This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

Extreme weather conditions such as drought and high winds can provide an ideal environment for wildfires to ignite and spread. Many of these large fires have occurred on the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula in eastern North Carolina.

That’s no coincidence according to Cabe Speary, Fire Environment Forester with the NC Forest Service. From top to bottom, several factors make this area a hotspot for wildfires.

First, it’s heavily forested with few breaks between the trees. That means fires can easily spread across large areas, especially if high winds are present. The lack of many major roads also makes these areas fairly inaccessible.

Beneath these trees is an understory of shrubs and grasses that provide more fuel for fires. Forestry companies that once cut Atlantic white cedar in this region left behind dead bits of these trees, which historically served as additional fuel. Waxy fallen leaves are also highly flammable, even if the humidity is high.

Beneath the understory, the pocosin soils in this region contain lots of organic matter, which can burn like charcoal several feet underground. The terrain — the term “pocosin” comes from an Algonquin word meaning “swamp on a hill” — is subtle, but 12 to 14 foot rises in elevation mean some spots are higher and drier with deeper layers of organic soil, providing another ready source of fuel for fires.

For groups like the NC Forest Service that respond to hundreds of fires each year, several of these large pocosin fires stand out as being particularly memorable.

1955 Lake Phelps Fire

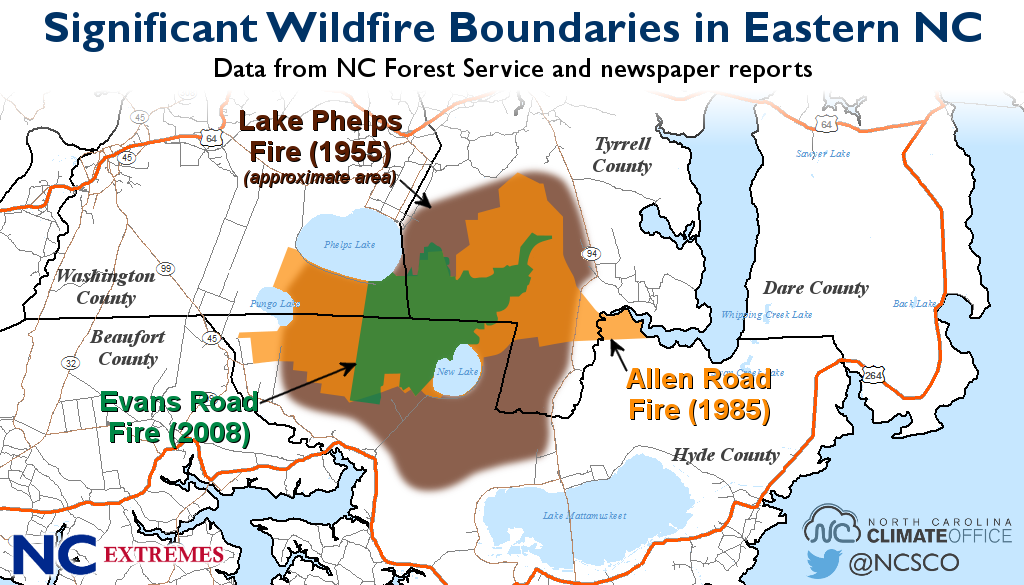

North Carolina’s largest wildfire in recent history occurred in the spring of 1955 near Lake Phelps in Tyrrell, Hyde, and Washington counties. The fire began on the night of March 29 in an apparent act of arson, although the culprit and the evidence were never identified.

Just up the coast in Norfolk, sustained winds were measured at up to 23 mph. Similar winds helped the fire spread quickly and unpredictably. Efforts to contain it were hampered by dense smoke, a lack of roads to access the blaze, and soft ground nearby that was tough for heavy equipment to navigate.

Containment efforts involved the state forestry division, the Coast Guard, Army, and Marine Corps, as well as Mother Nature in the form of nearly a half-inch of rain on April 6 and 7. It took eight to ten days of fighting the fire to bring it under control. An estimated 203,000 acres were burned and monetary losses, primarily to privately owned timberland, amounted to three to four million dollars.

The same area suffered another large fire in 1985. That April, the Allen Road Fire was set off by machinery mining the peat soil, according to Speary. That fire burned nearly 95,000 acres, with timber losses estimated at up to $30 million. The fire also consumed more than three feet of peat in some spots.

2008 Fire Season and Evans Road

One of the most active fire seasons in recent memory happened in 2008. We began that year in one of the worst droughts on record, so vegetation and soils were extremely dry and the environment was primed for fire. The powder keg first ignited on February 10, when a cold frontal passage brought in dry air and high winds, and more than 300 fires started across the state.

More fires popped up in March before rainfall and the greenup of vegetation appeared to reduce the fire risk. However, the summer brought a new threat: lightning. One strike in particular occurred on June 1 just south of Lake Phelps, setting off the Evans Road wildfire.

Speary said the origins of that fire made it particularly difficult to respond to. The lightning strike occurred on private property in a remote area on a weekend. No aircraft were available immediately, and by the time they were, the fire was already getting big.

On June 1 alone, nearly 700 acres burned. By June 4, it had burned almost 12,000 acres, and by June 14, it grew to more than 40,000 acres before its growth was largely stopped. The pocosin landscape made containing this fire particularly difficult.

“When it gets that big and that bad, your only option is to flood it,” said Speary. Flooding it meant pumping water from canals and lakes and sometimes transporting it several miles to the fire. Even this response could only raise the water level so much, so additional rains were also needed. “You just have to wait for nature to take its course,” he said.

The Evans Road fire continued to burn and smolder underground for several more months. At times, it even burned beneath roads and canals. It took more than two billion gallons of water and nearly seven months — until January 2009 — before the final hotspots were extinguished.

As the fire continued to smolder, the smoke it emitted presented another hazard. In the northeastern Coastal Plain, particle pollution levels were measured at more than 50 times the 24-hour standard, leading to Code Purple — very unhealthy — air quality conditions. Even locations as far inland as Winston-Salem saw and smelled smoke on June 12 and 13 when easterly winds pushed smoke across the state.

The Evans Road fire burned nearly 42,000 acres, most of which were in the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. That helped make 2008 one of North Carolina’s worst years for wildfires since 1985.

Managing for Future Fires

Fortunately, Speary says large fires like those at Lake Phelps, Allen Road, and Evans Road are becoming rarer for several reasons. Technology such as cell phones means fires are generally reported sooner, leading to a quicker response, especially by local volunteer fire departments. Better equipment such as helicopters and air tankers have also increased the capabilities of the Forest Service.

Improved management practices have also helped. Timber cutting now leaves less debris behind to fuel fires. Prescribed burning is being done more frequently, including on the Pocosin Lakes Refuge. And human developments such as roads, agricultural fields, and new water control structures like canals have created artificial breaks between the trees.

The downside to development is that more homes are now in closer vicinity to historically fire-prone areas and could be threatened by large fires. However, Speary said having another fire the size of the 1955 fire at Lake Phelps is “possible, but not nearly as likely”.

“It would take something special.”

Sources:

- America’s Wetland: An Environmental and Cultural History of Tidewater Virginia and North Carolina by Roy T. Sawyer (2010)

- Evans Road Fire on Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Officially Declared ‘Out’ from the Coastal Wildlife Refuge Society