Arctic Air Invades in December, But Was It Too Cold for Snow?

This month’s climate summary highlights December’s surge of cold weather, ongoing dry conditions, and a new sensor being tested at one of our ECONet stations.

Cold Air Arrives Late in the Month

It was up on the housetop, down through the chimney, and in the air on many silent nights. An Arctic chill made its way to North Carolina, providing a frigid send-off to 2017.

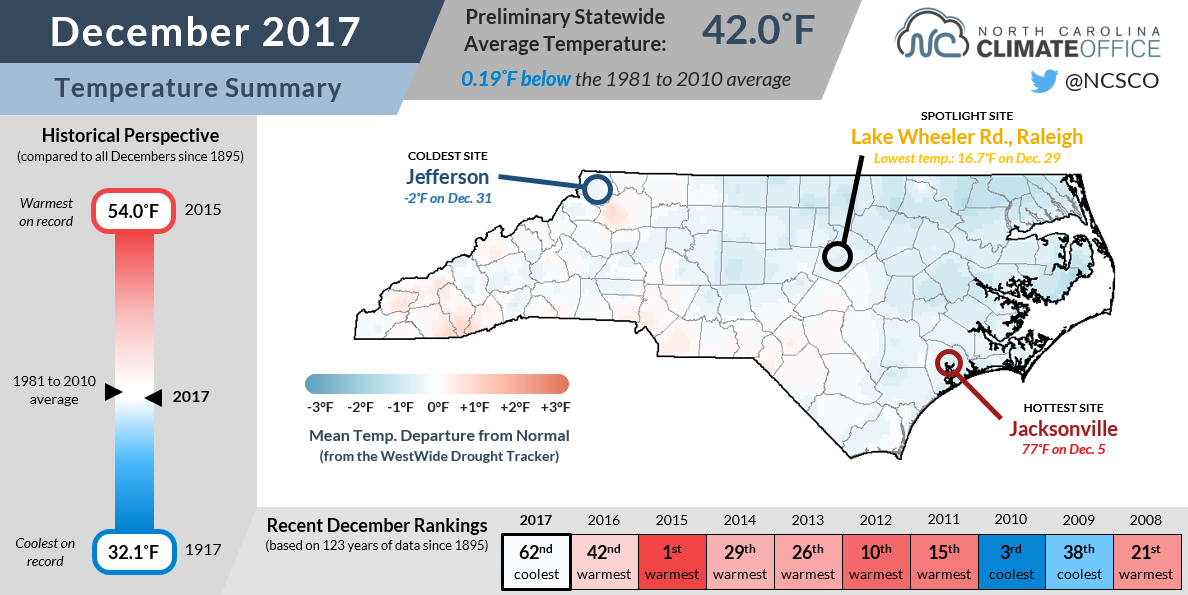

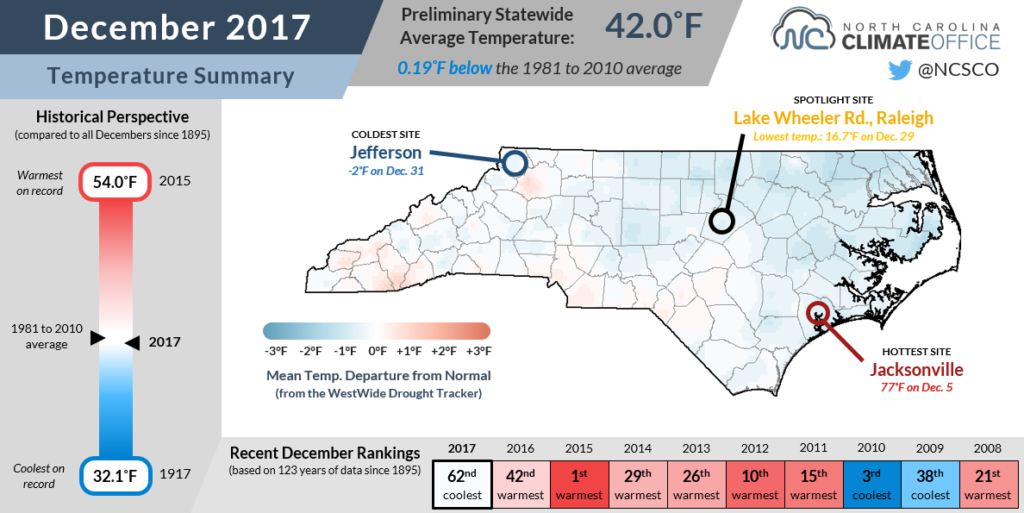

The final week of the year was the 5th-coldest on record in Raleigh dating back to 1944, the 5th-coldest in Statesville since 1902, and the 3rd-coldest in Wilson since 1916. It was a chilly way to wrap up the year, and on the whole, it was our coldest December since 2010.

Given that late-month cold snap, it may surprise you that last month’s statewide average temperature of 42.0°F was just 0.19°F below the recent 30-year average, ranking as our 62nd-coolest December since 1895, positioned right in the middle of the 123 years of record.

It’s easy to forget that early in the month, high temperatures soared into the 70s, peaking at 77°F in Jacksonville on December 5. A separate mid-month warm-up brought a week temperatures up to 20 degrees above normal, which effectively balanced out the recent cold weather to yield our near-normal monthly average temperature.

Of course, we’ll probably remember this December mainly for the intense cold caused by a southward-sinking polar vortex as well as an Arctic air mass over the northern Plains that brought below-normal temperatures to the eastern two-thirds of the country.

The most severe cold showed up just as the month ended. Our weather station on Mount Jefferson hit -2°F in the waning hours of December. That was its coldest temperature of the entire year, and the lowest recorded there since hitting -3.8°F on January 19, 2016.

Dry Weather Continues in the West

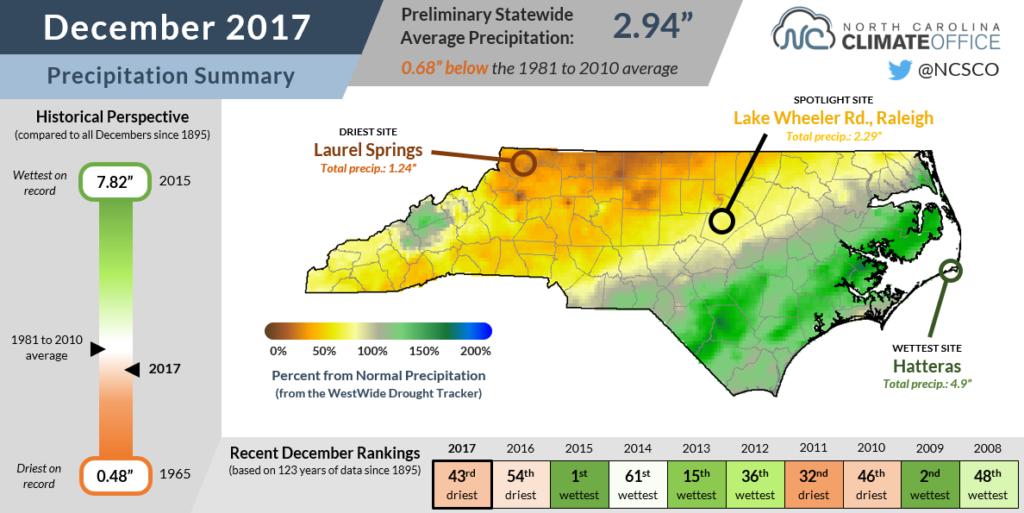

Whether it was warm or cold outside, one common feature of December was a lack of precipitation. The statewide average precipitation of 2.94 inches was 0.68 inches below the 1981 to 2010 average, ranking as the 43rd-driest December on record.

The most significant precipitation event came on December 8-9, with several inches of snow in the western part of the state and several inches of rain in the east. The rainfall from that event helped give the southern and eastern parts of the Coastal Plain above-normal precipitation for the month. That includes Hatteras, which had 4.9 inches of rain in December — 0.6 inches above normal — and Wilmington, where the 4.45 inches of rain was 0.8 inches above normal.

Outside of those wet spots in the Coastal Plain and in parts of Buncombe and Madison counties in the Mountains, most of the state received just 50 to 75% of their normal monthly precipitation. As with the coldest site in the state, December’s driest site was also in Ashe County. Laurel Springs received just 1.24 inches of precipitation all month.

That dry weather resulted in a westward expansion of both Abnormally Dry (D0) and Moderate Drought (D1) conditions into the Foothills and western Piedmont, respectively.

With sufficiently cold air in place for wintry precipitation, that begs the old question: Can it be too cold for snow?

Theoretically speaking, no. Even sub-zero air has a slight amount of moisture in it, so snow crystals could conceivably form and fall in such frigid conditions.

But practically speaking, yes. Our coldest air is usually associated with Arctic air masses like the one that moved in during late December. Those high pressure systems are associated with sinking air — the opposite of the lifting needed to form clouds and saturate the air. In addition, with the polar jet stream sagging far to the south, no storms were able to track up the coast and provide the moisture needed for snow.

As we’ve entered January, though, that pattern may shift for at least a few days. As this post goes to press, forecasts are calling for snow in the eastern part of the state as a storm develops offshore. For coastal locations where all-snow events are uncommon, this may be one event in which it’s actually cold enough for snow.

A New Temperature Take at LAKE

In each of our monthly climate summaries this year, we will highlight a different location across the state with interesting weather, memorable past events, or other notable goings-on. For December, our spotlight site is our Lake Wheeler Road ECONet station in Raleigh.

Located at NC State’s Lake Wheeler Road Field Laboratory, this station is one of the longest-lived in our network, making its first hourly observations in May 1982. The current 10-meter tower was installed in 2001, replacing the older platform-based station.

December at Lake Wheeler followed the statewide trends, ranking as the 11th-coolest and 13th-driest out of its 29 years with data.

Due to its proximity to our office, the Lake Wheeler station is often used for sensor testing and experiments. Last month, we began testing a new downward-facing infrared thermometer, which can provide a measure of the ground temperature.

Although all 40 of our ECONet stations already measure soil temperature, the difference between the ground and soil temperatures may be greater than you’d think.

During last week’s cold snap, for instance, the nighttime air temperature on December 29 dropped to 16.7°F but the soil temperature at a depth of 10 centimeters (4 inches) held steady at 36.3°F. Our new infrared thermometer recorded a minimum temperature of 17.7°F, providing a more accurate representation of conditions at the ground surface.

Both the soil and ground temperature sensors provide useful information, but for different purposes. Farmers often use soil temperature to assess conditions in the root zone, while ground temperature is more useful for gauging whether the surface is cold enough for frozen precipitation to stick.

We plan to evaluate the ground temperature sensor at our Lake Wheeler station throughout the winter, and if the data looks good, we may install those sensors at a handful of other stations in our network. That would provide valuable insight for the National Weather Service, the Department of Transportation, and other groups to know whether snow might stick when wintry weather approaches.

- Categories: