Scarce Showers in April Help Dryness Develop

A month of up-and-down temperatures also saw limited precipitation across the state. Plus, we review an eventful tropical off-season and preview the upcoming hurricane season.

Big Temperature Swings

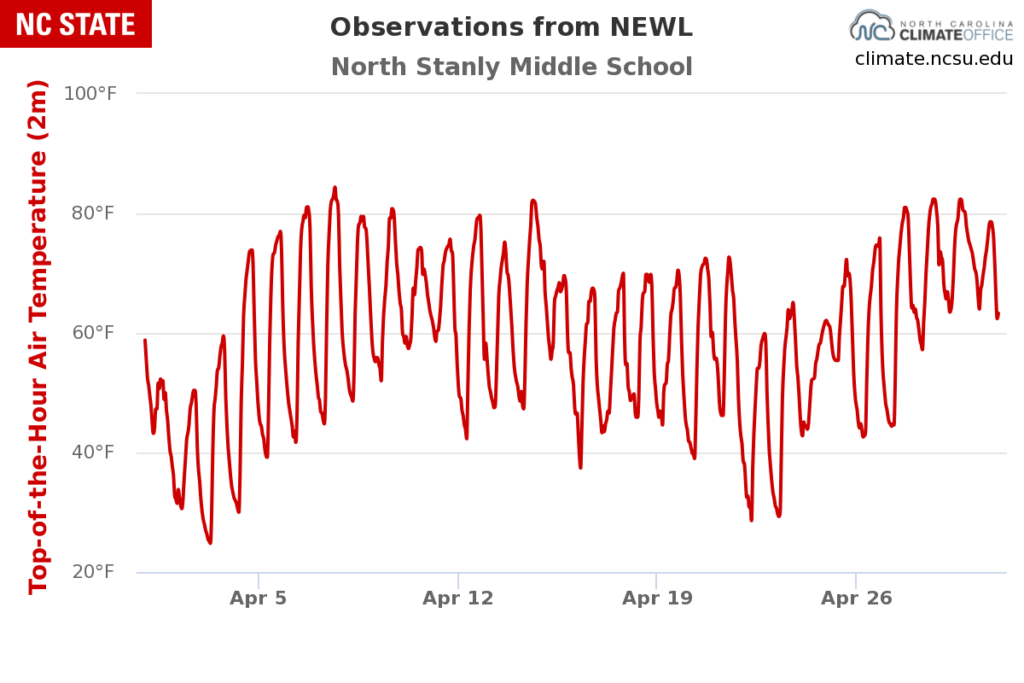

The spring often sees a tug-of-war between the still-cold air to our north and warming tropical air to our south. Last month, their battleground was across North Carolina, as April was a month defined more by our temperature swings and extremes than by the monthly average temperature itself.

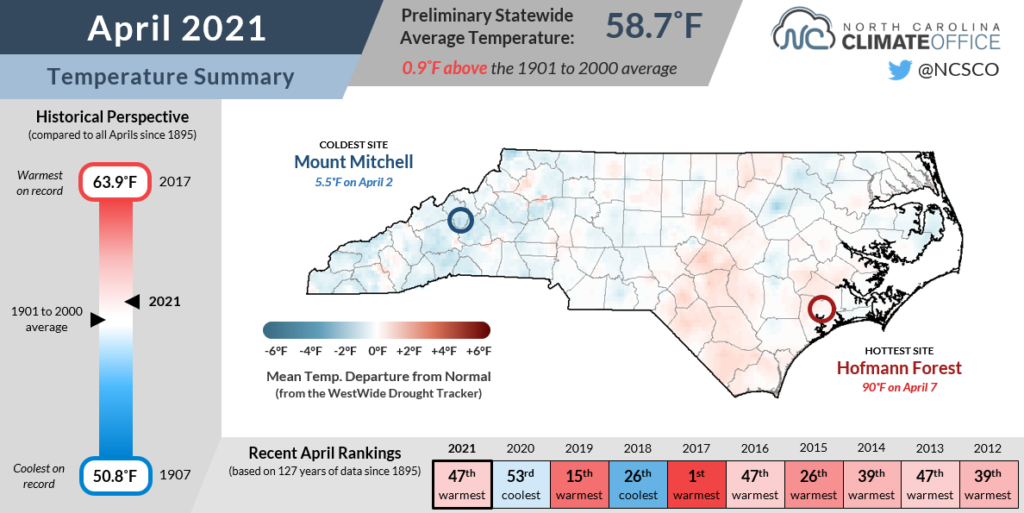

With that in mind, the preliminary statistics from the National Centers for Environmental Information indicate a statewide average temperature of 58.7°F, or tied for our 47th-warmest April out of the past 127 years.

The month started with a chilly morning on April 3, but as we entered a stretch of a warm weather in the week after that — including the state’s lone 90°F reading on April 7 at Hofmann Forest in Onslow County — it appeared we had seen our final spring freeze, not far from the typical timing.

By the middle of the month, regular cold frontal passages presaged more seasonable temperatures, like the April 15 event that wasn’t too taxing, with highs in the upper 60s and low 70s for several days afterwards, as observed at our New London ECONet station.

However, the winter-like chill to our north made one final push behind a cold frontal passage on April 21. With temperatures in the upper 20s to low 30s the following two mornings, that widespread frost or freeze dealt farmers a setback, delaying some tobacco planting and damaging fruit crops in the northern Mountains.

After those cooler mornings, temperatures were on the rise again, reaching the mid- to upper 80s by the end of the month, although not quite making it into the 90s.

At sites such as New Bern and Lumberton, the average first 90°F day is today — May 4 — while the eastern Piedmont and northern Coastal Plain are a week or two from their typical first 90°F occurrence.

Current forecasts suggest all of those areas could hit 90°F this afternoon, making them timely temperatures in some spots, if not unwelcomed warmth in others.

A Dry Pattern Develops

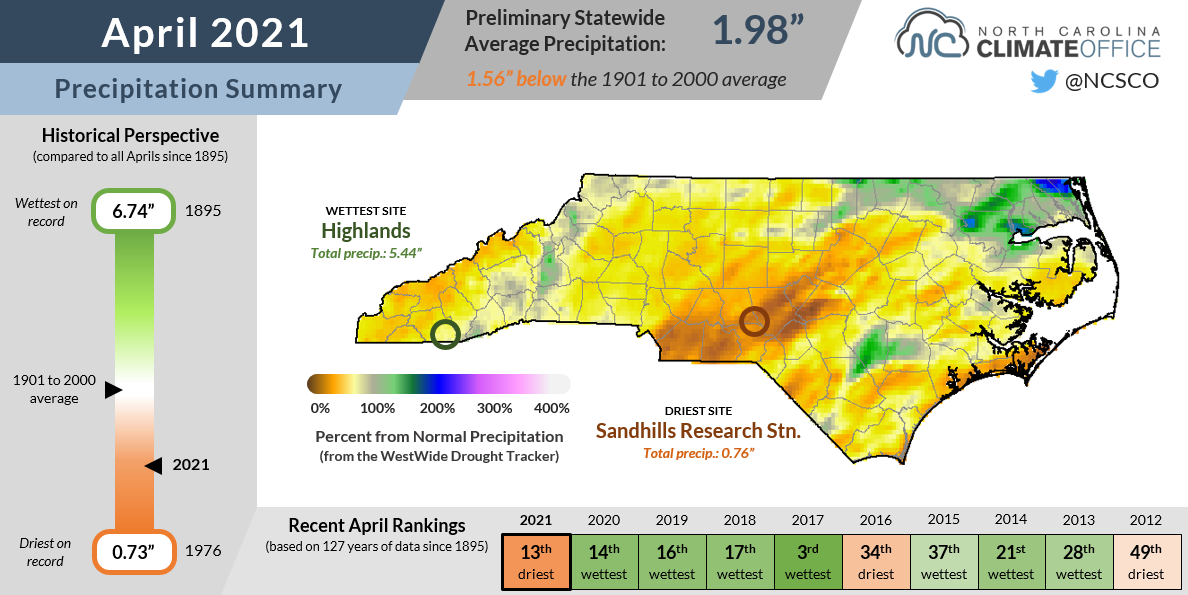

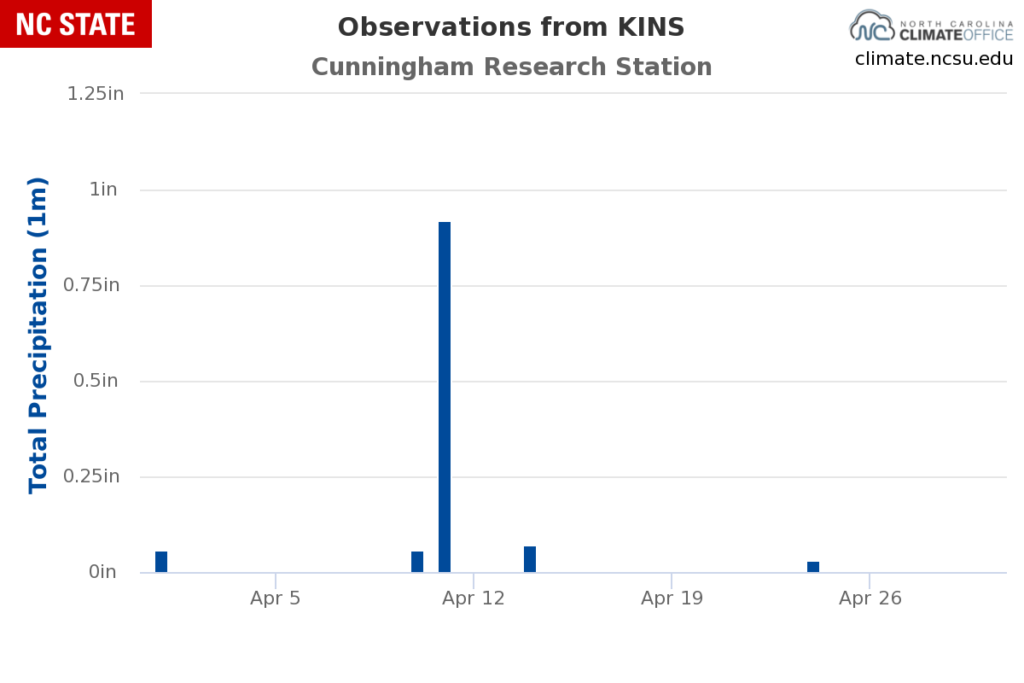

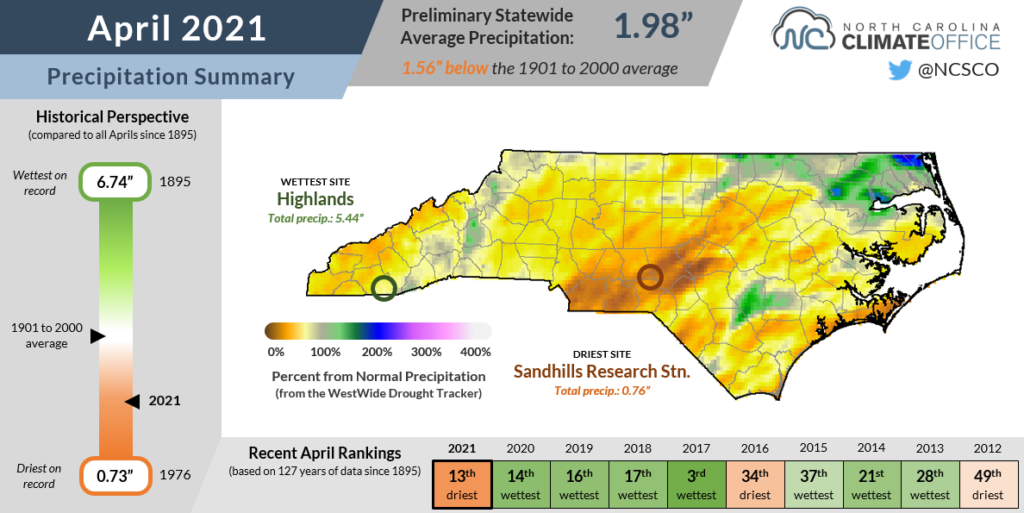

While those cold fronts packed some gusty winds and big temperature contrasts, they didn’t bring much rainfall after crossing the Mountains, which made it an overall dry month. The National Centers for Environmental Information reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 1.98 inches and the 13th-driest April in North Carolina since 1895.

South and east of Raleigh, most areas received less than 2 inches of rain for the month, which is roughly half of their normal April rainfall. Some of the driest spots were along the central coastline, including Ocracoke, which reported just 0.77 inches of rain for its driest April out of 35 years with observations.

The southern Piedmont and Sandhills were the first spots to show signs of dryness, and the region just east of Charlotte has been at a slight precipitation deficit since the start of the year. Last month, Laurinburg reported only 1.32 inches of rain and its 9th-driest April since 1947.

The lone wet spots were confined to parts of the Coastal Plain, and most of that rain fell early in the month. For instance, Edenton had 3.35 inches of rain, tied for its 59th-wettest April out of the past 119 years. However, most of that came from events on April 1 (1.20 inches) and April 10 (1.27 inches).

Rainfall was especially limited in the final two weeks of the month, and as a result, Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions have expanded on the US Drought Monitor to cover about half of the state. At this point, the main impacts have been steadily declining streamflows and topsoil moisture levels.

We’re not yet experiencing drought conditions, thanks in part to our wet winter that raised groundwater levels and saturated the subsoil. But with warming temperatures, increased evaporation, and our precipitation becoming increasingly scattered, parts of the state could see drought impacts as soon as this month.

A Newsworthy Hurricane Off-Season

After being battered by the remnants of at least half a dozen tropical storms last fall, it may be hard to believe that we ever dried out from all that rain — or that the next hurricane season begins in less than a month!

The record-breaking 2020 season, which included 30 named storms in the Atlantic, had ripple effects through the offseason, beginning with an update to the 30-year averages for tropical activity.

Driven by the recent stormy seasons including 2020, the bar for an “average” year now stands at 14 tropical storms and 7 hurricanes, per the National Weather Service. That’s up from 12 named storms and 6 hurricanes under the 1981-2010 normals.

Our most prolific years of 2020 and 2005 each exhausted the initial list of 21 names, and the Greek alphabet was used as a backup plan. That’s no longer the case going forward, as the World Meteorological Organization announced during its March meeting. Instead, a second supplemental list of names — from A (Adria) to W (Will) — will be used in order as necessary, and if any of those storms are particularly damaging, their names will be retired and replaced.

The reasoning for this change was largely that the oddity of the Greek alphabet was seen to detract attention from the storms themselves, some of which like Eta and Iota caused extensive damage. After a Category-5 hit to Central America, Eta fueled a heavy rain event across North Carolina in mid-November.

In addition, similar-sounding pronunciation between some of the Greek letters — like Zeta, Eta, and Theta — defeated the purpose of naming storms, which is to make them easily identifiable and clarify communication about them.

Another announcement at that meeting was the retirement of three names from 2020 and one other from 2019: Dorian, which hit North Carolina as a Category-2 hurricane just days after devastating the Bahamas as a Category-5.

The first name up on the 2021 list is Ana, and recent history tells us we may not need to wait until the official start of the season to see it. In each of the past six years, named storms have formed before June 1. Last May, both Arthur and Bertha brought rain to parts of North Carolina.

One of the most common development regions for those pre-season storms is just off the Carolina coast. Stalled frontal boundaries or low pressure systems can marinate over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, often becoming either tropical or subtropical storms.

The forecast team at NC State led by Dr. Lian Xie has issued their forecast for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, calling for 15 to 18 named storms and 7 to 9 hurricanes — an active season even by the standard of the new 30-year normals.

As of late April, sea surface temperatures are above normal across the central Atlantic, but slightly below normal just off our coastline. The ENSO phase is often a key driver in the hurricane outlook, but that is an added element of uncertainty at the moment.

This winter’s La Niña event has finally faded away, and current forecasts suggest neutral conditions persisting through the late summer. Exactly how conditions evolve over the next few months will shape what ENSO — and, potentially, the peak of the fall hurricane season — might look like later this year.

- Categories: