It’s a tradition as old as nature itself — the changing leaf colors that put a pop in our picturesque fall landscapes.

Trees often look like they’re completely in sync as they simultaneously change to shades of yellow, orange, and red, but each tree is operating independently and using everything from its genetics to the weather to its home state to tell it when to turn.

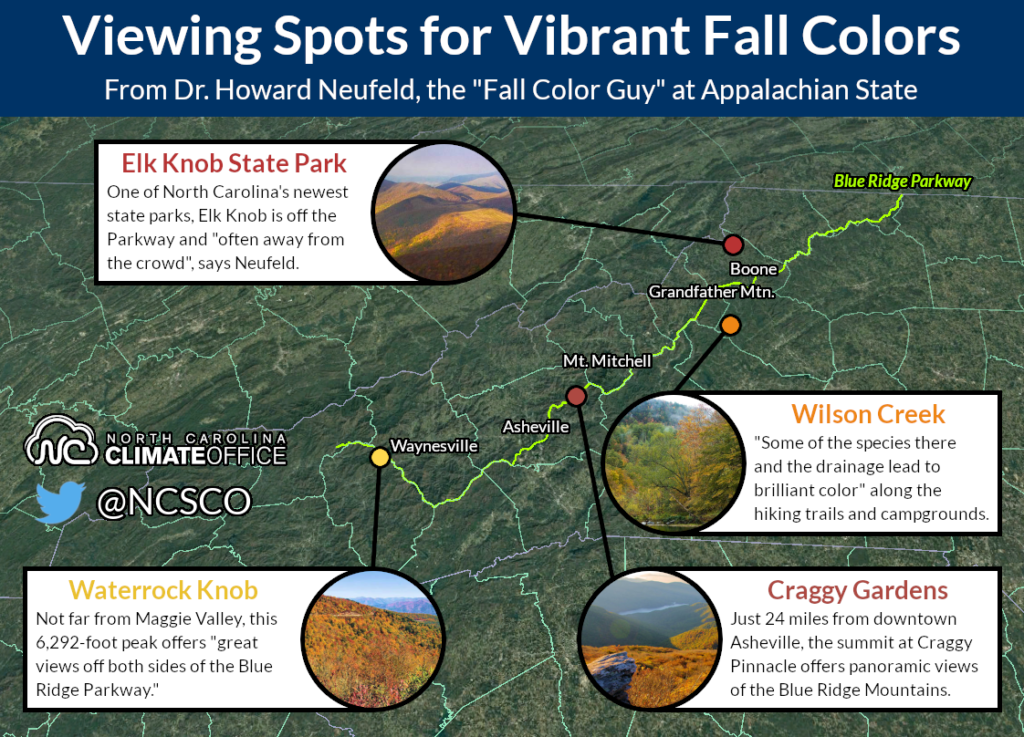

Few people in our state know more about what makes trees tick than Dr. Howard Neufeld, a professor of biology at Appalachian State University. To his thousands of followers on Facebook and his website, Neufeld is better known as the “Fall Color Guy” because of the weekly updates he shares this time of the year.

Neufeld issued his first report about eleven years ago, and while he no longer works with the state board of tourism to provide official updates — that job is now handled by park rangers spread across North Carolina — he enjoyed it so much that he’s now “an independent Fall Color Guy,” he said.

Neufeld recently shared some of the science surrounding leaf color with us, including the biology and weather influences from temperature and precipitation. He also told us when the peak of the season typically occurs, and what the outlook shows for this fall.

It’s in Their Genes

According to Neufeld, North Carolina hasn’t always had the same variety and vibrancy of fall color.

“Your great-grandparents probably saw very different fall color around here because when they grew up, the predominant tree was the chestnut,” he said.

After the chestnut blight wiped out most of those trees in the first half of the 20th century, the chestnuts — whose leaves turn a bright yellow — were replaced by different species such as hickory, oak, and maple trees, which tend to be more colorful.

Each tree makes its color very differently, depending on its species’ biology.

Yellow leaves contain pigments called xanthophylls, while orange leaves include a similar pigment called carotene — the same one that gives carrots their distinctive color.

As Neufeld explained, both of these pigments are produced in the spring but have to wait until the fall for their opportunity to shine.

“Those pigments are there all summer but you can’t see them because they’re covered up by the chlorophyll,” said Neufeld.

While the green chlorophyll pigments absorb solar energy to conduct photosynthesis and help the trees grow, the xanthophylls still serve a purpose. Known as accessory pigments, they help dissipate extra light energy so it doesn’t damage the trees.

Once the days become shorter and solar radiation decreases, the chlorophyll fades and the yellow and orange pigments remain.

Trees such as maples known for their bright red leaves use a different type of pigment, called anthocyanins.

“It’s the same pigment that makes roses red and blueberries blue,” said Neufeld.

Unlike xanthophylls, anthocyanins are produced beginning in the fall, and as chlorophyll degrades, the leaves change from green to red. This red pigment is like sunscreen for trees, as it prevents leaves from taking in too much sunlight.

“When it’s cold, all of the enzymatic processes in the leaves slow down,” said Neufeld.

That means excess light energy can’t be fully processed in the fall, which can affect the trees’ ability to move nutrients from the leaves to the twigs for wintertime storage.

For trees, these seasonal changes are coded in their DNA. But they still take some cues from Mother Nature, including the weather each year.

Temperature Triggers

Neufeld said leaf color is most sensitive to temperature. The ideal conditions for vibrant colors are sunny days and cool nights starting in mid-September.

Cool temperatures cause chlorophyll to degrade and the other pigments to emerge. For that reason, warmer falls can sometimes see a delay in the color change, typically by 3 to 5 days.

Cooler weather can make red colors in particular pop more. As the temperature decreases, the viscosity of the sap increases, making it tougher for water to move throughout the trees. That helps sugars build up in the leaves, which triggers the production of more anthocyanins.

Those sugars also need photosynthesis to produce the red pigment, so sunny days help that process as well.

In extreme warm or cold temperatures, the fall color isn’t as good, as we saw last year — one of the worst seasons Neufeld has covered in his tenure as the Fall Color Guy.

During September 2018 — the 3rd-warmest September on record statewide — the higher temperatures increased the respiration rate in trees, so they burned off those sugars for energy and had duller colors.

In mid-October, the remnants of Hurricane Michael ushered in some cooler weather but also brought high winds, so any leaves that had changed colors dropped off the trees, giving a strange scene at the higher elevations.

“All the colored leaves fell off and it got green again,” said Neufeld. “It was like it went backwards in time.”

When nighttime temperatures dropped below freezing a few weeks later, those remaining leaves fell suddenly without changing color. It proved a point that seems to echo through the mountains among those who have seen decades of fall color.

“Old timers will tell you the best conditions for color are when it gets down near freezing but not to freezing,” said Neufeld.

Rain or Shine?

Precipitation tends to be less important for leaf color, but as with temperature, extremes can spoil the show.

If it’s too dry in the summer and trees are drought-stressed, they may drop their leaves to reduce the moisture demand and prevent excess transpiration from the large surface area of their leaves.

“How do you reduce that demand?” said Neufeld. “Drop off the oldest leaves because they’re the least active. It starts from the inside and works its way out.”

Leaves turning brown and falling early, especially on drought-sensitive species like tulip poplar and birch trees, are often signs of stress rather than the normal seasonal activity.

Wet weather in the early fall can also make a difference, but mainly because rainy days are cloudy ones.

“If the rainy weather persists into October, there’s less sun, less sugar production, and less red colors,” said Neufeld.

However, one misconception he often hears is that rainy weather will dilute the colors like watercolor paint.

“It may dull the colors, but it’s not diluting them,” he said. “The trees aren’t as making as many anthocyanins.”

Wet weather can also be windy weather, and Neufeld said that has ruined more than one fall for color in North Carolina.

“That’s the worst thing that can happen during the middle of fall,” he said. One year, he recalls, “the fall color season lasted two days” because of an ill-timed wind- and rainstorm at the peak of the season.

The Peak, Beginning at the Peaks

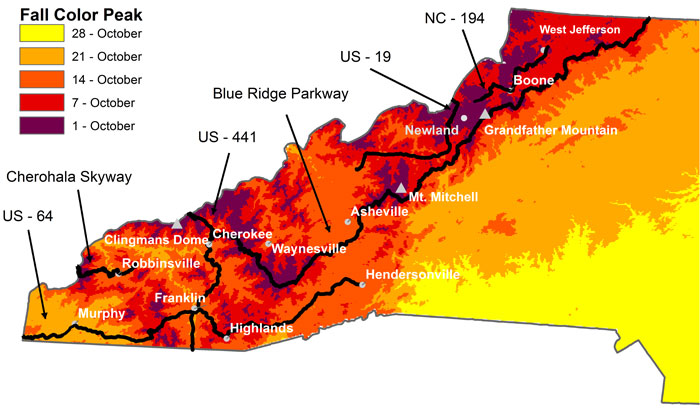

So when is the peak of our season? At the highest elevations such as mile-high Grandfather Mountain, leaves begin changing in late September.

In the Blowing Rock and Boone area, at an elevation of around 3,000 feet above sea level, the peak typically occurs between October 12 and 20.

After that, Neufeld offered a good rule of thumb for the color change in the rest of the state.

“Every 7 to 10 days, it drops about 1,000 feet,” he said. “By the end of October, you’re down in the 2,000-foot-or-so level like Asheville. In the Foothills and the Piedmont, you’re in the first week of November.”

The eastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain usually change by late November.

There can, of course, be local differences, particularly with what Neufeld calls “street trees”.

Many trees planted in urban and suburban areas were curated from other parts of the country, and if they came from colder climates, they may change color earlier than native trees even of the same species.

“When you bring a northern tree down to the south, it starts turning sooner,” said Neufeld, explaining that they’re using the photoperiod — or length of the day — as a bigger cue than the ambient temperatures.

Often, the most noticeable among those trees are red maples. A specific variety of that species, called “autumn glories”, were bred for fall color, and Neufeld said they seem to be what comes to mind when most people think of a spectacular season.

“I ask people what makes a good fall color year,” he said. “It’s always the bright reds.”

Conditions This Fall

Although our emerging drought entering fall 2019 has caused some leaves to turn brown and fall early, Neufeld said he’s still hopeful for good color this season. You may just have to wait a bit longer to see it, since our long-lasting summer heat could delay the peak by as much as a week.

True to that old-timers’ wisdom, several cooler nights in the Mountains so far this season have spurred along some trees to begin changing. Plenty of sunny days recently should help the colors pop on any leaves that don’t drop early due to the dry weather.

No matter the prevailing weather pattern, Neufeld said it’s almost a guarantee that parts of North Carolina will have spectacular fall color every year.

Our wide range of elevation, long leaf season, and variety of species make our state unique, which is one reason Neufeld said we draw in so many visitors each fall.

“You can have a six- to eight-week fall color season, while in New England, it’s two weeks,” he said.

According to his own estimate, Neufeld said tourists add at least $600 to $800 million to the economy of the Mountains every year to see the fall colors.

But in his mind, this time of year has a value beyond an economic one — in remedying what he calls “nature deficit disorder”.

“I also think it’s important philosophically,” he said. “It’s the one season that gets people to go outdoors more than any other season to appreciate the beauty of nature.”

While overcoming the pull of modern technology can be a challenge, Neufeld said that like the temperature teeter-totter on which picture-perfect leaf colors ride, there may be a happy balance between the two.

“Sometimes when I hike up Rough Ridge, people are all sitting up there talking on their cell phones. I’m sure they’re seeing nature even if they’re still on their phones.”