

Bruce noted that the scale of the cleanup may have been as extensive or even more so in Charlotte than it was for coastal South Carolina, where Hugo made landfall.

“As bad it was in Charleston, they had smaller pine trees,” he said. “Those are easier to clean up than an oak tree. There’s no comparison to the size of the trunks and the weight of the trees.”

For Bruce and his wife, moving day still came as expected, and despite the power still being out, trees still blocking roads, and rain falling from an event after Hugo, they found that the storm couldn’t delay everything in Charlotte.

“The movers showed up right on time and we were like, ‘you’ve got to be kidding’,” he said.

Lessons Learned for Duke

The direct impact on the Carolinas by Hurricane Hugo included a heavy hit for Duke Energy.

“Hugo was a tremendous cost to our company, both from cleanup and restoration,” said Bruce.

But the storm also showed opportunities for improvement.

“They learned a lot of lessons about what people wanted to know about power restoration, and I think they took some of those lessons relative to communication with customers forward into the next few years, when we had a bunch of ice storms,” Bruce added.

On the forecasting side, the experience from Hugo — along with better computing power in the 1990s — helped Duke become more sophisticated with their pre-storm planning.

“We’ll plan an event four, five, six days out once we identify a risk,” said Keener.

Duke’s forecasts can now predict how many customers will lose power during a storm, which can ensure they have adequate resources such as internal and external crews on call.

Technology has helped make for a smarter infrastructure, but the associated creature comforts have also added impatience when Duke’s customers lose power.

“We have much better systems in terms of folks being able to identify that their power is out. They can automatically let us know and we can text back when the power is restored,” said Keener. “Now, our call centers can tell you people get very annoyed if their power is out for more than two or three hours.”

While the western Piedmont has endured a number of ice storms, severe weather events, and even tropical systems such as Florence and Michael in the past 30 years, the Duke employees who went through Hugo all agree that there is simply no comparison with the 1989 hurricane.

“It’s not even in the same zip code. It was ten times worse,” said Bruce. “The sheer number of trees down on power lines, blocking roads, having the need to call in the National Guard since on major roads, there were no working traffic lights.”

From long late-night walks under a green sky to the lake that looked like an ocean to red-clay craters left by uprooted oaks, there are some unforgettable, unbelievable memories associated with the last hurricane to hit Charlotte.

Special thanks to Don Ligon, Nick Keener, Ed Bruce, and Chris Hamrick from Duke Energy for providing information and images for this post.

Sources:

- September 1989 Special Weather Summer from Climatological Data North Carolina

- Hurricane Hugo from the National Weather Service in Wilmington