For the second time in just six weeks, parts of southeastern North Carolina have seen more than a foot of rainfall from a slow-moving storm system.

The latest event exceeded the totals and the local flooding impacts from Tropical Storm Debby back in August, and perhaps most impressively, this was not even a categorized tropical storm or hurricane.

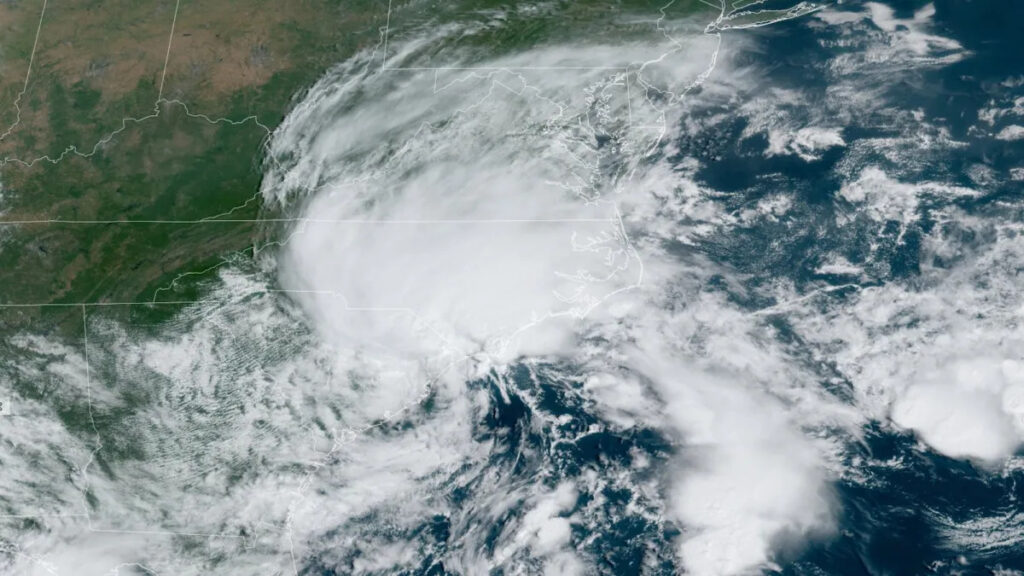

The offshore system first developed last Saturday along a stalled frontal boundary. While the National Hurricane Center briefly investigated it as Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight, they never found a well-defined center of circulation – a key part of a tropical storm’s structure – and they noted any low-level circulation was elongated from northeast to southwest, a remnant of its frontal origins.

Although it was classified as a run-of-the-mill low pressure system, its impacts in North Carolina were anything but ordinary. Sitting over ample reserves of Atlantic moisture and drifting at a scant 3 miles per hour by Monday morning, it effectively pointed a firehose at our state for four days straight.

If those details sound familiar, it’s because there were plenty of similarities to Debby, from the same crawling forward speed to the same duration – delayed again due to the roadblock of high pressure to the north and west – to a nearly identical track moving northwestward across the Carolinas. That meant many of the same areas were affected as during and after Debby.

Heavy Rain and Flooding

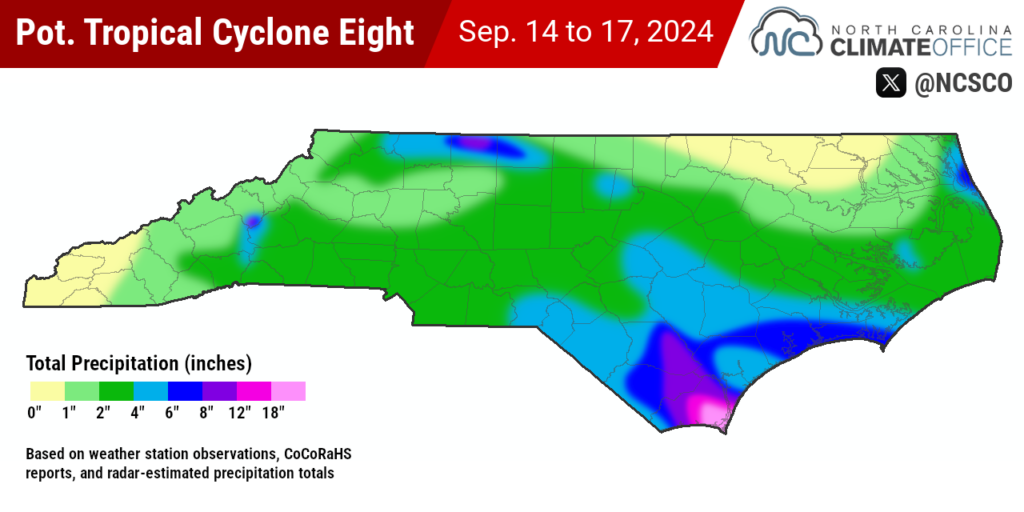

Storm-total rainfall amounts of at least 2 inches were recorded as far west as Haywood County, with widespread coverage of those higher amounts across central and eastern North Carolina. Parts of the northwest Piedmont received heavier rain from a band of thunderstorms on Tuesday night, including 6.87 inches at our ECONet station in Reidsville.

The highest totals exceeding eight inches occurred across the southern Coastal Plain, with more than 12 inches in New Hanover and Brunswick counties. In their recap of the storm, the National Weather Service in Wilmington noted a storm total of 20.81 inches on Ocean Boulevard in Carolina Beach, and several CoCoRaHS observers in southern Brunswick County measured more than 15 inches, including a 20.19-inch maximum near Southport.

Our office’s ECONet station on Bald Head Island reported 20.26 inches from Saturday through Monday, including 12.29 inches on Monday alone, which is the wettest single day our stations on the island have measured since 2015. Along with the rain, Bald Head Island also had a short-lived tornado on Sunday morning after a waterspout moved onshore.

The Remote Automated Weather Station (RAWS) at the Sunny Point Military Terminal had 18.79 inches in total, with a maximum hourly amount of 4.61 inches reported at 11:18 am on Monday.

After that rainfall, the Lumber, Neuse, and lower Cape Fear River were each rising toward their flood stages, with the Northeast Cape Fear River near Burgaw expected to crest at or near its moderate flood stage.

For coastal communities, the impacts were much more immediate. Numerous roads in Brunswick County were under water or washed out. State and US highways in Columbus Counties were also closed due to flooding. Carolina Beach was inundated to a depth of at least three feet, and local elementary school students were evacuated in high-water vehicles amid the fast-rising flooding on Monday.

That spoke to the deceiving nature of this system: seemingly so disorganized that it wasn’t a named tropical storm, but armed with enough moisture that it turned a wet day into an emergency amid hours of unrelenting rainfall. Similar to Ophelia one year ago, which also began as a Potential Tropical Cyclone along a stalled frontal boundary, it snuck in under the radar and punched above its weight.

Another Extreme Event

For an event that began six years to the day after Hurricane Florence made landfall, PTC8 was another reminder that Florence is far from the only flooding storm in our state’s recent history.

It joins Tropical Storm Idalia’s inundation of Whiteville and the swollen rivers and overtopped roadways after Debby among impactful flood events just in the past 13 months.

This latest storm adds to the evidence that these extreme rain events are much more common now than ever before. That shows in the data itself. Rainfall return frequencies from the older Atlas-14 dataset consider the 20.26 inches over three days on Bald Head Island as a nearly 1-in-500 year event.

Southport had a similar 1-in-500-level event during Hurricane Floyd in 1999, with 18.30 inches in just 24 hours. And southern New Hanover County had 31.26 inches in four days during Florence: far beyond the 1-in-1000 year total of 24.2 inches from the historical Atlas-14 dataset.

Along with demonstrating the need for updated and more accurate rainfall return frequency data – and our office is currently working on just such a project to give our partners such as the NC Department of Transportation better perspective about these extreme events – this flurry of recent flooding storms continues to highlight the potent impacts of climate change in North Carolina.

A warmer and wetter atmosphere means storm events – including hurricanes – are becoming supercharged with moisture, and our rarest, wettest days are becoming much more common. Recent trends also show storms are moving more slowly near land and blocking high pressure patterns are becoming more common, which adds to the rainfall potential when those systems line up.

For parts of our southern coastline, that potential was realized again this week, as 20 inches of rainfall left familiar flooding scenes behind and helped this unnamed storm make a name for itself as one of the locally wettest events on record.