January brought a rare run of cold weather that supported several rounds of snow. But with little other precipitation, drought continued expanding across the state last month.

A Frigid First Month in 2025

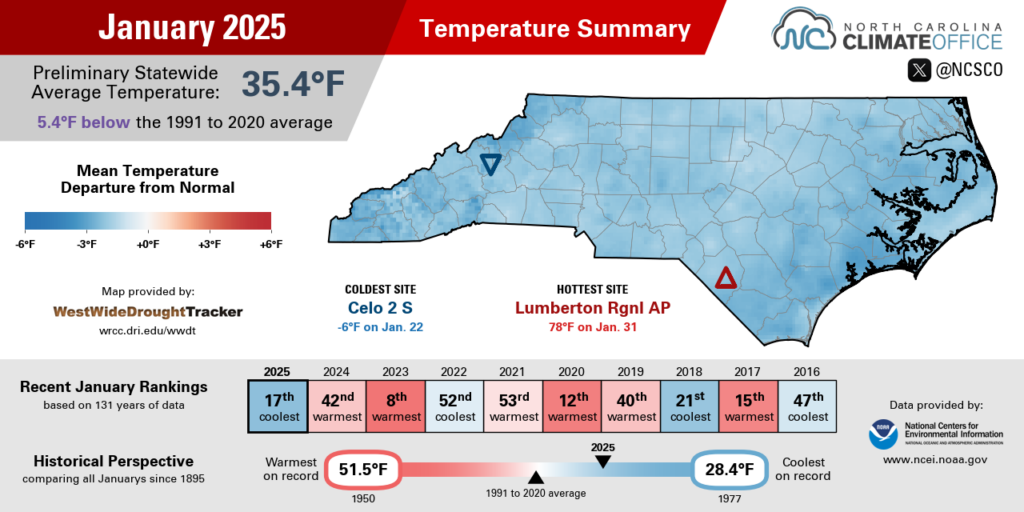

A deep chill set in for several weeks in January, yielding one of our coldest months in recent memory. Based on preliminary data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), the average temperature of 35.4°F ranked as our 17th-coolest January dating back to 1895 in North Carolina.

Statewide, it was our first month with below-average temperatures since June 2023, and our first cooler-than-normal January since 2022, which was also the last snowy month for most of the state.

At the heart of the chill for much of the month was a deep trough in the jet stream over the US and a series of Arctic high pressure systems diving southward across our region. It produced the sort of sustained cold we rarely see, even in the heart of our winter season.

To that end, it ranked as the 7th-coolest January for Wilmington, and the coolest there since 2011. Cullowhee (8th-coolest), Morganton (9th-coolest), and Greenville (10th-coolest) also finished with one of their top ten coolest Januarys on record.

The major metropolitan sites across the Piedmont were each cooler than normal in January, but not as extreme as on either end of the state. Greensboro had its 19th-coolest January on record, Charlotte tied for its 31st-coolest, and Raleigh tied for its 42nd-coolest January since 1887.

In addition to more extreme rankings, parts of the Mountains and Coastal Plain also had more extreme cold temperatures as a bitter cold air mass built in. Morning lows in some high-elevation areas dipped below zero on January 22, including -4°F in Banner Elk and -5°F on Mount Mitchell.

At the coast, with a blanket of snow on the ground, low temperatures on January 23 dropped down to 6°F in Mount Olive, 8°F in Louisburg, and 9°F in Lewiston – the first single-digit reading at all locations since early January 2018.

Before the month ended, we did manage a few chill-breaking days with some spring-like warmth. On January 29, high temperatures hit 72°F in both Lincolnton and Raleigh, with more widespread 70s across the western Piedmont on January 30.

Across eastern North Carolina, the mercury climbed as high as 78°F in Lumberton on January 31 — a massive turnaround just over a week after temperatures bottomed out at 13°F on January 23.

A Little Snow, But Limited Precipitation

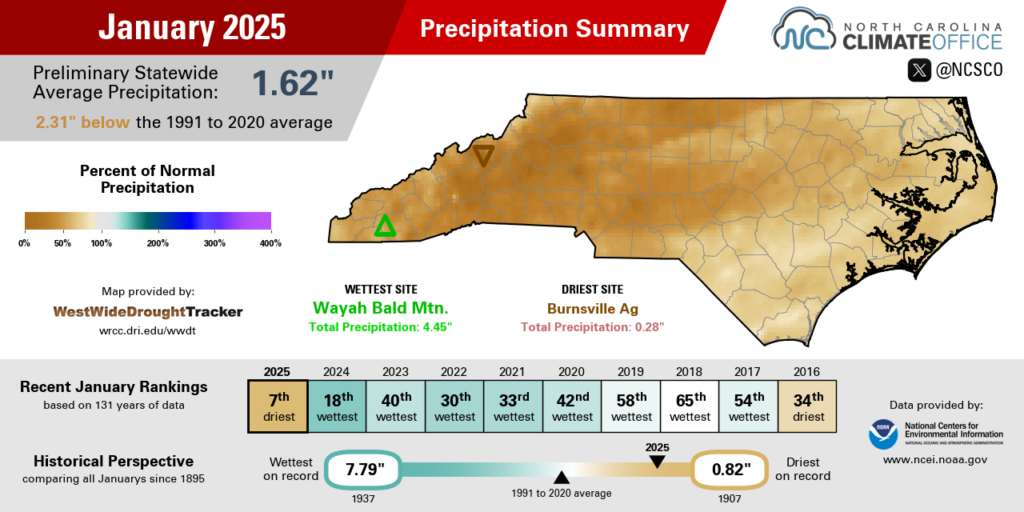

Despite multiple wintry events, liquid precipitation was limited last month, making it one of our driest Januarys on record. NCEI reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 1.62 inches, which ranks as the 7th-driest January in the past 131 years.

With only about a third of our normal monthly precipitation, this broke a string of six consecutive wetter-than-normal Januarys in North Carolina. Our only drier Januarys historically occurred in 1907, 1981, and 1927.

Much of western North Carolina finished with one of its top ten driest Januarys on record, including the 10th-driest in Marion, the 7th-driest in Hickory, and the 3rd-driest in Highlands dating back 118 years.

In eastern North Carolina, it ranked as the 19th-driest January for Raleigh, the 20th-driest in Fayetteville, and the 10th-driest in Elizabeth City. Each site had less than two inches of total precipitation for the month.

Those low totals and dry rankings were the result of just three to four precipitation events in most areas, including the two mid-month wintry events in the west on January 10-11 and in the east on January 21-22. The month was otherwise bookended by rain during frontal passages on January 6 and 31, although totals generally came in at under an inch from each event.

Of course, it may seem odd to talk about dry weather given that many areas had their greatest monthly snowfall in several years. For example, the 7 inches in Reelsboro was the most snow in a month since February 2014, and the 8 inches on Cedar Island was its most since January 2003.

But with snow, a little liquid goes a long way. For instance, the 4.2 inches of snow in Plymouth on January 22 came from just 0.20 inches of liquid precipitation, which is well below the weekly average of 0.89 inches.

That made it possible for a solid snow to cover the ground even as another week went by with below-normal precipitation. And those dry weeks have been the norm since last fall. In areas such as Greenville and Wilmington, 15 out of 18 weeks since October have been drier than normal. That has helped drought conditions spread across almost the entire state this winter.

Winter Drought Degrades

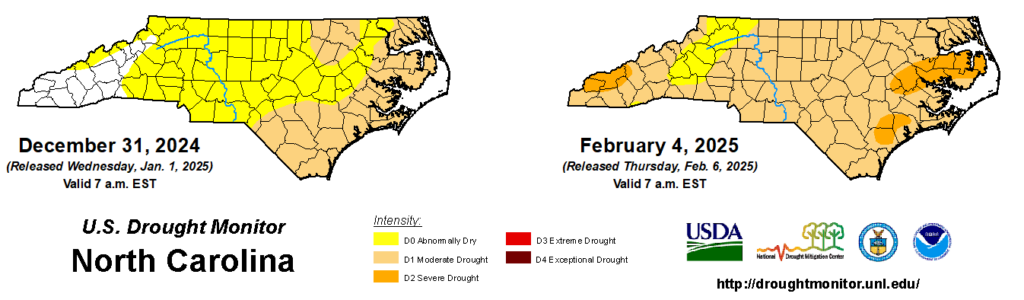

In our winter outlook, we noted this would be a decisive season for droughts, and in January, that proved to be true. After statewide snow coverage last month, our snow droughts were reset to zero, but we can’t say the same thing for our meteorological drought, which has continued to expand and degrade.

That in itself was a rare event for the winter, which is usually a season of drought recovery. Instead, as Severe Drought (D2) emerged across parts of the Coastal Plain last month, it marked the greatest wintertime expansion of D2 or worse since February 1, 2011, and the biggest ever January increase in D2 coverage since the US Drought Monitor began in 2000.

The current drought took root last fall, when our weather took an abrupt dry turn in October following Hurricane Helene. Over the past four months, precipitation deficits have steadily increased and now stand at 6 to 8 inches across much of the state, and as much as 10 inches along parts of the coastline.

While impacts were at first slow to appear alongside lingering flood damage and after the fall harvest was completed, they’ve become more prominent this winter seemingly everywhere except at the ground’s surface, where the cooler temperatures and recent snow have helped tamp down signs of dryness.

We see those impacts elsewhere, though. Streamflow levels have fallen below normal statewide, which has also reduced reservoir inflows. For now, most major lakes are holding near their seasonal targets, but they’ve built little to no buffer going into the spring.

Deeper soil moisture levels are also running below normal in eastern North Carolina, and groundwater wells have also struggled to make any recovery in recent months.

Wildfires have also been burning across parts of western North Carolina in recent weeks, including multiple blazes in McDowell County. Last week, the Crooked Creek fire burned 220 acres and prompted local evacuations near Old Fort, while the North Fork fire remains active after burning more than 600 acres.

Even if drought isn’t apparent in your own backyard now, the concern is that a few weeks of warmer weather would suddenly cause impacts to explode across the landscape as any topsoil moisture evaporates and dry vegetation becomes a powder keg for a potential spring fire season.