This is the third part of our weeklong blog post series Century Since the Storm.

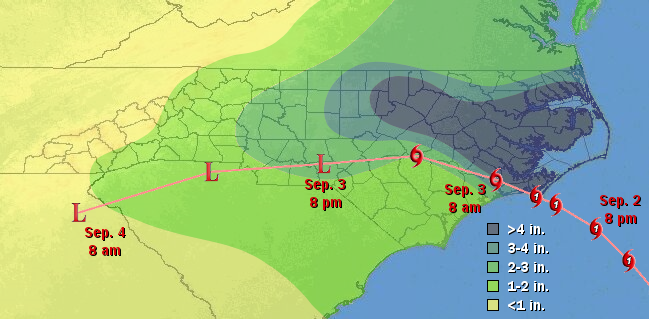

Early on the morning of September 3rd, 1913, just before 4 a.m., the storm made landfall as a category 1 hurricane near Cape Lookout. The worst damage along the Outer Banks occurred north of Cape Lookout, which was within the storm’s right-front quadrant — the region where the forward motion coupled with the hurricane-force winds tends to sharpen the hurricane’s impact.

At Cape Hatteras, 74 mph winds were recorded, and telegraph lines and wireless transmission stations were knocked out. This meant damage reports were limited at first, often based on speculation and word-of-mouth. Two days after the storm’s landfall, newspapers reported “scenes of desolation” along the coast, and assumed the small, sea-level village of Ocracoke and its 500 residents were surely wiped away by the storm surge.

As news finally came in from the coast, it became clear that the damage along the Outer Banks, while significant, had been exaggerated. On September 6th, newspapers such as the Evening Independent in St. Petersburg, FL, gave a more accurate report of the damage in Ocracoke:

Several houses were overturned, many small boats were washed away and some cattle were drowned but not a life was lost. The houses on Oracoke [sic] are built on top of piling to protect them from the frequent high tides.

However, locations further inland could not escape so easily from the storm tide. As the storm moved over the shallow Pamlico Sound, its winds whipped up the waves and its forward motion pushed that water westward, funneling it up the narrow Roanoke, Tar-Pamlico and Neuse River basins. That water eventually spilled into towns including Washington, Bayboro and New Bern, causing severe damage — reports said “buildings crumpled”, “streets were inundated”, and “thoroughfares were lined with debris”.

In Washington, perched precariously along the Pamlico River, the 10-foot flood levels from 1913 storm remain a record today. Eyewitness accounts recorded in the Washington Daily News paint a vivid picture of the damage in the town. The water rushed in, knocking out bridges and carrying away homes and boats. Where buildings remained, so did the flood waters. But as the storm moved further inland on the 3rd, much of the water receded, uncovering the scenes of damage and destruction left behind.

The water receding back into the Pamlico Sound meant one last problem for the Outer Banks. This time, instead of water surging in from the ocean side of the islands, it came in from the sound side, like water sloshing back and forth in a bathtub, causing additional flooding in those already rattled areas.

For the rest of the state, the main impact from the storm was the rain it brought. The heaviest accumulations came across the central coastal plain, with that swath following the path of the storm’s right-front quadrant. Even inland locations like Rocky Mount and Durham received more than five inches of rain from the storm as its remnants tracked across the southern part of the state.

Today, few reminders of this storm remain. Time, with a little help from human ingenuity, has largely healed the wounds from 100 years ago. But in recent years, one relic from this hurricane has occasionally been uncovered by the shifting sands on Ocracoke’s beach. The video below tells the story of the wreck and rescue of the George W. Wells.

Sources:

- Champagne Democrat from Sep. 5, 1913

- Miami Daily Metropolis from Sep. 5, 1913

- Evening Independent from Sep. 6, 1913

- The Wreck of the George W. Wells from the Village Craftsmen