NC State University senior Jack Kendrick spent last summer studying mountain inversions as an ECONet Summer Undergraduate Student Intern.

When Jack Kendrick’s alarm went off around 5:30 a.m., he felt one thing — excited. It was June and about two weeks into the then-rising senior’s internship with the North Carolina State Climate Office (SCO). Such an early start to the day was unusual for Kendrick’s internship, but he had an unusual day ahead of him.

By 7 a.m., Kendrick met ECONet instrumentation technician Myleigh Neill outside the Climate Office on North Carolina State University’s Centennial Campus. After loading a truck with gear, the pair set off toward their destination: Mount Mitchell in Burnsville, North Carolina.

Four and a half hours later, Kendrick stepped out of the truck, now more than 6,000 feet above sea level. Surrounding him was a view of the mountains, but in front of him stood a 33-foot aluminum tower. This wasn’t Kendrick’s first time seeing an ECONet tower, but it was the first time he would get to work on one.

An ideal day at work

landscape. Photo by Jack Kendrick.

ECONet is North Carolina’s Environment and Climate Observing Network that spans 35 counties in North Carolina and one county in South Carolina.

More than 45 ECONet towers across the state collect local atmospheric and soil measurements, which are relayed to SCO every five minutes. That can include data such as air and soil temperature, wind chill, and precipitation amounts. In some locations, there are 15 years’ worth of these five-minute measurements, creating a detailed database of weather and climate observations that state and federal agencies use for a variety of applications.

For decades, SCO has hosted an ECONet Undergraduate Student Intern nearly every summer. The paid position runs from approximately the end of May through mid-August, with students expected to work about 29 hours per week.

Up to two days a week may include fieldwork at ECONet stations; at Mount Mitchell, Kendrick tested the calibration of the foot-tall rain gauges. Then, he did some digging for the HMP sensor that measures the area’s temperature and relative humidity:

“All of our sensors have some kind of lifetime, essentially.” Kendrick said. “So, after a certain amount of time, it’s just time to replace it. Temperature and moisture stuff is underground. You have to find a wire running from the station and then carefully dig it up and replace it.”

Kendrick’s 12-hour trip to and from Mount Mitchell was one of his longest workdays, but one that he found most exciting.

“That one’s a treat just because you get to go to the mountains,” Kendrick said. “That day in particular, I was like, ‘I picked the right internship.’ I just got to go to the mountains for a day trip and work on a weather station and come back. That was pretty much an ideal day at work for me.”

Kendrick visited about 25 ECONet stations by the end of the summer, but his work with the towers continued beyond the field.

ECONet applications

The overarching goal for each ECONet intern is to complete an independent research project utilizing the towers’ data, with the guidance of ECONet manager Sean Heuser.

Being born in Boone and having a strong desire to move back to the region someday, Kendrick said that he knew he wanted to take on a project with a mountains-based focus:

“It’s just — I think it’s the most beautiful place in the world,” Kendrick said.

The region isn’t without its challenges, though, particularly when it comes to accurate weather forecasts. With areas like Asheville being in the same TV market as Spartanburg and Greenville, South Carolina, Kendrick said that coverage tends to cater more to South Carolina.

“And then,” Kendrick added, “there’s just such high variability in the mountains with the weather that you need a little more research into how things work up there to be able to get accurate forecasts. It’s always kind of a muddy picture in the mountains. You have lots of forecast inputs, and lots of people saying different things.”

Per Heuser’s suggestion, Kendrick settled on a project focused on synoptically-driven temperature inversions in the mountains — instances of cold air trapped beneath warm air, caused by large-scale weather systems.

“Usually the temperature decreases as you go up,” Kendrick said. “When you have an inversion, the opposite occurs. Once the sun goes down, the cold air is more dense, and that causes it to kind of sink and gather at the ground level. In the mountains in particular, it’s exaggerated by the fact that you have steep topography that can pool that colder air really down in the valleys.”

Kendrick’s goal was to create a baseline understanding of when the mountain inversions occur and how strong they are using data tracked by ECONet stations for the past decade.

He used four pairings of stations for his work, each consisting of one high-elevation tower and a nearby low-elevation tower. For example, Mount Mitchell’s ECONet station at 6,000 feet above sea level was paired with the ECONet station in Burnsville, located in a valley with an approximately 2,000-foot elevation.

Kendrick could compare the temperatures recorded by the higher station to those recorded by the lower station to see if any inversions had occurred, which for his project was defined as a temperature difference of at least 0.7 degrees Fahrenheit for at least an hour. He looked at every temperature that each station had recorded every 15 minutes, every day for 10-15 years.

“I would end up with 20 spreadsheets for each station,” Kendrick said.

But all that number-crunching yielded results: Kendrick found inversions were generally strongest during times of drier and clearer weather, which would be late fall and early winter in North Carolina. One of the most drastic inversions Kendrick found was recorded between the Frying Pan Tower’s station at 5,300 feet in elevation and the Waynesville’s station in the valley at a 2,000-foot elevation. The higher station had recorded a temperature that was about 35 degrees warmer than the temperature at the Waynesville station.

“Imagine you’re sitting at 22 degrees in the morning in Waynesville and you drive up to the parkway and it’s 56 degrees.” Kendrick said. “It’s a very different situation.”

Beyond impacting choices of outerwear, inversions can affect air quality. When cold air gets trapped beneath warm air, pollutants get trapped with it, sometimes leading to instances of reduced visibility.

“Salt Lake City is a great example of really bad inversion,” Kendrick said. “You can physically see if you get above it a layer of gray haze that’s stuck over the city. You can see this too in our mountains, but not to the same degree. When you have an inversion, your air quality is going to be a little worse.”

Now that Kendrick has established a thorough record of mountain inversions, he said that he’d be interested in delving into their practical effects for future research to figure out what such weather events actually mean for the people who live in the region.

“I could put together a more accurate depiction of how much it affects the air quality,” Kendrick said. “Is there a time when you need to limit outdoor activity because of air quality effects? How often does it affect visibility?”

Career prep outdoors

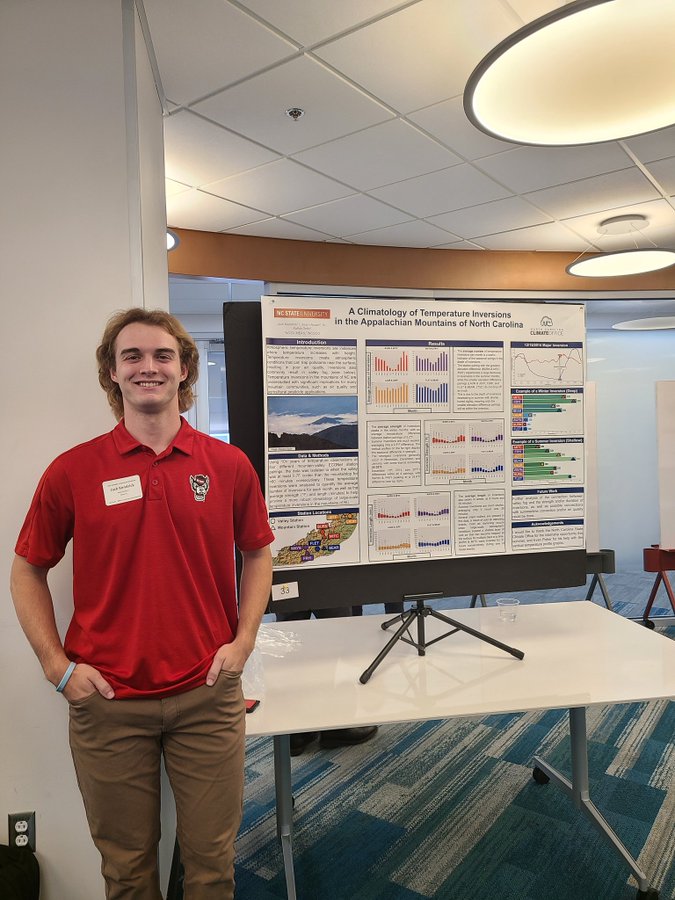

State Summer Undergraduate Research and

Creativity Symposium. View on Instagram.

Kendrick’s internship culminated at the end of July with a poster presentation of his research at the NC State Summer Undergraduate Research and Creativity Symposium in D.H. Hill Library. Though it was Kendrick’s first time presenting in a conference-style environment, he wasn’t too nervous — he enjoyed getting to share what he’d spent months working on and seeing others so interested in that work.

Now a senior hurtling toward graduation, Kendrick said that his ECONet internship helped him understand what he would like out of a job, and he had clear advice for prospective applicants:

“You absolutely should apply for it, especially if you enjoy the outdoors,” Kendrick said. “I don’t know of another meteorology job that you could have for summer in college that is going to get you outside as much as this one’s going to. Just be patient with learning, and if you’re not sure about something, ask questions about it.”

Applications for the 2025 ECONet Summer Undergraduate Student Internship close February 24.