Perhaps the most famous pictures taken during Hurricane Floyd were not of people but of pigs. Aerial shots showed hog farms flooded by the storm, with the animals who hadn’t drowned riding out the event from the roofs of barns.

It wasn’t exactly pigs flying, but the livestock — like the flood waters that drove them up there — had reached historic heights in the wake of the storm.

With much of eastern North Carolina under water, Floyd was truly devastating, and the agriculture sector bore much of that impact.

An estimated 30,000 farms in the state suffered a quarter-billion dollars in structural damage, a half-billion in crop damage, and $800 million in property losses. It was in excess of a billion-dollar disaster for the industry.

State officials said half of the peanut, cotton, soybean, and sweet potato crops were lost, as well as 40% of the tobacco crop. Nearly 3 million animals died, mostly due to drowning. In Duplin County alone, 750,000 turkeys and 100,000 hogs were killed by the storm.

The flooding on hog farms created another hazard. Lagoons used to store animal waste were breached by the flooding, carrying that toxic sludge into waterways and contaminating drinking water with bacteria and viruses, including E. coli.

But Floyd wasn’t the first case of such an environmental emergency. In 1995, the dike securing an eight-acre lagoon on a farm in Onslow County collapsed, spilling 25 million gallons of wastewater into the New River.

That part of southeastern North Carolina was acutely aware of the threat, and when Floyd arrived, they were the first to feel its impact.

On the Ground in Onslow

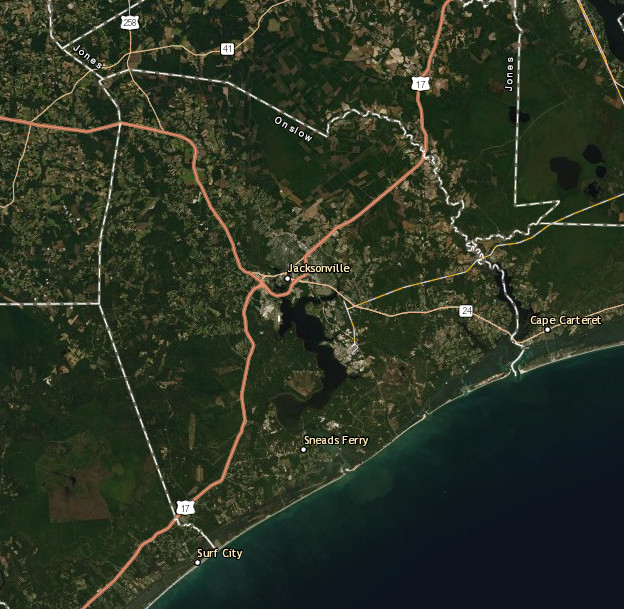

Onslow County is the home of Jacksonville, Camp Lejeune, and the New River, a relatively short 50-mile waterway that winds through the county from northwest to southeast before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean.

The geographical borders of Onslow County also follow the hydrological borders of the New River watershed, which means no surface water from any other county enters Onslow.

Diana Rashash is an area specialized agent in water quality and waste management with the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service. She has been in that role since 1996, and she was in Onslow County during Floyd.

The eye of the storm passed directly over Jacksonville — at night, no less — so the initial concerns were over power and telephone outages, which made it difficult or impossible to communicate with colleagues and farmers across the county.

“With Floyd, a lot of cell phone towers were down and it got harder to communicate from a distance,” said Rashash.

Getting around after the storm was also a challenge, and several roads around Jacksonville did flood. That meant taking to the skies in a helicopter to begin surveying the damage, and for Rashash, it’s not hogs on roofs but a different image from those aerial surveys that stands out in her mind.

“Floyd was really impressive for the New River looking at the sediment plume going out into the ocean,” she said. “It went out miles.”

Unlike in other parts of the coast, where it took days for upstream rains to work their way down the Tar and Neuse rivers, the short New River rose — and fell — within 24 hours after Floyd hit.

“While everyone else was bracing for the water or dealing with the water, these folks were already starting cleanup,” said Rashash.

Hog lagoons were a concern and in some places were covered by several inches of rain water and inundation from the New River.

“It was like a layered salad. Sludge at the bottom, then lagoon water, then river water since they all had different densities,” she said.

Pumps were brought in to get the lagoon levels down, and in Onslow County, no lagoons were breached and no hogs were killed by the storm. It was a fortunate fate compared to other hard-hit parts of the coast.

Rashash said the Cooperative Extension Service, the Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, local Soil & Water officials, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service all pitched in to help farmers affected in her county.

Lessons from the Storm

Because of Onslow County’s location along the coast and the storms preceding Floyd in the late 1990s, it was perhaps better prepared to handle a hurricane than areas farther inland.

“The ’90s in general pointed out the need for generators,” said Rashash. “Because we did have several hurricanes during the years before, we had people that had a lot of trees down and had a lot of power outages. Producers were caught without having generators, which was an issue for livestock.”

But Floyd made farmers focus on more than just the wind forecast and power outage potential.

“Now they do pay more attention to the rain — it’s going to be like Floyd, it’s going to be worse than Floyd, it’s going to be like Florence.”

Rashash said the flooding also made people across eastern North Carolina become more aware of their local flood zone maps. Some farms within the floodplains received buyouts after Floyd, but the supply did not meet the demand.

“A lot more farms are interested in buyouts than get bought out because of the amount of money available,” said Rashash.

And since Floyd hit, it’s not just farms dealing with that problem.

“It’s also the subdivisions that have been put into low-lying areas,” she added.

Although Florence was wetter for Onslow County, in some spots dropping up to 30 inches of precipitation, the lessons learned from Floyd, such as farmers “running their tractors 24 hours per day” to harvest as much crop as they could ahead of the storm, helped them prepare for last year’s flood.

In that sense, “Floyd has become a benchmark,” said Rashash.

Or perhaps stated more appropriately given the height of the flood waters, “people have used it as a yardstick.”

Sources:

- Business Response to Natural Disaster: A Case Study of the Response by Firms in Greenville, NC to Hurricane Floyd by Ann Angelheart, University of Florida (2002)

- Huge Spill of Hog Waste Fuels an Old Debate in North Carolina from the New York Times, June 25, 1995

- Hurricane Floyd, 1999 from East Carolina University’s Storms to Life