NC Extremes: Arctic Air Masses Pack a High-Pressure Punch

This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

When it comes to moving the mercury in barometers up to record-setting levels, nothing does the trick quite like a wintertime Arctic high pressure system. But before we get to North Carolina’s high pressure records, let’s briefly review air pressure, including how we measure it and how wintertime Arctic highs get so strong.

Pressure Primer

Simply defined, air pressure is the weight of the air above you. As you rise in elevation, there is less air above you and the pressure is lower. This creates some challenges when comparing air pressure measurements at different locations. For example, in Boone — at 3,000 feet above sea level — the typical local barometric pressure, or station pressure, is about 900 millibars. However, you wouldn’t expect to see pressures this low at a low-elevation site like Wilmington unless something like a strong hurricane was moving through.

To account for these elevation-induced differences and make site-to-site comparisons easier, weather stations often report the sea level pressure. This is essentially the pressure a site would experience if it were at sea level, or zero feet in elevation. Under standard atmospheric conditions at sea level, typical pressures are about 14.7 pounds per square inch, or, equivalently, 29.92 inches of mercury or 1013.25 millibars.

Intense Arctic Highs

In the winter, the Arctic receives little to no sunlight, so surface temperatures stay cool. Cold air is denser than warm air, so cold air pooling in one location becomes relatively heavy — and remember, more weight means higher pressure.

With this in mind, it’s no surprise that most global records for the highest recorded air pressure — generally around 1080 mb or about 32 inches of mercury — have been set during the winter in places like Siberia and Canada.

As these Arctic highs move south, they tend to weaken for a few reasons. More southerly locales receive more sunlight, which helps to moderate these air masses. Also, because cold air sinks, these systems tend to be relatively shallow, and as they move over warmer ground, the near-surface air warms and the intensity of the high pressure wanes.

But on occasion, a high pressure system will dive south over cool, snowy ground accompanied by reinforcements from cold upper-level air, setting the stage for high pressure records far from the North Pole.

NC’s Highest Sea Level Pressure

In February 1981, the ingredients for a record high pressure event began to take shape. An active polar jet stream sent a steady succession of strong upper-level lows and shots of cold air southward over the continental United States. On February 9, a surface high-pressure system began to dive south out of western Canada, moving over the snow-covered Rockies.

The high continued to move south, led by a strong cold front that dropped temperatures in Texas from the 60s into the teens. As the front approached North Carolina, warm air poured in from the south and temperatures climbed into the mid-60s in the early morning hours of February 11. The sharp boundary between warm, moist air and cool, dry air fueled showers and thunderstorms just ahead of the cold front.

The front pushed through North Carolina on the afternoon of the 11th, bringing clear skies and dropping temperatures more than 30 degrees in a four or five hour period. Over the next two days, temperatures stayed cold — the highs on February 12 were mainly in the 20s and low 30s.

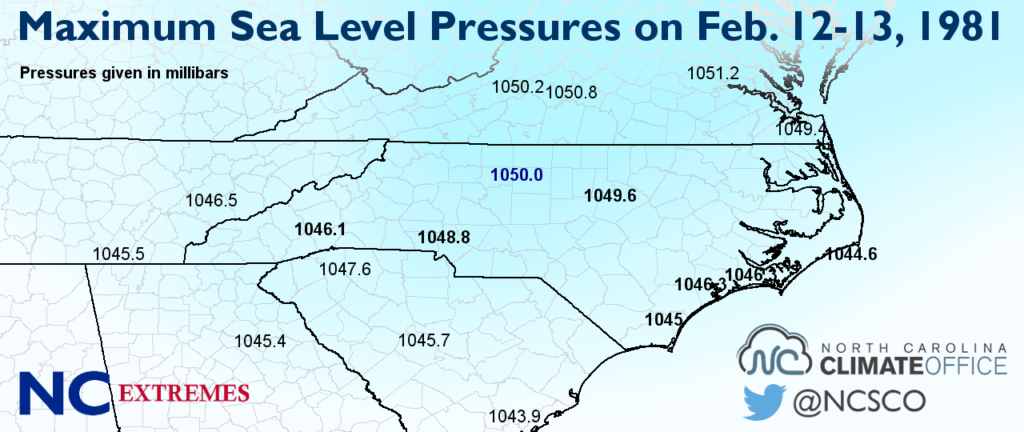

On Friday, February 13, 1981, the heart of the high pressure system passed to our north and caused record high pressure readings of more than 1050 mb in parts of New England. As we often see in cold air damming events, that high to the north funneled cold air down the east coast, trapping it on the east side of the Appalachians.

By mid-morning on 13th, the mercury peaked in barometers across the state. At 10 and 11 am, the sea level pressure readings in Greensboro climbed to a record-setting 1050 mb, or 31.01 inches of mercury. Around the same time, Raleigh hit 1049.6 mb and Charlotte climbed to 1048.8 mb.

As the high pushed offshore, warmer weather returned over the next few days and the pressure decreased from its all-time high value.

Other High Pressure Events

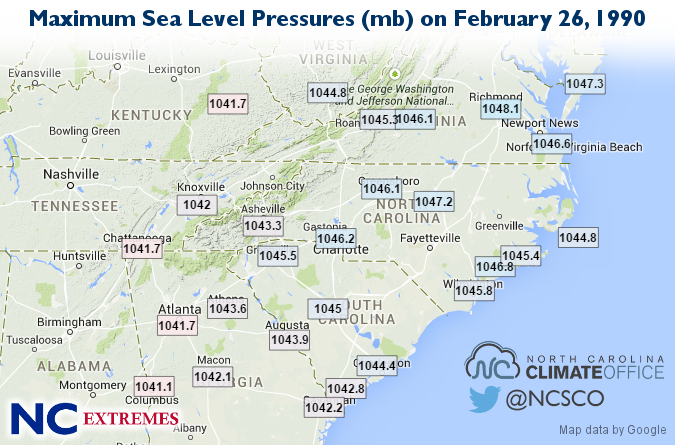

Nine years after the 1981 event, in February 1990, another Arctic high dropped out of central Canada, tracked from the Upper Midwest to the Northeast, and delivered a similar cold air damming setup across North Carolina. Sea level pressure values peaked as high as 1047.2 mb in Raleigh with values exceeding 1045 mb along the coast.

Since these coastal stations are at low elevation, their station pressures were almost equally high. At the New River Marine Corps Air Station in Jacksonville, the station pressures (left) rose as high as 1045.6 mb at 10 and 11 am on February 26. That’s the highest station pressure value we found for North Carolina in the historical records.

More recently, we saw several high pressure events in January 2008. On January 3, a surface high was parked on the west side of the Appalachians, and several high-elevation stations had estimated sea level pressure values approaching 1050 mb. Later that month on January 21, a strong high just to our north again had the mercury rising, with statewide sea level pressures exceeding 1040 mb.

So the next time a blast of cold, dry air pours in, don’t just keep an eye on the thermometer. Take a look at the barometer as well to see how high the pressure climbs.

- Categories: