You’d never confuse them for the rapid-filled rivers snaking through our Mountains, but the flat, straight rivers of the North Carolina Coastal Plain also have a tumultuous history and an occasional angry streak, turning into raging and flooding torrents during our worst storms.

Alongside these rivers, and next to our turbulent ocean, are delicate wetlands that give birth to new life, from rare venus fly traps and seabeach amaranth to various fish species that go on to populate the rivers and the sea.

The balance between these hydrological havens and the wild waters surrounding them is a careful one, and in eastern North Carolina, it’s now being thrown off by broader environmental changes due to human impacts on the climate and land surface.

In today’s post about our curious coast, we venture down the rivers and into the wetlands of the Coastal Plain to explore what makes them special – and what is changing at and beneath the surface.

Our Major Rivers

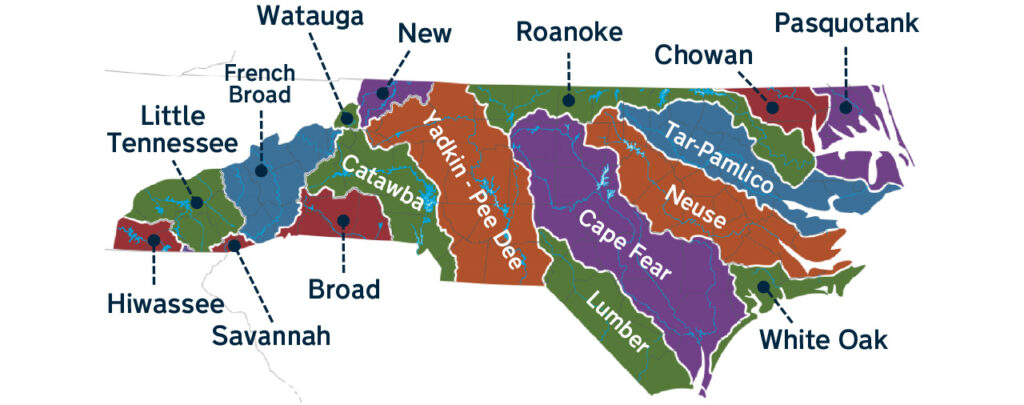

Compared to parts of the central and western United States, where a single river and its tributaries can span entire states, the Coastal Plain of North Carolina stands out for its orderly series of rivers, each flowing from their inland headwaters down to our sounds and ocean.

Among them is the Cape Fear, which runs through Fayetteville and Wilmington before emptying into the Atlantic at its namesake landform – so called because of the fear of a shipwreck that it imbued in the crew of Sir Richard Grenville’s 1585 expedition up the coast.

There are also the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico river basins, each contained entirely within North Carolina. On the banks of these rivers emerged some of our earliest cities and trading hubs, including New Bern, Tarboro, and Raleigh.

Our smaller rivers are no less culturally important. The Lumbee River has been the home of Indigenous people for more than 1,000 years, while the Chowan River and its diverse fish stocks historically sustained a pair of Indigenous Tribes: the Weapemeoc on its west shore and the Chowanoke to the east.

Of course, the history of our rivers goes far beyond even our oldest human civilizations. As we have already highlighted, our coastline once reached all the way to the present-day fall line near Interstate 95 when sea levels were highest almost three million years ago.

As our Coastal Plain emerged from the ocean, rivers began forming shortly thereafter. Geologists have found evidence of five separate terraces – the flat remnants of ancient floodplains – of the Cape Fear River dating back as far as 2.75 million years ago.

These researchers found that the Cape Fear has shifted southward, mainly due to tectonic uplift across southeastern North Carolina.

Climate has also played an important role in the evolution of our rivers, according to Dr. Mike Benedetti, a professor of geography at UNC Wilmington, and Dr. Shannon Klotsko, assistant professor of geology at UNC Wilmington.

They noted that our rivers are currently classified as meandering, or characterized by steady streamflow rates and wide floodplains. But in the prehistoric past, our rivers were braided, or flashier and capable of carrying a greater quantity and velocity of water and sediment downstream, and thus subject to greater erosion and more rapid shifts of their channels.

These braided river processes of North Carolina’s ancient past placed rivers in dramatically different positions compared to where we find them today.

“Where we live in Wilmington, we would have had rivers cutting through there,” said Klotsko.

Based on carbon dating and luminescence dating of sediments, Benedetti said we know the transition from braided to meandering rivers happened near the end of the Last Glacial Maximum around 14,000 years ago, as we settled into our current humid climate with roughly evenly distributed seasonal precipitation.

These well-behaved modern rivers have helped support human civilization and replenish the plentiful freshwater features across the Coastal Plain.

Coastal Water Supplies

When we think about water supplies, especially in the Piedmont of North Carolina, our large reservoirs – including Lake Norman, which supplies Charlotte, and Falls Lake, which supplies Raleigh – may come to mind.

However, these human-made lakes have been around for less than a century. Prior to that, drinking water came from rivers, streams, and groundwater wells. And across the Coastal Plain, that’s still largely the case.

Due to its flat terrain, damming a river to create a reservoir almost anywhere in eastern North Carolina would be an exercise in futility – and almost certainly fatality, given the extent of land it would flood. Coastal communities therefore have few options but to use the handful of natural freshwater sources available to them.

In some places, that means pulling water directly from the rivers. Since 1974, when its current water treatment plant was completed, Goldsboro has gotten its drinking water from the Neuse River. Likewise, Rocky Mount has its water supply in the Tar River, including the Tar River Reservoir – one of the few human-made reservoirs in the region, constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1971.

Wilmington gets its drinking water partially from the Cape Fear River, but also from a pair of aquifers, or pockets of water trapped amid underground rocks and soils. And in Elizabeth City, without access to any sizable nearby rivers, the water supply is drawn from the Yorktown Aquifer, part of the low-lying wetland environment in the northeastern corner of the state.

Relying solely on those sources to supply the entire region can be challenging, especially with more people living there than ever before. The 41 counties in North Carolina’s Coastal Plain have nearly doubled in population since 1970, from 1.6 million to 2.8 million people as of the 2020 census.

During times of drought, our often-ephemeral Coastal Plain freshwater sources can run low. In the fall of 2007, Wilmington imposed mandatory water use restrictions as the Cape Fear River fell to just 4 or 5 inches above the intake in Bladen County. If it fell below that level, the city would have only had around a 30-day supply remaining from that source.

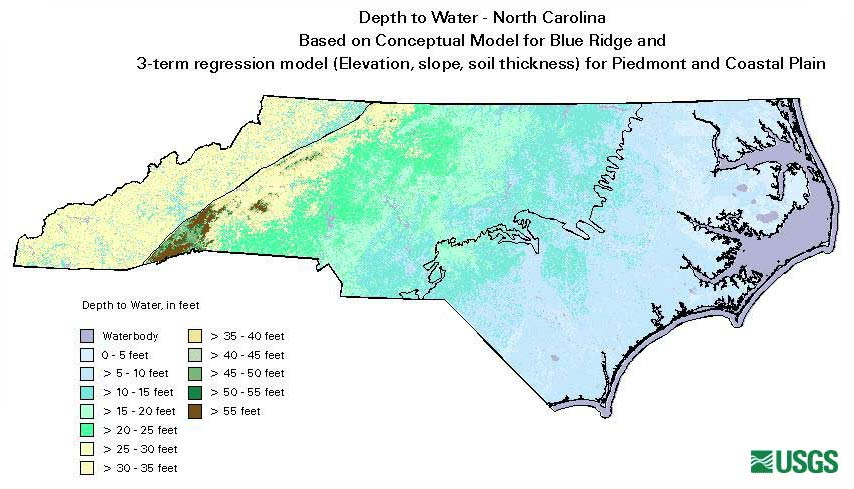

For areas that rely solely on groundwater, they don’t have to dig too deep to access it. Benedetti said the water table is typically only 6 to 10 feet beneath the surface across most of the Coastal Plain. However, that level also varies considerably throughout the year and during times of drought.

“It’s notable for having big fluctuations in depth from season to season due to the warm climate, seasonal changes in temperature, water use by plants, and the sandy soil texture that allows evaporation and infiltration to happen rapidly,” he said.

The water table tends to be deepest at the southern coast and shallowest in the north, where it also contains more organic matter and may appear yellow or brown in color, even after treatment that makes it safe to drink.

It’s in those organic-rich wetland areas close to the coast, including in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuarine system, where freshwater and saltwater mix. Due to their different densities, the freshwater floats on top, forming what geologists call a freshwater lens. In unincorporated rural areas, private wells often tap into this lens as a water supply.

However, this freshwater is fleeting due to the infiltration of saltwater driven by rising sea levels. This saltwater intrusion is pushing the freshwater lens farther inland and overtaking coastal wetland environments – some of which are unique to North Carolina.

A Variety of Beneficial Wetlands

Dr. Marcelo Ardón is an associate professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State University and an expert on our state’s wetlands, which are primarily concentrated in the Coastal Plain.

When you think of wetlands, you might picture bogs or swamps – soggy, shadowy areas where trees draped in moss emerge from the still water and tower overhead. But our wetlands are much more varied than those scenes straight out of Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Ardón speaks with intrigue about Carolina bays, the mysterious round depressions that have formed lakes across parts of the Coastal Plain.

“Once you see them on a North Carolina map, you can’t not see them,” he said. “They’re all over the place.”

Then there are the pocosins, or shrubby bog wetlands typically located at higher elevations near the headwaters of coastal streams. Pocosins are fed by rainfall and topped with several feet of peat soil that has accumulated over thousands of years.

Because of the decomposing organic matter in the soil, pocosins tend to store a lot of carbon, although in cases such as drought events, they can oxidize and release this carbon back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, one of the primary greenhouse gasses responsible for climate change.

“When there’s drought, there is more likely to be fire in these ecosystems, and with fire in these peat soils, you end up losing a lot of carbon and emitting a lot of carbon,” said Ardón.

Fires burning in these organic soils can also be difficult to contain, and they sometimes smolder for weeks or months. That’s why they’re the sources of North Carolina’s largest and longest-lived historical wildfires.

There are also wetlands in areas you might not expect – such as cities. Riparian wetlands along rivers and streams have been encroached on by urban development, but they offer important benefits such as being a buffer for flood waters and improving water quality. That’s why some cities in North Carolina like Jacksonville have prioritized restoring them.

Ardón said that’s just one of many reasons to appreciate our wetlands.

“In general, these coastal wetlands tend to be important and unique because they provide a habitat for lots of different species, they give us flood protection, they sequester a lot of carbon,” he said.

However, some of our wetlands are disappearing, and their names and the scenes taking place within them truly do evoke memories of a horror movie.

They’re called ghost forests, and they’re becoming increasingly common across the Coastal Plain as estuaries and other forested wetlands are now being overtaken by water, killing the trees within them.

“It seems to be a combination of increased saltwater intrusion in some areas, and increased groundwater levels,” explained Ardón, noting that increased salinity makes it hard for trees to take up water, making them die of thirst. On the other hand, rising groundwater levels starve the roots of oxygen.

As they die, they lose their branches, the canopy opens up, and new vegetation develops within them, so it transitions from a forested wetland to a marsh wetland.

While they also provide ecological benefits, such as habitats for birds and spawning grounds for fish, the marshes are not always sticking around.

“In some cases, the change seems to be happening so fast that the marshes never get established, so the forested wetlands get swallowed by the sound or the ocean,” said Ardón.

That underscores the vulnerability of North Carolina’s wetlands within our present and future climate.

New Threats to Wetlands

The sort of “weather whiplash” we saw in 2021 – sudden swings between wet and dry periods – doesn’t bode well for our wetlands.

Ardón noted that studies using remotely sensed observations showed that ghost forests tend to form when drought periods are followed by hurricanes, like we saw in the mid-1990s, 2007-08, and 2011-12. We expect to see more of those back-to-back dry-to-wet events in the future.

“The double-whammy of these two types of events happening together is a good indication of when we will have an increase in ghost forests,” he said.

Hurricanes can wipe out wetlands with their flooding rain and high winds, and that’s also unlikely to improve.

“Storms are increasing in magnitude, so when we have those stronger storms, we can lose some of these ecosystems,” Ardón added.

That’s especially important because these wetlands offer a level of storm protection. Whether they’re along the coastline or next to a river in a major city, they can store excess water and reduce downstream discharge rates during flood events.

Because of that, and following the recent floods from Floyd, Matthew, and Florence, Ardón hopes that interest will increase in restoring wetlands and other natural working lands so their benefits aren’t lost for future generations.

The lower Cape Fear Valley including Wilmington is already surrounded by low-lying swampland, such as Green Swamp to the east and Holly Shelter to the west. Due to sea level rise and saltwater intrusion, more of that land is at risk of befalling a similar fate.

“If all of that gets converted into salt marsh or open water, Wilmington will begin to look a lot more like a peninsula than a coastal cape,” said Benedetti.

Climate changes are also affecting the functionality of our rivers – and could eventually revert them to their prehistoric nature.

As our precipitation becomes more extreme, with heavier rain falling in fewer events and longer dry spells in between, our rivers are seeing greater water and sediment loading, which generates more erosion and could cause them to shift from their stable, meandering variety back to a more volatile braided behavior.

“As the system becomes more flashy and you see more flood events and periods of extreme drought, the river systems will be less stable and less hospitable for aquatic species,” said Benedetti.

Our geological history suggests our rivers are rarely permanent, even during stable periods. Klotsko’s research uses seismic surveys to detect features such as ancient riverbeds, and it shows that heavy rain from a single storm could be enough to open a new channel and eventually force a river to change its location.

That may not happen in our lifetime, she said, but it should make people who live along our coastal rivers consider their risk level when those flooding storms move through.

“I doubt we’ll see a major river avulsion in the next 50 years, but meandering rivers naturally migrate and move in different directions,” said Klotsko. “Living in a floodplain or close to a floodplain is never a good idea, and we have built a lot of artificial structures in them.”

These potential changes to rivers and wetlands are another reminder of a point this blog series has repeatedly realized: the very water running throughout our Coastal Plain that has made this region habitable now threatens to overtake all we’ve built and all we love about the region.

As tomorrow’s final post in this series will detail, with some thoughtful planning and realistic actions to mitigate against and prepare for the changes we’re seeing, we and our communities can still hope to avoid the ghostly fate of some of our coastal wetlands.