Rapid Reaction: Severe Storms Spawn Tornadoes in NC

Earlier this week, a cold front moving across North Carolina produced strong thunderstorms that spawned six tornadoes, then left high, gusty winds in its wake. It was a particularly intense severe weather event for February or any month, for that matter.

Severe Weather Setup

This event had all the ingredients for a tornado outbreak that we discussed in our recap of the April 16, 2011, outbreak, so it naturally inspired comparisons to that event. The basic atmospheric setup was similar, and many of the severe weather indicators were the same or even more supportive of strong tornadoes.

Leading up to the event, an upper-level trough was crossing the Ohio Valley, and jet stream energy ahead of the trough supported a strong surface low. Such a strong low also meant a tight pressure gradient and high winds.

On Wednesday morning, cool air at the surface was replaced by warm, moist air surging northward out of the Gulf of Mexico. Although low clouds and light rain lingered through mid-day, the daytime heating brought clearing skies, rising temperatures, and increasing instability.

One measure of that instability — the Convective Available Potential Energy, or CAPE — jumped by 200 to 400 J/kg from noon to 3 pm. That extra upward “kick” for rising air would help fuel the strong storms that followed.

As the atmosphere became primed for severe weather in eastern North Carolina, a line of storms associated with a strong cold front crossed the western Piedmont, where a handful of severe thunderstorm warnings were issued.

That line then moved into a more favorable environment for tornado development. Wind shear in the lowest 6 kilometers, or about 4 miles, of the atmosphere exceeded 90 knots (104 mph) in some spots. That compares with 60 to 70 knots of wind shear in the April 2011 event.

Although wind shear can tear apart developing storms, when a source of intense lift — in this case, a cold front — is present, some of the storm cells can overcome that high shear. When that happens, only the strongest storms in the line survive, and they become discrete supercell thunderstorms capable of producing tornadoes.

The roaring southerly wind that contributed to the strong wind shear also gave high storm-relative helicity — a measure of air spiralling horizontally near the surface. Tornadoes can form when such high-helicity air is tilted vertically by strong updrafts, which the supercells had in spades. Helicity values were extremely high, exceeding 600 meters² per second², which was comparable to the April 2011 event.

Statewide Tornadoes

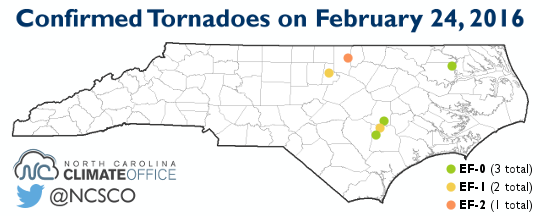

National Weather Service offices around the state confirmed six tornadoes as part of this event.

Before the line of supercells reached eastern North Carolina, storms ahead of the cold front spawned a pair of tornadoes in Duplin County and one in Wayne County around 1 pm.

The NWS Wilmington confirmed an EF0 tornado briefly touched down in Warsaw, with estimated winds of 80 mph. Storm reports from the area note snapped trees and downed limbs.

Also in Duplin County, an EF1 tornado was briefly on the ground east of Calypso. The tornado’s winds, estimated at 100 mph, snapped off eight power poles and blew the roof off of a mobile home.

Just north of there, an EF0 tornado with maximum winds of 75 mph was confirmed in Wayne County near Seven Springs. Reports from the area indicate damage to trailers and farm buildings.

In northeastern North Carolina, an EF0 tornado with winds of 60 to 65 mph briefly touched down just before 3 pm near Colerain in Bertie County. The NWS Wakefield reported minor damage to trees and small structures over a half-mile path.

When the line of supercells began to form, one of the first cells to develop downed trees in Durham County and briefly spawned an EF1 tornado in a forested area north of downtown Durham around 4 pm. Maximum winds were estimated at 90 mph.

That supercell later spawned an EF2 tornado in Granville County near the Oxford-Henderson Airport. The NWS Raleigh reports that the tornado was on the ground for five miles before lifting in far western Vance County, with maximum winds of 125 mph.

Once the storms were past, we were left with high winds of 40+ mph that caused power outages across the state. Mount Mitchell reported gusts of up to 68 mph. The Monroe Airport had a gust of 60 mph, and Rockingham and Siler City both reported gusts of 58 mph.

Although it was an active weather day across the state, no deaths or injuries have been reported in North Carolina.

Other February Outbreaks

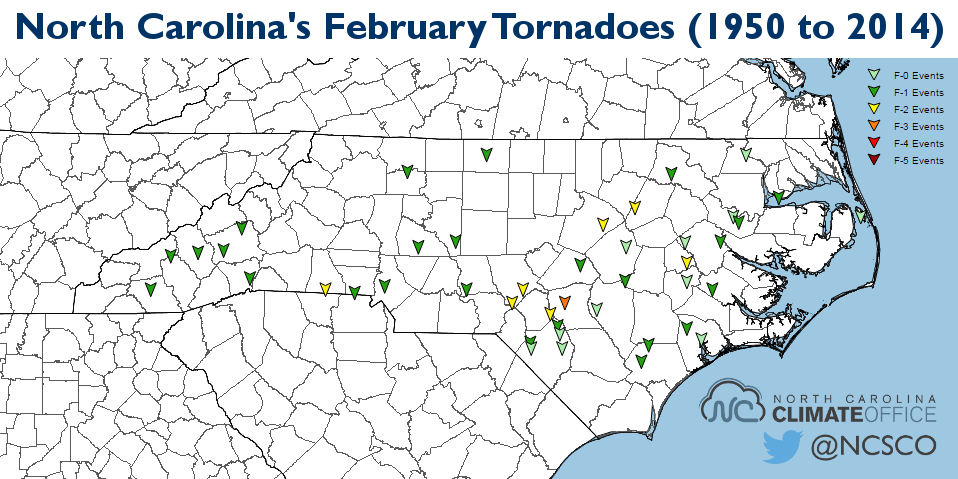

Appropriately enough, earlier this week we discussed North Carolina’s February tornado climatology and the F3 tornado that ripped through northern Fayetteville in 1971. While that tornado was the only one in North Carolina associated with the Southeast US outbreak, historical February outbreaks have caused strong tornadoes all across the state.

From 1950 to 2014, North Carolina had 45 tornadoes in the month of February. The F3 in Fayetteville stands out as the strongest, but every part of the state — from Macon County in the Mountains to Manteo along the coast — saw February tornadoes during this period.

Those mountain tornadoes occurred on February 18, 1976. Two injuries were reported in Rockingham County, and the seven F1 tornadoes caused over $1.5 million in damage.

In central North Carolina, a notable outbreak of five F2 tornadoes happened on February 11, 1981. Those twisters caused a death in Hoke County, as well as two injuries and $6 million in damage.

More recently, three tornadoes hit the central coast on February 18, 2008, including an EF2 in Greene County that caused three injuries.

With six confirmed tornadoes, this week’s event will certainly go down as one of our most active February outbreaks, and the pattern that yielded such an event is one of the most impressive you’ll see any time of year.

- Categories: