Rapid Reaction: Drought Returns to NC Mountains

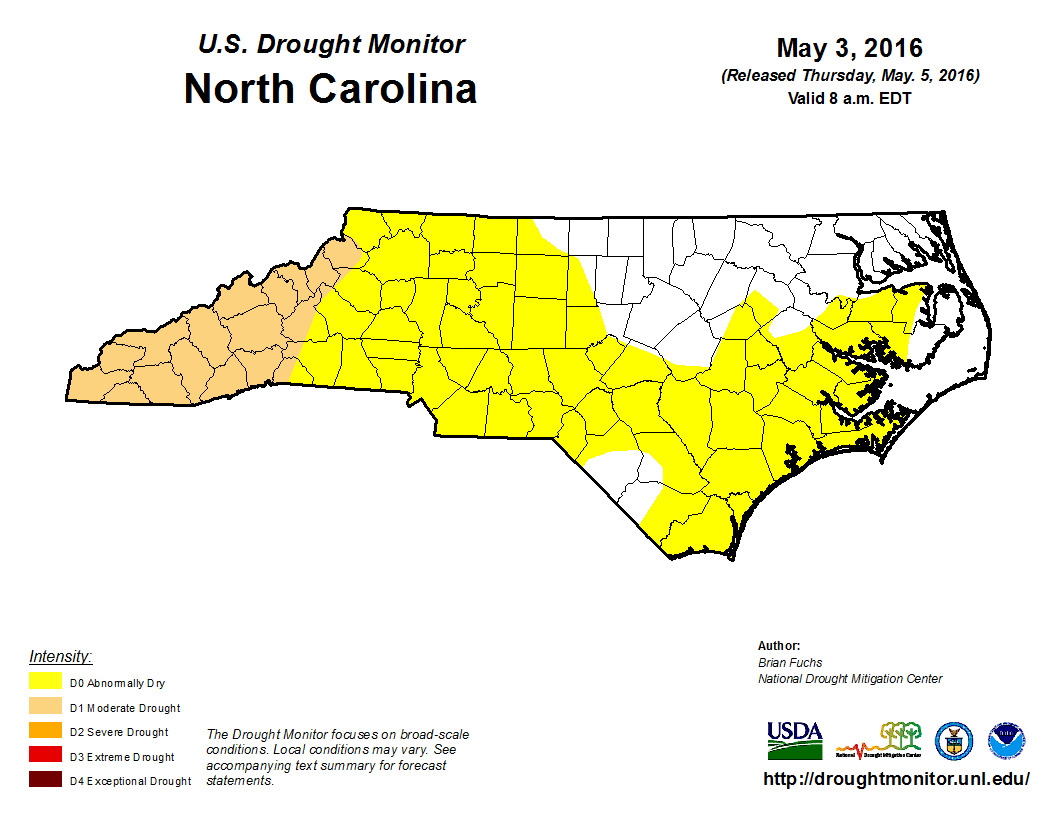

The US Drought Monitor, with input from the North Carolina Drought Management Advisory Council, has re-introduced drought conditions to far western parts of the state in this week’s map. If the emergence of drought in this region seems familiar, that’s because we saw similar Moderate Drought (D1) conditions — least intense drought category on the Drought Monitor’s four-tiered scale — emerge there in the spring of 2007 and in June of 2015.

How Did We Get Here?

Last year’s drought was done in by the onset of El Niño conditions, which brought us a wet fall and winter. However, those El Niño conditions began to weaken this spring at about the same time our temperatures rose and plants started to leaf out across the majority of the state. March in North Carolina finished as the 4th warmest and 7th driest on record, and most of April followed suit.

The western part of the state typically receives about 8 inches of rainfall for the March 1 – May 3 period, the spring season-to-date. This spring, most stations in this region have only received about 4-5 inches. That’s even considering the rains over the last week, which have totaled 2+ inches in many places in western North Carolina. Combine this with temperatures that have been on average 3 to 4 degrees warmer than normal for the spring season so far and it’s not a huge surprise that the state has seen a rapid expansion of Abnormally Dry conditions and the development of Moderate Drought.

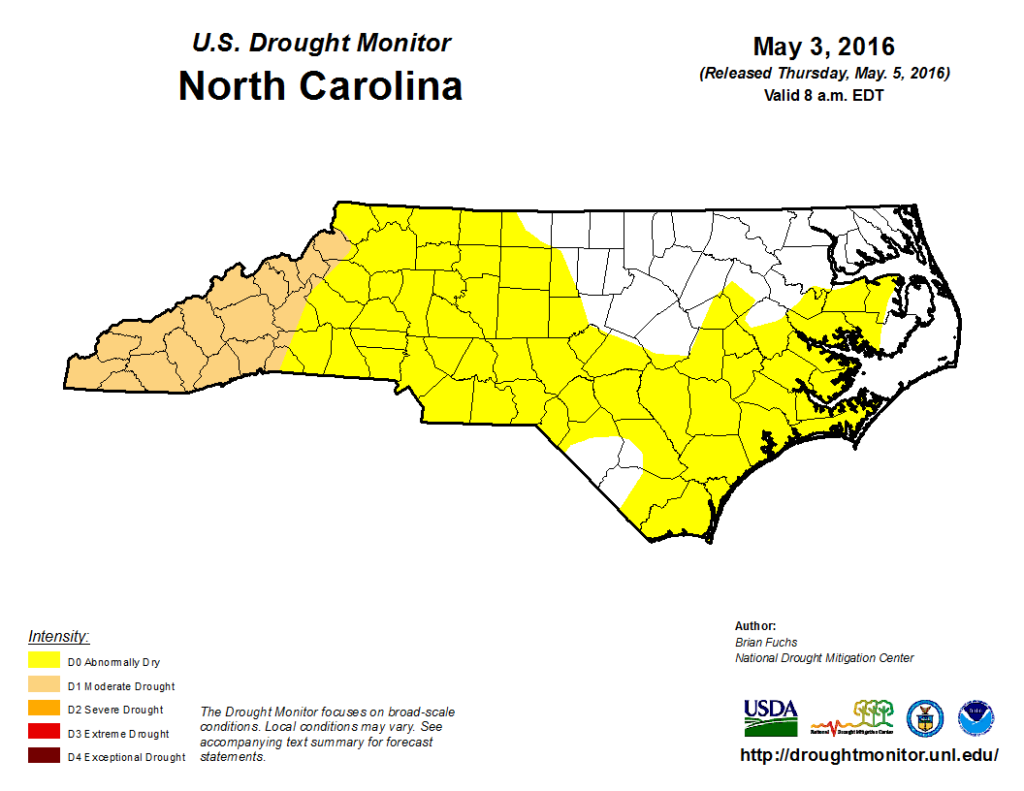

While western North Carolina has experienced the brunt of these conditions, the eastern part of the state hasn’t been spared either. Central and eastern NC have also been about 3 degrees warmer for the season, and there are still some deficits in precipitation that generally increase as you move from east to west. Rains have been more frequent in these areas, however, and that’s led to a reduction in Abnormally Dry conditions over the Albemarle Peninsula and parts of the Triangle.

Crossing the Threshold

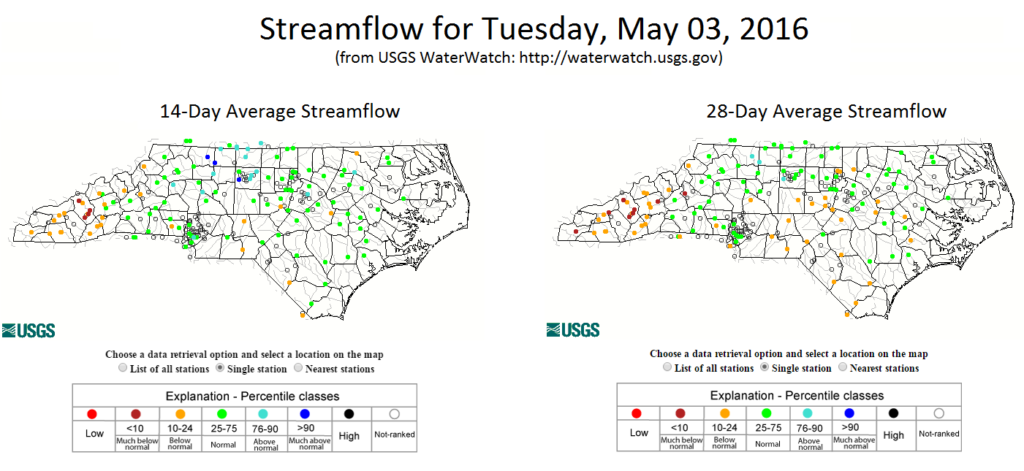

So what’s put the western part of the state over the proverbial edge? The dry, warm start to spring has meant more evapotranspiration — the combination of evaporation from soil and bodies of water plus transpiration from plants — and less precipitation to replenish water sources. This is also happening during a time of year when plants, animals, agriculture, and the atmosphere are all starting to demand more water.

Each week, a team of experts from the NC Drought Management Advisory Council meet to discuss conditions across the state. The emerging dryness has been noted in the weeks preceding this one, but it wasn’t until this past week that evidence indicated a shift in conditions from Abnormally Dry to Moderate Drought across the westernmost 13% of North Carolina, including Asheville, Boone, and Hendersonville. This evidence is based on temperature and precipitation data, drought indices, and on-the-ground impacts, such as streamflow or groundwater levels.

You might also be wondering why drought is now showing up on a map when it rained last week, perhaps even more recently than that. The US Drought Monitor depicts conditions as of 8am EDT on Tuesday, which means that only data prior to this time are included in the weekly update. Impacts from any rainfall or temperatures we’ve experienced since then will be included in next week’s map.

Additionally, although some locations received two week’s worth of rain in a one-week period, that wasn’t enough to make up for the deficits that accumulated over the preceding two months. In Asheville, for example, the airport received 1.97 inches of rain in the past week. However, with only 4.8 inches of total rain since March 1, they are 2.71 inches short of their normal spring precipitation.

Is This Going to be Another 2007 Drought?

The worst drought to affect North Carolina in recent memory began in 2007 and lasted for about two years. While we don’t know yet how this drought will compare, there are some striking similarities between 2007 and now. First, both years were preceded by a wet fall and winter brought on by El Niños. February and March 2007 were both dry and warm, leading to rapidly expanding dryness across the state. This year could almost be a one-month offset of that: a warm, wet fall and winter followed by warm dry conditions in March and April.

Summer 2007 was a sizzler for NC — the 4th driest on record — and by the end of August, over 60% of the state was in Extreme Drought (D3) conditions. While it’s difficult to predict what our summer weather patterns will be because the influence from large climate patterns are weaker, the latest outlooks from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center anticipate seeing above-normal temperatures for the late spring and summer to mid-fall time period.

They’re additionally anticipating slightly above-normal precipitation into early summer over most of southern NC, followed by no real guidance over the remainder of summer into fall. Although they are also anticipating the likelihood of above-normal precipitation into early summer, our spring and summertime precipitation often comes from thunderstorms. As we’ve already seen across the state this spring, these can have very localized impacts, drenching some areas while leaving their neighbors high and dry.

Drought conditions in summer 2007 continued to deteriorate slowly into fall when La Niña developed. When La Niña is present in the winter, North Carolina typically experiences warmer temperatures and less precipitation, and winter 2007-2008 was no exception. The drought bottomed out in December 2007, when almost two-thirds of the state was in Exceptional Drought (D4) — the worst drought category — for three consecutive weeks. While the latest forecasts are also indicating we could see La Niña conditions develop this winter, it’s too early know whether this will impact any possible drought development or expansion.

So, while there are certainly some similarities with the 2007 drought, it’s important to not get too far ahead of ourselves. If the similarities continue and drought worsens in the state, we may need to draw on lessons we learned nearly a decade ago.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We’ve seen droughts in the past, and we’ll see them again in the future. In fact, we’re actively working on tools and research projects to help visualize the historical frequency and spatial extent of droughts — some examples include a new Drought Frequencies page (coming soon!) and our Integrated Water Portal. While droughts can have devastating impacts, they differ from other climate hazards in that they are slow moving. We’re unlikely to see conditions degrade overnight, and we should be able to adapt as conditions change. But the fact that drought is slow moving means that if you aren’t being directly impacted by it, you might just forget it’s happening. So consider this your wake-up call!

This is also a time of year where our precipitation starts to become more convective, which means you just might luck out and receive ample precipitation throughout the summer. However your neighbor down the road, or, worse, the reservoir where you get your drinking water, may not be so lucky, so it’s important to be informed about not only what’s happening in your backyard but also in the areas around you.

If you’d like to report drought (or lack-thereof) conditions in your area, there’s a mechanism for that in the Drought Impact Reporter. CoCoRaHS reporters, who submit daily rainfall observations, can also submit reports of drought conditions. Accurate, on-the-ground information is vital to correctly determining where and how dry things are, and these reports can go a long way towards filling in the gaps.

- Categories: