The calendar says it’s fall but it still feels like summer. Our September temperatures were warm, our precipitation was generally light after Hurricane Dorian, and drought is back in North Carolina.

Can’t Beat the Heat

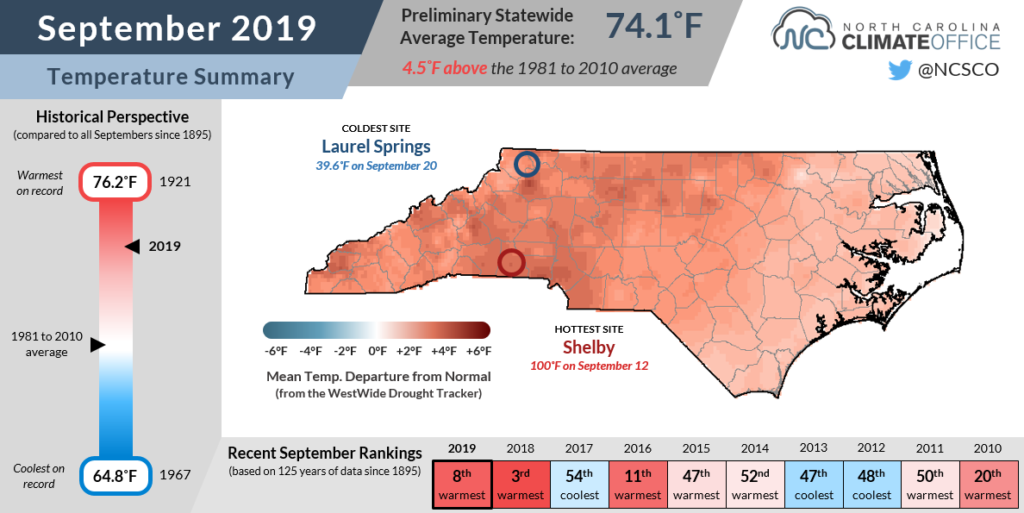

Summer-like temperatures have persisted well into the fall this year, making it one of our warmest Septembers in recent memory. The preliminary average statewide temperature of 74.1°F ranked as our 8th-warmest September out of the past 125 years.

For much of the month, our weather was dominated by high pressure sitting over the Carolinas. That gave us plenty of sunny days, but also a chance for the heat to build. In Charlotte, there were 22 days with highs reaching at least 90 degrees, which is tied for the most with September 1925.

Even Asheville reported 10 days with highs of 90°F or above, ranking as the most ever in September with one more 90-degree day than in 1925.

Based on average maximum and mean temperatures, it was one of the top-five warmest Septembers on record at many locations, including the warmest in Marion based on mean temperatures out of 108 years with data at that site.

Our only sustained relief from the heat came on September 18-20, when high pressure to our north funneled cooler air east of the Appalachians. On those days, our daytime highs dropped into the upper 70s and low 80s, near our normal temperatures for this time of the year.

For the month as a whole, average highs were up to 10 degrees above normal in Shelby — the hottest site in the state with a high temperature of 100°F on September 12 — and at least 5 degrees above normal across the western two-thirds of the state.

So when will that stubborn high pressure move and our heat finally dissipate? Not any time soon, according to most current forecasts. October is beginning with near-record highs in many areas, and the latest temperature outlook from the NWS Climate Prediction Center predicts another warm month ahead.

Dorian, Then Dry

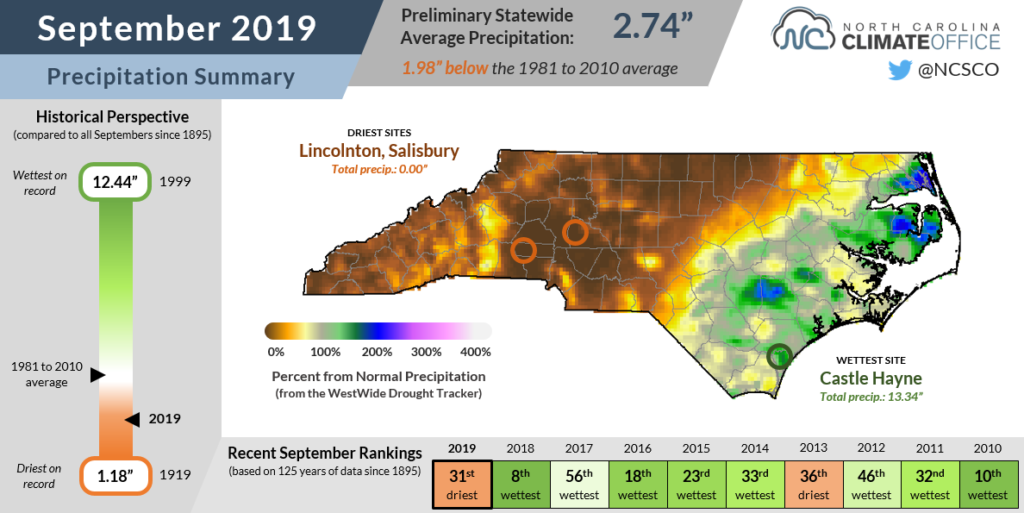

One year ago, our saturated state was still drying out after Hurricane Florence and one of our wettest Septembers ever. We had another landfalling hurricane this year, but it was still a dry month overall. The preliminary average precipitation of 2.74 inches was nearly 2 inches below normal, ranking as our 31st-driest September since 1895.

While Hurricane Dorian soaked the coast early in the month, that was the only significant widespread rain event in the state. Our ECONet station in Castle Hayne near Wilmington picked up 11.4 inches over three days during the hurricane and just 1.94 inches in the rest of the month.

Parts of the southern and western Piedmont didn’t see any rain at all in September. Lincolnton and Salisbury both reported no measurable rainfall, while Statesville received just 0.03 inches. Charlotte had 0.19 inches — tied for its 3rd-driest September on record, and the driest since 1961.

As with our temperatures, it was a pattern driven by high pressure blocking any storm systems from getting too close and suppressing afternoon showers and storms that we might otherwise expect in the summer-like heat.

Such dry weather this time of the year has some ominous historical connections. The last September this dry was in 2007, as the 2007-08 drought was approaching its peak intensity. September 1985 and 1986 were both dry as well during those drought years.

It’s not too surprising that a dry September is often associated with drought. As we’re seeing this year, dry Septembers are often hot ones as well, representing a continuation of summer and the stress that it creates on crops and water supplies.

In dry Septembers, we also often miss seeing rain from tropical systems during the climatological peak of hurricane season. At least parts of the coast received rain from Dorian this year. If not for that, the southeastern part of the state, which was already in Moderate Drought before the storm, could very well be the epicenter for the current drought.

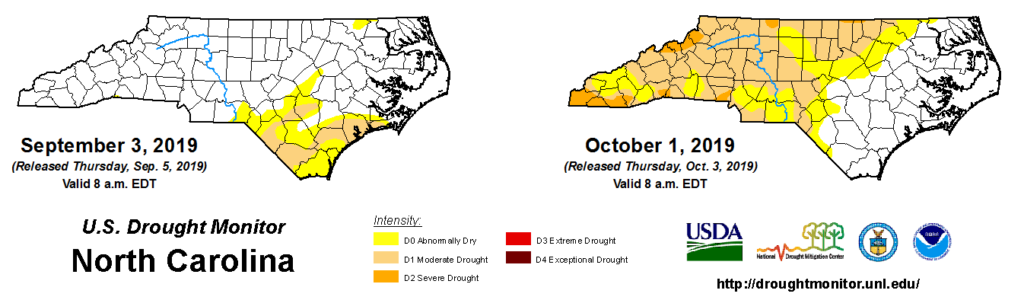

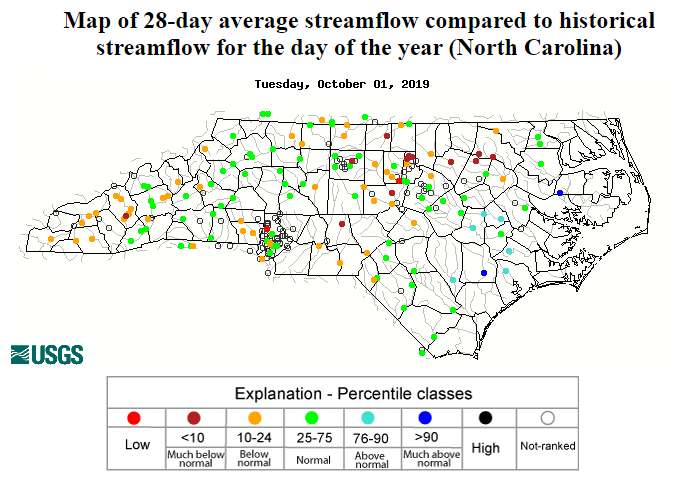

Facing a Flash Drought

As recently as three months ago, we were talking about how wet it was in the Mountains and northern Piedmont. Now, those same areas are seeing drought develop while they wish for rain to return.

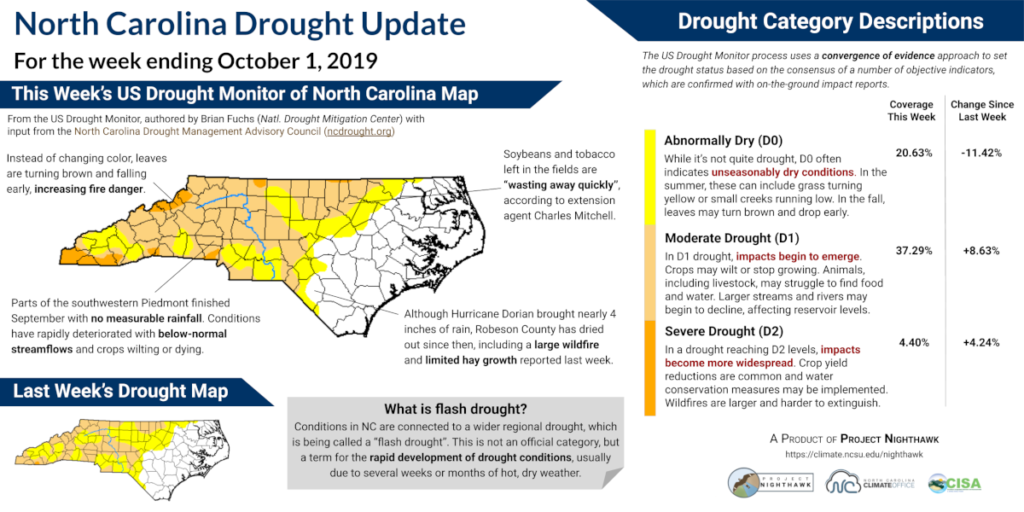

A fast-emerging drought like this one isn’t unheard of. In fact, it even has a name. Often called “flash drought”, it’s typically caused by a few weeks or months of hot, dry weather like we’ve had recently.

For agriculture, flash droughts can be impactful for several reasons. The sudden and sustained lack of rainfall can decrease crop productivity, especially if they were planted in a wetter period before the drought and developed shallower root systems.

While this fall’s drought emerged near or just after crops like corn and cotton were mostly harvested, others like soybeans, sweet potatoes, and peanuts are struggling to reach maturity as the end of the growing season approaches within the next month or so.

Farmers growing hay for livestock forage over the winter are also having trouble meeting that demand. In some cases, they may have to sell their animals if they can’t feed them all, meaning this drought — even if it’s a brief one — could have economic impacts felt years down the road.

For water supplies, a fall flash drought typically isn’t quite as bad as a summer one since many reservoirs are drawn down by a few feet to their wintertime elevations beginning in September. However, with dry weather from west to east, inflows fed by upstream rainfall may still be too low to fully recharge reservoirs along the major river basins.

This week, the US Army Corps of Engineers reported that Jordan Lake on the Cape Fear River, Falls Lake on the Neuse River, and John H. Kerr Reservoir on the Roanoke River were all 1.5 feet below their target levels.

Duke Energy reported that Lake Norman on the Catawba River was 2 feet low, and High Rock Lake on the Yadkin River is only about a half-foot above its normal minimum elevation, according to Cube Hydro.

The October outlook is looking like a dry one, meaning drought is likely to expand and intensify before it gets better. With three-month precipitation deficits of 3 to 6 inches in the Piedmont and 4 to 8 inches in the Mountains, it will likely take several weeks or months of above-normal rainfall to fully recover.

To help us monitor the emerging drought, you can submit any impacts you observe using the Drought Impact Reporter or through the CoCoRaHS Condition Monitoring program if you’re a CoCoRaHS observer.

While we may not have much rain to track at the moment, we can still tell how the lack of it is affecting conditions across the state.