A Warm, Dry March Fans the Fire Season’s Flames

March saw stretches of spring-like weather on either side of a cold week, and generally dry conditions across the state that made for an active start to the spring fire season.

Widespread Warmth, with One Cool Week

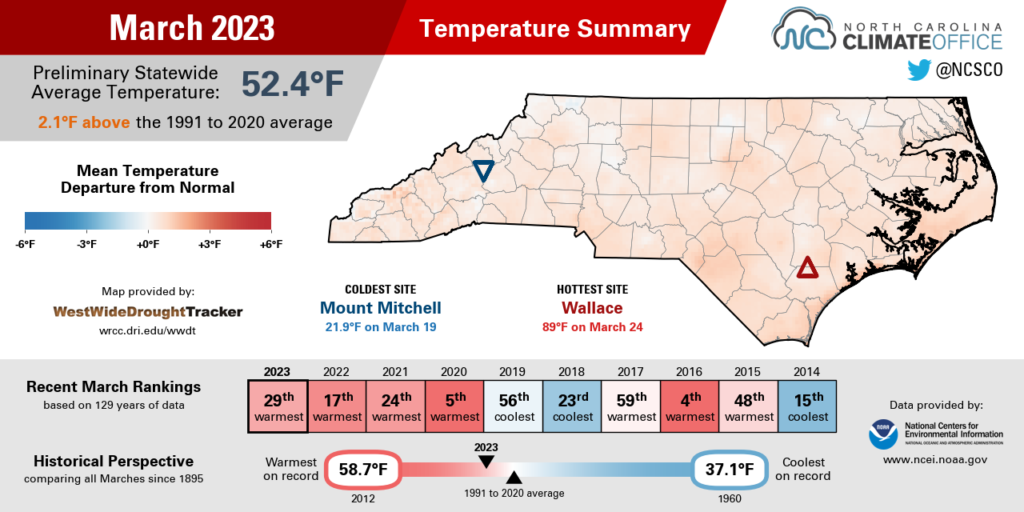

Apart from a mid-month cool snap, spring-like temperatures prevailed in March. Statewide, the average temperature was 52.4°F, which ranked as our 29th-warmest March out of the past 129 years according to preliminary statistics from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

The average temperatures across much of the state were 2 to 4 degrees above normal. In Wilmington, it was tied for the 20th-warmest March on record, while Charlotte tied for its 22nd-warmest March and Raleigh had its 23rd-warmest March dating back to 1887.

Following our record warmth in late February, the first week of March included several days with highs in the 70s at the hands of high pressure over the Carolinas.

Our temperatures then went tumbling after a Canadian air mass moved in. Beginning on the morning of March 14, many Piedmont and coastal areas had sub-freezing temperatures on five of the next seven nights, aided by a reinforcing shot of cold air on March 20.

The chill was widespread, with low temperatures in the 20s on March 21, including in Jacksonville and Elizabeth City, which each dropped to 24°F. Even along the Outer Banks, our ECONet station at Jockey’s Ridge State Park bottomed out at 32°F – the coldest night there in more than a month, since February 19.

Our persistent warmth dating back to February had been a boon for crops and other vegetation, so the week of colder weather in March created some concerns for freeze damage. Hertford County Extension cautioned that any winter wheat that had already jointed – when the lowest node or growth point emerges above the soil surface – was especially vulnerable.

Fortunately for farmers, that freezing weather – all before the typical last spring freeze date, it should be noted – was fleeting, and our temperatures then took a dramatic upswing late in the month.

The warmest afternoon of the year so far was on March 24, with widespread 80s across all three regions of the state. Locally, New Bern (87°F) and Elizabeth City (86°F) set new daily record highs, while Raleigh (87°F) and Fayetteville (86°F) came within one degree of their daily records.

Drought Creeps Back In

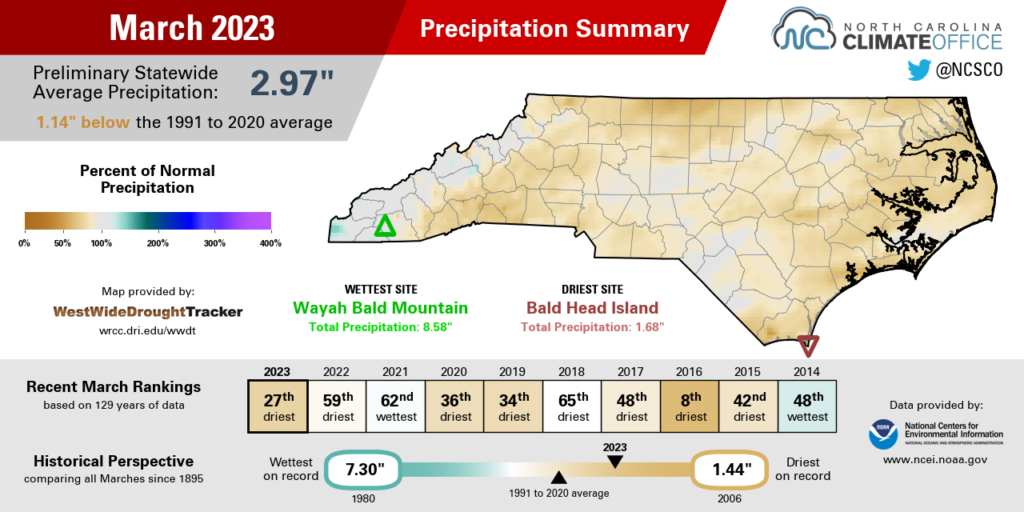

Those warm, sunny days and high-pressure patterns left little room for rainfall last month, so it was a dry March across North Carolina. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 2.97 inches, or our 27th-driest March since 1895.

Unlike last fall, when the west was wet while the coast was dry, the entire state had below-normal precipitation last month as few moisture-loaded weather systems made it across the Appalachians or up our coastline.

In the Mountains, it was tied for the 14th-driest March in Asheville and the 9th-driest at Pisgah Forest. In the Piedmont, it was the 9th-driest March in Hickory and the 24th-driest in Charlotte, with long-term records in the Queen City dating back to 1878. And in the Coastal Plain, it was the 6th-driest March on record in New Bern and tied for the 9th-driest in Elizabeth City.

The Mountains had their heaviest rains earlier in the month, with totals of more than 2 inches during a cold frontal passage on March 2 and 3. After that, drier conditions set in there and elsewhere across the state. Most of our March rain events were light, such as the half-inch to an inch totals on March 12 and 13 associated with a weak low pressure system over the Southeast.

Our precipitation last month also included something frozen – although as with our rainfall, it was light and fairly localized. On March 12, CoCoRaHS observers in the northwest reported up to an inch of snow on the ground in Sparta, with a dusting from Mount Airy through Mocksville. As we noted in our winter recap, it finished as a snow-free season for most of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, and even western sites had just a fraction of their normal snowfall.

The switch to spring included our first days of the season with significant thunderstorm activity late last month. On March 26 and 27, a line of intense storms that produced totals of almost 7 inches in central South Carolina also brought more than 3 inches to Whiteville in Columbus County. That same event included a severe storm with damaging straight-line winds estimated at 60 mph in Brunswick County.

But for the majority of eastern North Carolina, soaking rains remain elusive as we head into the heart of spring. Through the end of March, Wilmington is 2.93 inches below its normal precipitation for the year to date, and the Holly Shelter Game Land in Pender County is 3.33 inches below average so far in 2023.

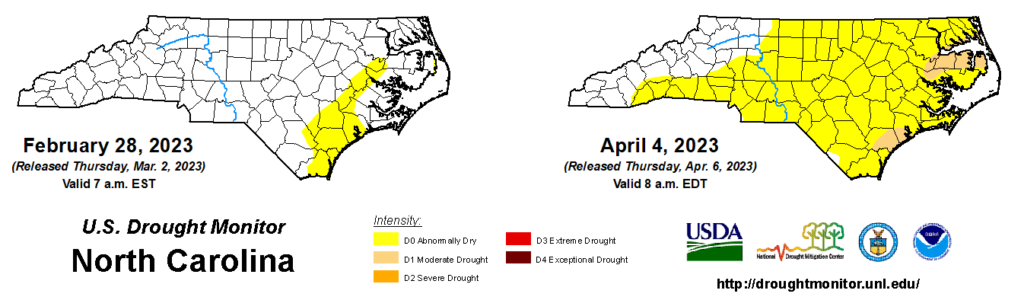

As a result of that ongoing dryness, Moderate Drought (D1) re-emerged across parts of the coastline last month, including along the Albemarle Sound, while Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions expanded into the Piedmont.

Those changes reflect our drier pattern since mid-February and some emerging impacts, such as declining streamflow levels. With help from some April showers, those areas can avoid slipping into drought, but without any rain soon, dryness and drought could take hold across more of the state.

Spring Fire Season Heats Up

The combination of warm and dry weather coming out of the winter and into the spring has made this fire season a busy one so far.

Between January 1 and March 31, the North Carolina Forest Service has noted 1,647 wildfires on state-owned and private lands. That’s the second-most fires up to this point in the last five years, trailing only 2,939 fires in the first three months of 2022.

This tends to be the most active time of year for wildfires for several reasons. As temperatures warm up – sometimes well into the 80s, as we saw last month – moisture quickly evaporates from vegetation and other ground-level litter, such as sticks and branches.

Behind early spring cold fronts, humidity levels can drop and winds can pick up, which also makes environmental conditions suitable for fast-spreading fires. That was the case on March 7, when relative humidity values below 30% and wind gusts of more than 30 mph caused a number of wildfires across the state, including a 3,500-acre brush fire on Camp Lejeune.

Along with those weather factors, fire danger often peaks in the spring before trees have fully leafed out and greened up. At this precarious point during the change of seasons, deciduous trees offer little shade for the forest floor beneath them, all while acting as a ready source of flammable woody biomass themselves. As of the end of March, the Coastal Plain was approaching 50% green-up, which has been both helped by the warmer weather and delayed by the emerging dryness.

Human actions can play a role as well, especially as people get outdoors to burn debris accumulated during the winter. An escaped debris burn was the cause of the largest wildfire in the state last month, which started on private land near the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Tyrrell County on March 24.

Since then, the so-called “Last Resort fire” has burned 5,290 acres and is 68% contained as of April 4. That makes it the 14th-largest fire on state or private lands in the NC Forest Service’s records dating back to 2000, and the largest since the Chestnut Knob fire, which burned more than 6,400 acres in November 2016 as part of that active fall fire season in the Mountains.

As we covered a few years ago, this corner of eastern North Carolina has historically been home to our largest wildfires, and they usually happen during spring or summer drought events. While the water table is typically high in these low-lying wetland areas, the water levels can drop during droughts and expose the heavily organic soils and tree roots, which can burn and smolder for weeks or months at a time.

It usually takes several good rain events or continuous pumping from external sources – and NC Forest Service has pumped in 120 million gallons of water so far along the fire’s perimeter – to contain the fire and tamp down any lingering hot spots.

Since it’s burning in one of the most rural and sparsely populated parts of the state, this fire is not expected to threaten many homes or other structures, but depending on the wind direction, its smoke could reach other areas, especially across the Coastal Plain.

To stay aware of any potential air quality impacts, make sure to check out our Air Quality Portal to see if current or forecasted conditions might be hazardous in your area.

- Categories: