Fire Climatology

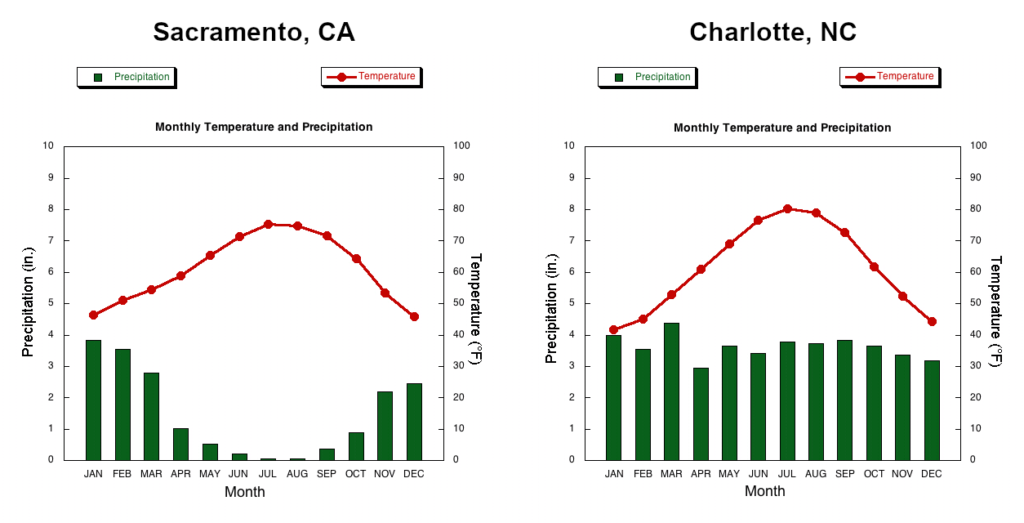

Regions like the western United States stand out as hotspots for wildfires, and for good reason: almost no rain falls there during a pronounced dry season from late spring to early fall, causing vegetation and other fuels to dry out to an extreme extent.

By comparison, precipitation is roughly even across all seasons in North Carolina, thanks to the influence of two nearby bodies of warm water in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. They moderate our overall climate, keeping us warmer in the winter than the continental regions to our north and west, and milder and more humid in the summer than the desert regions at our same latitude across the southwestern US.

Despite this more well-rounded precipitation regime, we do tend to see increased fire activity a few times each year, mainly driven by our temperatures and other environmental factors.

Spring Fire Season

Between mid-March and mid-April, our daytime high temperatures typically begin to climb into the 70s, and after the spring equinox, our days become longer than our nights. The increased intensity and duration of that solar radiation can more easily dry out surface fuels and vegetation. In addition, before trees have fully greened up in the spring, the sunlight can reach the ground between those bare branches, and the trees themselves effectively become exposed woody biomass that can easily burn.

While our average springtime precipitation is nearly equal to what we see in the winter, our precipitation patterns begin to change by mid- to late spring. Instead of cohesive frontal systems bringing widespread and continuous rainfall across the state, our rain increasingly comes from convective showers and thunderstorms that may drench one area while missing its neighbors a few miles away. This can create dry pockets that consistently miss out on those showers, and when the pop-up storms return to those spots, lightning can increase the risk of fire ignition.

When frontal passages do occur in the spring, they can usher in a dry airmass with gusty winds. Those windy, low-humidity days are ideal for fires to start and spread, whether from natural sources like lightning strikes or human ignition causes such as an act of arson, an unexpected spark, a debris burn gone out of control.

Fall Fire Season

By late September, these same trends from the spring happen again, but in reverse. Our temperatures can remain relatively warm well into October, and once trees drop their leaves, they ramp up the fuel loading at the surface.

As we move into a characteristically crisp and less humid fall weather pattern, those dead leaves are prone to quick ignition, especially on dry and windy days once our cool-season frontal passages begin again.

While our fall fire seasons historically aren’t as active as those in the spring, if overall environmental conditions are drier such as in the fall of 2016, we can have extremely active falls with numerous wildfires across the state.

Drought Events

One wildcard in our wildfire climatology is the presence of drought. During extended dry periods, those usually reliable moisture sources to our south and east can be replaced by persistent warm air masses sitting over the Southeast US, under which we can go without precipitation for days or weeks at a time.

While wildfires are not common during the winter, the emergence of warm weather following a few dry months can see an early start to the spring fire season. Notably, windy weather behind a cold front on February 10, 2008, fanned the flames of more than 300 wildfires across the state, and amid an ongoing drought, more fires ignited that March prior to the typical beginning of the spring fire season.

The risk of rapid ignition tends to decrease after green-up and as those dry, windy days become less common in the late spring. However, evapotranspiration rates remain high during the hot summer months, and it doesn’t take too many rain-free days in a row to dry out soils and surface fuels. This is especially worrisome in the peat soils of eastern North Carolina. If the water table falls and these organic soils dry out, they can burn easily and for prolonged periods of time, such as during the 2011 drought.

That year, and in many of our other summer droughts, the best remedy is often a tropical storm in the late summer or early fall that can bring soaking rains to saturate soils, erode precipitation deficits, and extinguish any ongoing wildfires.