Strong El Niño Drives Pacific Patterns, Jet Stream Impacts

The second post in our 2015-16 Winter Outlook series turns to the Pacific Ocean for an update on El Niño and its possible impacts to North Carolina this winter.

Over the past nine months, the waters of the equatorial Pacific Ocean have been warming and one of the strongest El Niño events on record has emerged. El Niño’s impacts on North Carolina are greatest in the winter, so what might we expect this year, and exactly how does El Niño affect our winter conditions?

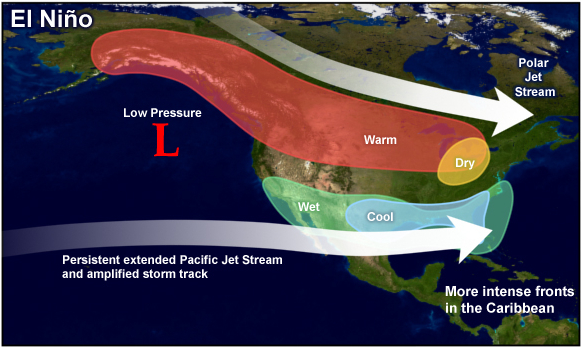

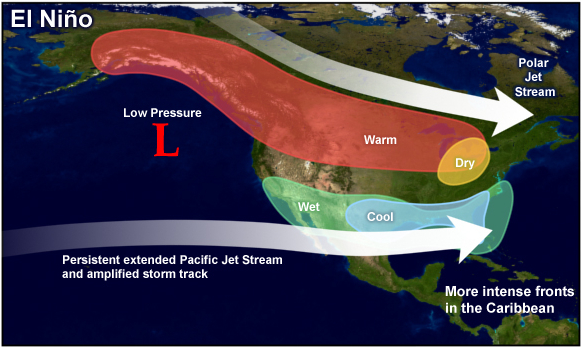

El Niño is just one part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) — a pattern that oscillates or changes from a cool phase (La Niña) to a warm phase (El Niño) over a period of several years. As the water in the Pacific warmed this year and we entered an El Niño phase, the air near the ocean surface also warmed and rose, forming clouds and thunderstorms.

That warm air plus weaker easterly trade winds induced by the Pacific thunderstorm activity help enhance the southern branch of the westerly jet stream, which gets its strength because of north-to-south temperature differences.

The strong jet stream to our south should help developing storms track across the Gulf of Mexico and off the North Carolina coast.

For that reason, we’re fairly confident in seeing a wet winter for North Carolina, particularly east of the Appalachians, which often mark the boundary between wet and dry El Niño impacts.

Temperature impacts are trickier to nail down. Although some El Niño years are cooler than normal in North Carolina, that’s not always the case, and it often has more to do with polar patterns than the El Niño-affected southern jet stream.

El Niño Characteristics

For this winter, several intricacies with the current El Niño event may shape the sort of impacts we see. In particular, the strength, position, and timing of the current El Niño are worth noting.

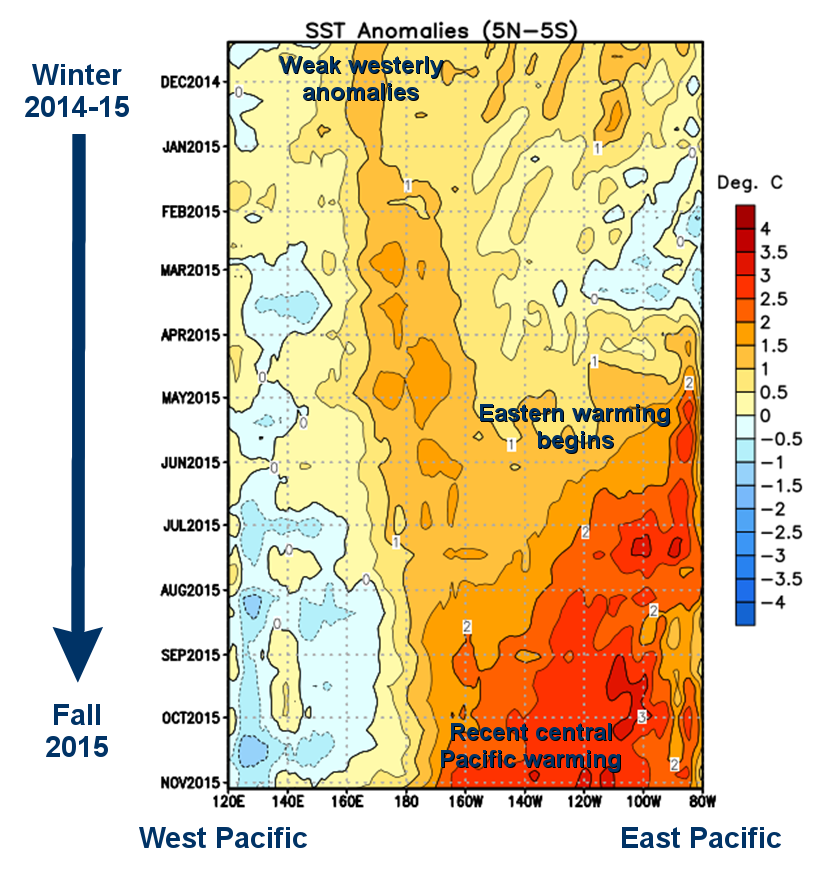

Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are currently 2 to 3°C above normal, and they are likely to warm even more over the next few months. That should make this one of the top two strongest El Niño events since 1950, joining the 1997-98 event near the top of the list.

Stronger El Niño events are generally associated with greater impacts to North Carolina in terms of liquid — but not necessarily frozen — precipitation. In 1997-98, North Carolina had its wettest winter on record. However, that winter also saw below-normal snowfall thanks to unfavorable patterns in other parts of the atmosphere, which we will discuss in our next Winter Outlook post.

El Niño is defined by warm water in the equatorial Pacific, but the location of the warm anomalies can vary from one event to another. During the 1997-98 event, for instance, the greatest SST anomalies were located over the eastern Pacific near the South American coast, making that an east-based El Niño.

On the other hand, the 2009-10 event was a bit weaker but the warm anomalies were located more toward the central Pacific, making that a west-based or “Modoki” El Niño. Some research suggests that these events can be more favorable for cold and snowy winters across the Southeast US, which was the case in 2009-10.

This year’s El Niño pattern falls somewhere in between, as the map of SST anomalies above shows. Warm anomalies begin at the South American coast but a warm tongue also stretches far to the west, so it’s more of a central or basin-wide El Niño. That may mean its position neither helps nor hurts our chances of wintry weather.

As we covered in a previous blog post, El Niño events generally emerge by the late spring or early summer. However, this year’s event took shape a bit differently. For most of last winter, SST anomalies hovered around 0.5°C above normal — the El Niño threshold — but began to increase late last winter and early in the spring, particularly in the eastern and central Pacific.

So will the early emergence of this year’s El Niño also mean an early departure this winter? Current model projections suggest a peak sometime in November or December — perhaps a month or two earlier than in a typical El Niño year — with SST anomalies decreasing after that.

In past years where the peak came much earlier than normal, the impacts also shifted earlier in the winter. In 1987-88, SSTs peaked in the early fall, and during the following winter, our frozen precipitation all came by mid-January while February and March were particularly dry.

Since this year’s peak SSTs won’t come that early and should remain quite strong even late in the winter, we probably won’t see such a drastic shift in impacts, but we could potentially see a wet and favorable wintry pattern fade by the late winter.

Other Pacific Patterns: The PDO and PNA

El Niño isn’t the only pattern we’re watching in and over the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), like ENSO, consists of a warm and cool phase that alter upper-level atmospheric winds. The PDO is currently in the warm phase as it has been since last winter, with above-normal water temperatures off the west coast of North America from Alaska to the equator.

Researchers have found that when ENSO and the PDO are both in the warm phase, El Niño impacts may be enhanced. In addition, a warm PDO phase significantly favors a positive-phase Pacific/North American (PNA) pattern, which describes how weather patterns set up across the north Pacific and North America.

Last winter, as a result of the warm-phase PDO, the PNA was in the positive phase for most of December, January and February, which favored ridging and warm weather over the western US and troughing with cooler conditions over the east coast.

That pattern was one of the dominant forces behind each of our late-winter precipitation events. More impressively, these events occurred in the absence of a negative North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) pattern, which is generally a necessary ingredient for our big snowfalls.

Our confidence is high that the PDO and the PNA will remain in similar configuration — a positive phase — as we’ve observed since last year. Along with the active subtropical jet stream and southerly storm track courtesy of El Niño, we expect to have favorable upper-level patterns for wet and wintry weather across the Southeast US for at least part of this winter.

Conditions in the polar jet stream could also impact our chances of seeing wintry weather this year. Stay tuned on Tuesday for our next blog post in this series, which will cover the potential phases of polar patterns for the coming winter.

- Categories: