This is the second post in our “Stormy Summer” series looking back at some memorable hurricane anniversaries occurring in 2019.

Before the tropical terror that was Hurricane Floyd in September 1999, another storm hit the North Carolina coast, and while its impact at the time was relatively minor, it played a major role in amplifying the flooding and damage when Floyd arrived just 12 days later.

No, Hurricane Dennis didn’t bring the same scenes of destruction as Fran and its other predecessors in the late 1990s, but there’s a reason it became known as “Dennis the Menace”.

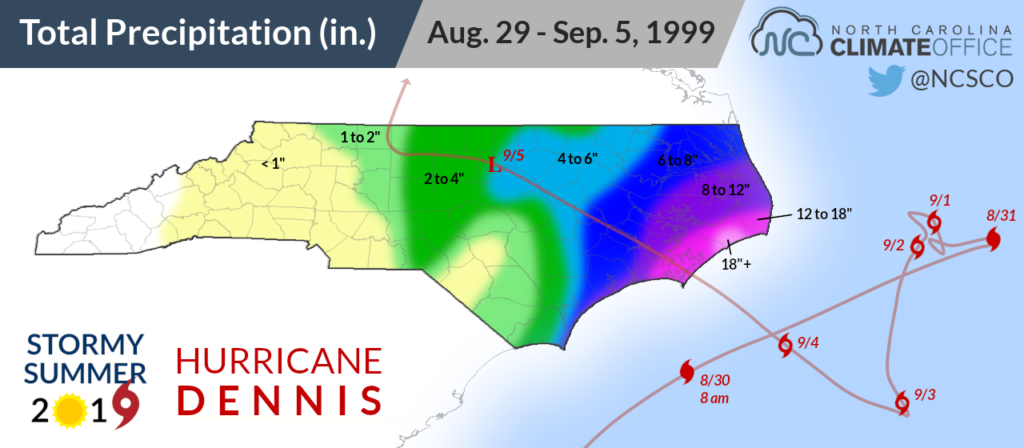

While it spun its wheels off the coast for four days and eventually made landfall, Dennis dropped more than a foot of rain on the Outer Banks and more than six inches over the Tar and Neuse river basins. It was this rain that the soil and rivers were still digesting less than two weeks later when Floyd brought another heaping helping of precipitation.

Because of the role it played in setting up the then-worst flooding event eastern North Carolina had ever seen, Dennis deserves a closer look in this Stormy Summer series.

Dennis was a late bloomer as hurricanes go. Although it first emerged off the coast of Africa as a cluster of thunderstorms on August 17, it didn’t organize into a tropical depression until seven days later when it passed north of Puerto Rico.

Westerly wind shear initially hindered its development, but Dennis became a Category-1 hurricane by August 26 and a Category-2 two days after that as it skirted the Bahamas.

As the National Hurricane Center notes in its report about the storm, Dennis never became particularly well-organized as it approached the North Carolina coast. Instead of a tight, pinhole eye like Fran and Floyd had at their strongest, Dennis had a wide, often ragged eye 30 to 40 miles wide.

However, the eye’s larger diameter also meant strong winds extended farther out into the storm. Despite being up to 80 miles from the center of circulation when Dennis passed by on August 29, points on Cape Fear, Cape Lookout, and Cape Hatteras all experienced hurricane-force wind gusts.

Once Dennis was parallel with Hatteras, it came to a standstill. Blocked by a strong high pressure system building in from the Great Lakes, Dennis’ northeasterly movement slowed to a drift.

A cold front approaching from the northwest brought in cooler air and more wind shear that weakened Dennis back to tropical storm-strength, but it kept spinning its wheels within 200 miles of the coast. As the high pressure system progressed eastward, it eventually pushed Dennis back toward the southwest, although it was still moving at barely a crawl.

For three more days, Dennis danced offshore, churning up the surf and kissing the Outer Banks with its outer rain bands.

High pressure shifting to the east finally brought Dennis’ do-si-do to an end, but the storm then kicked toward the coast and made landfall near Cape Lookout as a tropical storm just before 5 pm on September 4.

The remnants of the storm crossed the state before moving up the Foothills into Virginia. By then, it had dropped 19.13 inches of rain on Ocracoke Island over a seven-day period, and more than half a foot from Jacksonville to Elizabeth City.

In the days that followed Dennis’ landfall, coastal rivers crested and water levels never came back down before Floyd came ashore on September 16. The Tar River in Greenville and the Neuse River in Kinston passed their flood stages of 13 and 14 feet, respectively, before surging even higher from the extra precipitation Floyd brought.

Floyd would have still been a major flood event on its own, but the saturated head start Dennis provided made it even worse. And that eventual flooding wasn’t the only impact in the state from Dennis. For the better part of a week, it was a not-so-distant reminder of the hazards of a hurricane.

The stubborn storm toppled trees and power lines along the coast. At the Outer Banks, high surf and storm surge — first from the ocean side, then from the sound side — eroded sand dunes, cut across Highway 12 on Hatteras Island, and damaged 1,600 homes and businesses in Dare County.

Inland, a combination of wind, rain, and saltwater intrusion affected more than 268,000 acres of crops totaling $14 million in damage. Two deaths from a car accident in northern Onslow County were indirectly attributed to the storm and its rough weather.

Despite the damage and even the deaths, Dennis was generally seen as not as bad as it could have been. The Washington Post noted it “never quite roar[ed] ashore to deliver its full punch” as a Category-2, and the coastal residents interviewed seemed relieved to get off so easily on the storm’s initial approach.

“This is nothing compared to Bertha or Fran or Bonnie,” said Justin Green from Wrightsville Beach. “It was nothing. It wasn’t even constant wind, just gusts. But the beach definitely looks smaller.”

To others, Dennis was a novelty.

“It is pretty fun to be right about to be hit by a hurricane,” said 12-year old Jesse Strickland in Virginia Beach. “Never had that happen before.”

Never before, perhaps, but soon to happen again, as history so unkindly reminds us.

In the 1999 hurricane season, Dennis on its own was mostly a nuisance and would likely be remembered as such — or perhaps barely remembered at all — if not for the storm that followed less than two weeks later.

Indeed, Dennis and Floyd were a turn-of-the-century tandem nearly inseparable in their ultimate impact on the state, but heavily weighted toward the latter in peoples’ minds.

It’s a good reminder that no hurricane occurs in a vacuum. To an extent, each one depends on its predecessors, whether it’s the rain they brought, the landscape they altered, the perceptions they changed, or the preparedness they fostered.

Those factors certainly shape the legacy Dennis left behind. On its own, it wasn’t strong enough, wet enough, or close enough to the coast at its strongest to deal catastrophic damage. Crisis averted, right?

Definitely not. In the stormy summer of 1999, Dennis was only the beginning of a tropical one-two punch that left a devastating mark on the state.