For the past 8 months, our office has been involved in writing the North Carolina Climate Science Report, the first report of its kind for the state of North Carolina. This report was produced at the request of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality as part of the state’s response to Governor Cooper’s Executive Order 80.

The report drew from subject matter experts across the state, and is an independent assessment of peer-reviewed science as it pertains to North Carolina. It was led by our colleagues in Asheville at the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies. Our Director, Dr. Kathie Dello, served as a report author and on the Climate Science Advisory Panel. SCO staff, Ashley Hiatt, and former undergraduate student (now ECU graduate student), Kelley DePolt, were technical contributors.

Here, we post the plain language summary that we helped develop with other report contributors. It will tell you a little bit about the key findings of the full report. If you’re looking for more, check out the full report at ncics.org/nccsr.

Climate change is already being felt in North Carolina, and it will continue to pose a significant challenge for the foreseeable future for the 10.5 million people who call this state home. The continuing release of heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere as a result of human activity makes for a warmer, wetter, and more humid North Carolina. Scientists from across the state agree that the changes to our climate in this century will be larger than anything experienced in North Carolina’s historical past. Climate change will impact our state’s economy, environment, and people. Over the next 80 years, the state can expect disruptive sea level rise, increasingly hot nights, and more days with dangerous heat and extreme rainfall unless the global increase in heat-trapping gases is stopped.

The North Carolina Climate Science Report (NCCSR), led by the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, draws from climate science expertise across the state, as well as from peer-reviewed science, to reach these conclusions. This independently produced report is the first of its kind. It has been thoroughly reviewed by subject matter experts.

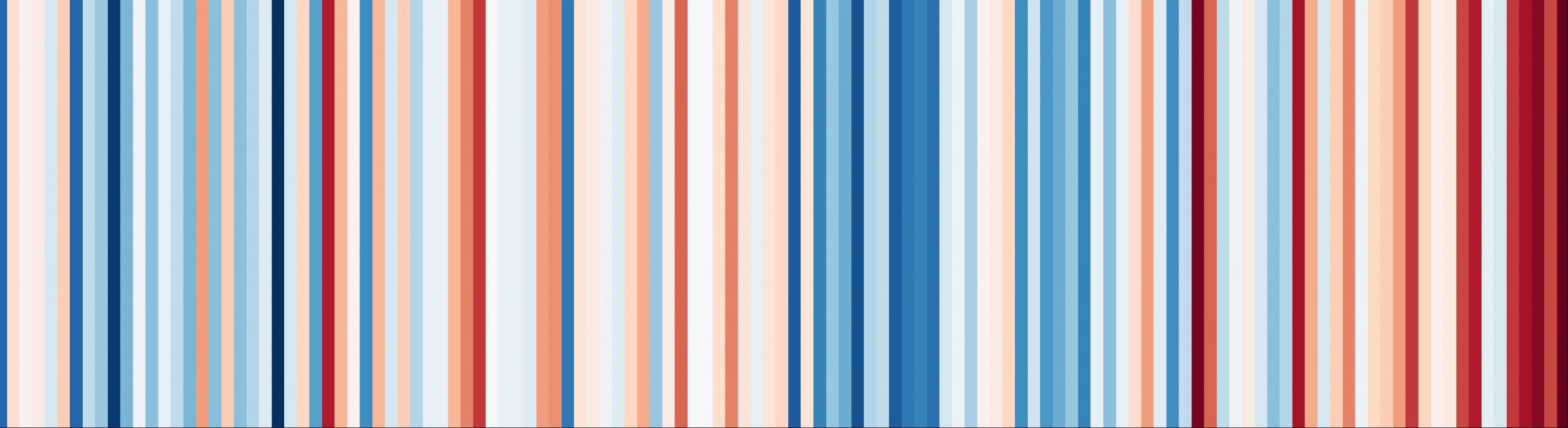

North Carolina has warmed by about one degree Fahrenheit over the past 120 years. This is less than Earth as a whole, which has warmed by nearly two degrees. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), housed in Asheville, NC, maintains meticulous climate records for the country and planet–measured throughout what we call recorded history–by thermometers and rain gauges at official sites by trained observers. From these data, we know that even though the state has warmed less than the planet, warming here has accelerated in recent decades. The last decade (2009-2018) beat out the warm 1930s as the warmest decade on record for North Carolina. While this report was being finalized, 2019 was declared North Carolina’s warmest year in 125 years of record keeping.

Scientists expect the warming to continue in North Carolina through this century, in all seasons. The amount of warming will depend on future emissions of heat-trapping gases. Scientists study future warming using climate models and potential scenarios of how we may continue to use resources and burn fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). If emissions continue to grow rapidly through the end of the century, North Carolina is projected to warm an additional six to ten degrees by 2100. Under a scenario in which emissions increase at a slower rate, peak around the middle of the century, and then begin to decrease, the warming will range from two to six degrees. Emissions are similar in the two scenarios through mid-century, and they suggest a fairly similar amount of warming through about 2050, with the range being slightly greater under the higher emissions scenario.

Nights have been getting hotter, but there is no historical trend in hot days. The last five years (2015-2019) have had the warmest overnight low temperatures on record in North Carolina, with 2019 setting the record for the warmest lows in the recorded past. These warm nights affect public health and agriculture.

In the future, both days and nights are likely to get hotter. This increased heat, together with increases in humidity, will present a public health risk. The heat index is a measure that combines air temperature and relative humidity to get at how the human body experiences these conditions. It is very likely that there will be more days with dangerously high heat index values due to increases in temperature and humidity. In a warmer North Carolina, warmer nights are very likely, and the number of cold days are likely to decrease. Cities tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas because paved surfaces absorb and retain heat. This is called the urban heat island effect, and it is projected to increase as North Carolina warms and our urban areas grow.

There is no trend in annual precipitation, but extreme rainfall has increased in the recent past, including a new statewide record for precipitation. 2018 was North Carolina’s wettest year on record in 125 years of record keeping, partially as a result of Hurricane Florence, which produced the heaviest rainfall in North Carolina history. The 2015-2018 period saw an increase in the number of days with very heavy rain, defined as 3 inches or more in 24 hours. The official climate station on Mt. Mitchell received 139.94 inches of precipitation in 2018, which set a new statewide precipitation record.

Heavy rains from hurricanes and other weather systems will become more frequent and more intense. Annual precipitation is also expected to increase. These changes are driven primarily by increases in atmospheric water vapor as the climate warms. Extreme rainfall in North Carolina can result from hurricanes (as experienced in recent years with Dorian, Florence, Matthew, and Michael), from Nor’easters (strong coastal storms with winds from the northeast), or from other weather systems like thunderstorms. Severe thunderstorms are also likely to increase in a warming climate and can cause flash flooding, especially in urban areas.

Increased flooding, due largely to sea level rise, will disrupt coastal and low-lying communities. By the end of the century, these areas will experience high tide flooding nearly every day and a substantial increase in the chance of flooding from coastal storms. The ocean is rising because melting glaciers add more water to the ocean and because sea water increases in volume when it warms. Sea levels are rising faster on the northern coast of North Carolina than on the southern coast, but by the end of the century all of the state’s coast will experience disruptive coastal flooding. Under the higher emissions scenarios, flooding events that are currently rare will become much more likely.

Hurricanes will be wetter and are likely to be more intense, though it is unknown whether the number of hurricanes making landfall in North Carolina will change. Atmospheric water vapor is the fuel for hurricanes. Increased water vapor in a warmer climate will favor hurricanes that are more intense and that will produce more extreme rainfall.

Severe droughts will become more intense, and this will increase the risk of wildfires. Rising temperatures and the resulting increase in evaporation will accelerate the rate at which soils dry out. Thus, naturally occurring droughts in North Carolina will be more severe. The state’s worst ever drought in 2007 led to water restrictions in municipalities; some had less than a 100-day supply of water available for residents. Large agricultural losses were experienced by producers. In 2016, western North Carolina experienced drought and wildfires. It is expected that severe drought impacts will become more frequent in a warmer North Carolina.

To read the full report, please visit ncics.org/nccsr.

div.featured-image{ display: none }