Rapid Reaction: Drought Comes Back, in a Flash

A little over six weeks ago, the town of Bayboro, which sits on the Pamlico River along North Carolina’s central coastline, was soaked by 1.89 inches of rain in a single day on July 7.

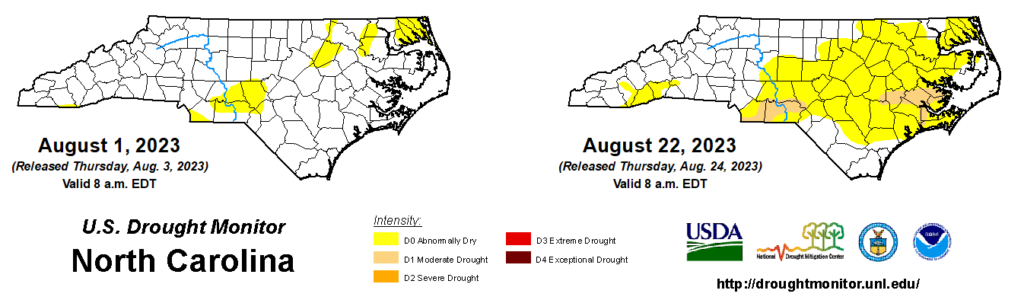

Since then, they have had just 1.87 inches in total, putting them more than six inches below normal during that time period. As a result of that lack of rainfall compounded by the heat, parts of the central Coastal Plain including Pamlico County were classified in Moderate Drought (D1) on last week’s US Drought Monitor.

This week, drought expanded in that region with Kinston now in D1, and it also emerged across parts of the southern Piedmont that have been mired in a similarly dry stretch. One CoCoRaHS observer in northern Richmond County has measured just 1.60 inches of rain over the past two months.

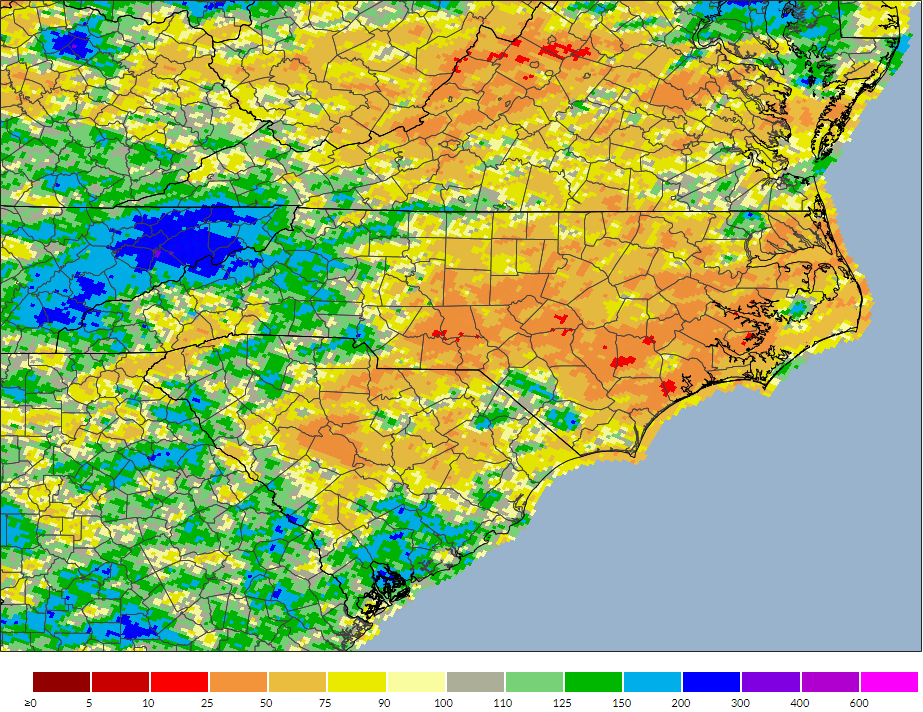

While for now drought covers just 5% of the state, it’s undoubtedly getting dry in many other areas. An additional 47% of the state is classified as Abnormally Dry (D0), including much of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain where less than 50% of the normal rainfall has fallen over the past 30 days.

This is the first time we’ve had drought in North Carolina since April 25, and it may seem like an abrupt addition following our cool start to summer in June and the scattered – and at times, severe – thunderstorms across the state in July.

But after several weeks of hot and dry weather especially for the eastern half of the state, any of that excess moisture from earlier in the summer has long since evaporated, leaving us on drought’s doorstep in August.

Facing a Flash Drought

These rapidly emerging drought events are often called flash droughts, and they tend to take root with exactly these sorts of weather conditions: sustained heat and scarce rainfall, often under the heavy hand of high pressure across our region, which we’ve seen frequently since the beginning of July.

In recent weeks, cold fronts moving in from the west have had their moisture squeezed out over the mountain slopes, with little to no rain reaching the rest of the state.

Between July 17 and August 3, Kinston had only one day with measurable rainfall, and that totaled a measly 0.03 inches, along with temperatures as high as 96°F. As of Monday, the past month there ranked as the 2nd-driest in the last 57 years, with just 1.46 inches of rain compared to an average of 6.11 inches.

Although exact definitions vary, flash droughts are sometimes classified as having at least a two-category degradation on the US Drought Monitor within a four-week period. Indeed, on August 1, the central Coastal Plain was clear of any drought or dryness, but they saw degradation during consecutive weeks since then.

A blended product by the National Drought Mitigation Center that combines multiple short-term datasets – including precipitation-based drought indices and soil moisture data – also pinpoints that area as seeing flash drought emergence.

Current Impacts

While much of the state is likely to have seen some signs of dryness – such as lawns turning brown and small streams running low – during our recent stretch of brutal summer heat, the driest areas are seeing even more pronounced impacts.

From the Sandhills through the northern Coastal Plain, some streamflows have fallen below the historical 10th percentile for this time of year. And that doesn’t just apply to the smallest streams; it even includes the Lumber River near Maxton, which is at its 9th percentile over the past week.

After several weeks without significant rainfall, soils have dried out from the top down. Over a layer 2 meters (or about 6 feet) deep, parts of eastern North Carolina are seeing soil moisture levels running below the 2nd percentile.

Across the agriculturally active eastern part of the state, farmers are feeling the effects of the dryness and drought as well. Last week, Pitt County Extension reported that cotton, peanuts, and soybeans were all wilting, and in Robeson County, crops especially in sandy soils were showing stress.

While corn is typically close to being harvested at this time of year, its progress has slowed amid the dry weather. Since mid-July, the percentage of corn denting – or developing dimples on the kernels as their moisture content decreases and their starch content increases – has been lagging behind the five-year average, per the USDA/NASS Crop Progress reports.

Summer isn’t often an active time of year for wildfires since green vegetation and high humidity levels tend to keep things from burning as easily, but amid our emerging drought, fire activity has increased. On August 19, a wildfire started in a marshy area near Spring Creek in Pamlico County, and it has since burned 264 acres and was 90% contained as of Tuesday.

One impact we’re thankfully yet to see is the implementation of water use restrictions or conservation advisories. That’s in part because of the short-term nature of the current dry spell, and also because upstream rainfall has been generally plentiful, especially for reservoirs in the western Piedmont and Foothills.

However, some coastal water systems in particular – which don’t have the benefit of storage reservoirs, and instead rely on shallow underground aquifers – could face those concerns without rain soon.

Awaiting a Wetter Pattern

In the short term, there isn’t much relief in sight with high temperatures expected to approach 100 degrees on Friday. The heat should back off and rain chances should slightly ramp up by Sunday as a cold front moves in from the north. Precipitation totals through Monday could exceed an inch in some eastern areas, which would eat into — but not totally eliminate — the widespread precipitation deficits of more than 3 inches over the past month.

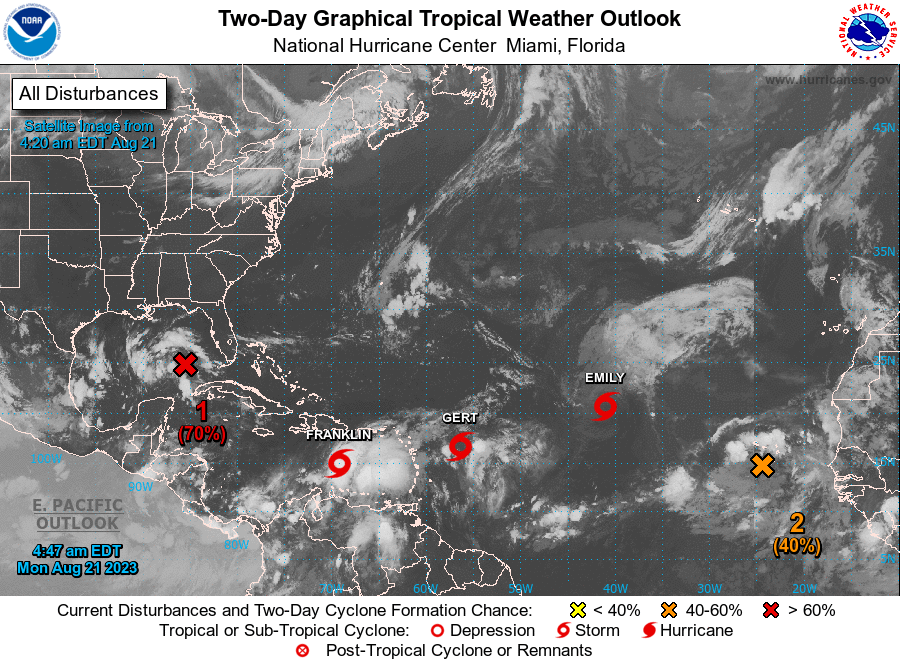

A common truth about drought in North Carolina is that the best remedy is often a timely tropical storm. That was the case with Ian and Nicole last year, Dorian in 2019, and countless other events.

While the Atlantic was quiet to start the month, it has shown signs of awakening this week with four named storms forming, and NOAA’s updated seasonal outlook calls for above-normal activity due to the prevailing warm water across the basin.

Although none of the current storms is expected to impact North Carolina, a busier basin approaching the peak of the season in mid-September could send a system our way.

The strengthening El Niño could eventually act as a kill switch for tropical systems as its atmospheric impacts – including increased wind shear across the Atlantic – kick in, but it would also favor wetter weather for us by late fall or winter.

While it’s dry now and getting even drier by the day in some areas, knowing the when-it-rains-it-pours nature of our precipitation at this time of year, our current flash drought could be over in… well, a flash.

- Categories: